Gradually the Multilingual Person:

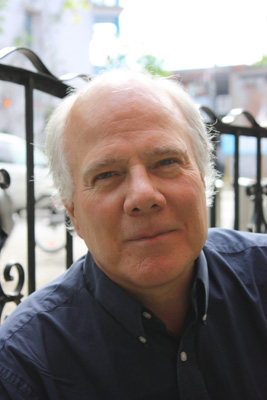

Katia Grubisic In Conversation with Hugh Hazelton

Poet, editor, and translator Katia Grubisic spoke with the award-winning translator and writer Hugh Hazelton about his process and proclivities. Hazelton has authored and edited several books on the literatures of the Americas and is a frequent contributor to translation journals. He taught for many years at Concordia University and is presently co-director of the Banff International Literary Translation Centre. Hazelton has received many prizes and accolades for his work, including the Governor-General’s Literary Award for Translation for his 2006 translation of Joël Des Rosiers’s Vétiver. Of special interest are Hazelton’s remarks about the baroque, inherently impossible act of translation and the “subtle bite” of Zulmira Ribeiro Tavares, whose work in Portuguese appears in his English translations featured in Issue 188: At Home in Translation.

KG: You chose to live in Montreal over four decades ago. Was there something linguistic about the city that drew you? It’s possible, and even frequent, to begin a conversation in one language, and finish in another, or to forget entirely the language in which an interaction or event took place. Is it erasure, or accrual? Do you ever find that the multiple strata and code-shifting complicate linguistic identity, or even language itself? Does the literature of Montreal (in which category I include literary translation) have a particular timbre?

HH: I first arrived in Montreal in 1969. I’d never been in the city before, but had already decided I was going to live here. I’d been a part of the draft resistance movement in the U.S.; they’d reclassified me and were preparing to call me up for service in the Vietnam War, so I’d decided to move to Canada. I’d studied both French and Spanish literature at university and had lived briefly in France, and I thought Montreal would be a great place to settle. When I arrived here, I was immediately drawn to the cultural possibilities of life in a bilingual and bicultural environment and to the fluidity and versatility of Quebec culture, literature, and language, which were bursting with vitality and undergoing a powerful renaissance, as was English Canadian culture. It was the time of Paul Chamberland’s Terre Québec and Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers. All of this was exciting to me, and my first job in Montreal was in French with the Association coopérative d’économie familiale (ACEF), a progressive social-work agency. I later lived in Newfoundland and British Columbia, and felt an attachment to both, but the pleasure of living in a multilingual environment stayed with me, and, after travelling for two years in Latin America, I moved back to Montreal permanently. After my return, I spent much of my time with Spanish-speaking friends, many of whom were exiles from countries that had suffered coups d’état in the 1970s, and gradually began to live within a cultural milieu that involved the three languages. This pattern solidified as I taught English and Spanish in French cégeps and universities; I also began reading my poetry in Spanish and French at bilingual literary events and to move into literary and professional translation from Spanish and French into English. Montreal is a wonderful place to teach translation, since a large proportion of the population is continually translating as they go about their daily life, and students have an extraordinary degree of sensitivity to the intricacies of language.

What’s so enjoyable about Montreal is that you can be constantly shifting languages. I often find myself thinking in English, French, and Spanish within a few minutes’ time, especially as my mind wanders through experiences and people I’ve known in one or the other of them. I think many people in the city feel the same thing. As you enter increasingly into a new linguistic and cultural sphere, your own identity changes: I’ve read as much in Spanish and French in my life as I have in English. If someone asked me about my own literary affinities, I’d mention the Argentine experimental poet Oliverio Girondo, as well as Allen Ginsberg, Claude Gauvreau, and Aimé Césaire. Gradually the multilingual person begins to inhabit a unique, eclectic cultural space. Even the news and world affairs are different, depending on the language in which you read or experience them. Of course, the languages often mingle, interact, and jostle one another, so that I know I use anglicisms and hispanisms in French, and gallicisms in English and Spanish; often this mélange or mestizaje ends up in unusual or original phrasing, which enriches the other language. Authors that write in an adopted language, such as Joseph Conrad or Samuel Beckett, bring a new tone and way of expression to their work, as do allophone writers in Canada.

You’re fluent in at least four languages. Is there spillage? Like many polyglots, do you find that some words just fit better in one language or another?

Yes, there’s a lot of spillage, and I sometimes use an expression in one language that is a calque from another. I find I think about my words more, weighing them, wondering where they come from, trying to make sure they’re not set phrases and lifeless clichés. I like to play with words, use them in odd ways, listen for dialect and usage, make them up, or simply use some of their sounds. Montreal gets under your skin: when I’m in a unilingual environment, I feel a bit frustrated at not being able to make multilingual references like you can here. There’s a Canadian writer named Gisèle Villeneuve, who grew up in Montreal and now lives in Calgary, who has written a novel in a mixture of French and English, blending the two languages in the same sentence. That style comes naturally to her, and in Canada there’s an audience that can appreciate it! Translation is always possible, at least to an extent: Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake, which is almost impenetrable in English, has been translated into many languages. The Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset has an essay called “Miseria y esplendor de la traducción” in which he says that although translation is inherently impossible, it must be attempted.

You frequently translate from sister languages, notably Portuguese and Spanish. Is there one or another that fits better?

Most of my translation has been from French and Spanish into English. Despite travelling extensively in Brazil and studying Portuguese at the Université de Montréal in the 1990s, I’ve only been able to integrate it into my life more fully during the last five years or so, as I’ve worked increasingly with Brazilian and Portuguese literature. I also self-translate much of my own work into Spanish and French, and have publications of my poetry in those languages now as well as in English. One advantage to self-translation is that, since the work belongs to the writer, he or she can take more liberties than they would if they were translating the work of someone else. Inevitably, self-translation leads to the creation of a new, independent text in the target language.

I’ve spent so much of my life working in Spanish, including twenty-five years teaching mainly Spanish translation, Latin American civilization, and the history of the Spanish language at Concordia University, that it’s second nature to me. The same goes for French, particularly since much of my family life here in Montreal has been in French, as have my studies. Although they’re Latin-based languages, French, Spanish, and Portuguese all present particular challenges in translation. French influence is such an important part of English vocabulary that one has to constantly be aware of the pitfalls of using false cognates or overly Latinate expressions. Words of Anglo-Saxon origin almost invariably have more power and resonance in English, particularly in poetry, though it’s also interesting to explore some lesser-used words of Latin origin too. Spanish and Portuguese come from more distant cultural and geographical spheres, enriched by Arabic, Amerindian, and African vocabulary, and there is an incredible range of national variations in Spanish and of regional diversity in Brazilian Portuguese, which is often challenging to convey. I tend to concentrate on the translation of writing of the Americas, and there are many historical and literary characteristics that are shared by the nations of the hemisphere. They are all cultures of fusion, and their languages also include numerous expressions from urban slang, rural dialects, older uses that have gone out of style in Europe, mixtures with immigrant languages, and other factors particular to the New World.

You’ve translated both prose and poetry over the course of your career. How would you describe the translation of poetry? Do you think only those who write poetry themselves can or should translate poetry?

In all three languages, of course, it is the more experimental and cutting-edge literature that is the most challenging to translate, whether it’s poetry or poeticized prose, and that is what I most enjoy. Translation of classical verse forms, such as sonnets, into similar verse and metrical forms is also difficult, but for somewhat different reasons. Some prose is stylistically so ornate, with sentences that turn back upon themselves and elaborate baroquely on their content, that it’s basically poetry composed in linear form. Poetry itself, by its concision, ambivalence, and play with connotation and multiple interpretations, is uniquely stimulating to translate. Sometimes the translator has to accept that the same richness in meaning or sound may be difficult to express in a given phrase, and search for other places in the poem to bring out similar effects. I don’t think that one necessarily has to be a poet to translate poetry, any more than one has to be a novelist to translate a novel. So long as the translator has a keen awareness of the possibilities of poetry and the linguistic complexity inherent in it, he or she should be able to produce a fine translation. There are a number of great poets, such as Ezra Pound, who enjoyed translating but would become frustrated and impatient with conveying the original text as faithfully as possible, and tended to write adaptations of the original poem rather than actual translations. On the other hand, up until the nineteenth century, many European poets would translate the Greek and Latin classics not simply for publication, but essentially to sharpen their own styles. Poets and prose writers can learn a great deal by inhabiting the words of authors they admire and giving voice to them in another language.

How did you get started as a literary translator?

My first literary translations were poems and short stories by Latin American friends of mine here in Montreal who wanted to make their work available to English-speaking audiences and, in some cases, were putting in for grants from the Canada Council. There was quite a lot of interest in their work among literary journals and small presses, and, since the Canada Council gives grants for the translation and publication of work from third languages into English and French, I was able both to follow my academic interest in Hispanic-Canadian writers and to translate their works. I also began translating Quebec poetry for several literary reviews. The first of these was ellipse: Textes littéraires canadiens en traduction/Canadian Writing in Translation, which was then affiliated with the Université de Sherbrooke, where I was doing my doctorate in Comparative Canadian Literature. I’ve worked with ellipse ever since. The second was Ruptures: la revue des Trois Amériques, founded by Edgard Gousse, a Haitian-Canadian writer who had studied in Buenos Aires, and Jean-Pierre Pelletier, a Quebec poet and translator. Ruptures published material from all over the Americas and beyond in the four European languages of the Western Hemisphere: Spanish, Portuguese, English, and French. It put out fourteen issues during the 1990s, some of them running over three hundred pages, which allowed me to translate an enormous range of writers. I ended up coediting the review with Edgard, and we published special issues on the literatures of various regions and nations, including Quebec, Mexico, the Caribbean, the Southern Cone, and Venezuela.

You have often translated émigrés, particularly Spanish-language writers living in Canada. How have those multiple levels of remove, that added distance, changed your perspective as the translator? As a reader?

I’ve always been particularly interested in the literature of the Americas, and in comparisons between Canadian and Latin American writing. As an immigrant myself, and with a number of Spanish and Portuguese-speaking friends who also immigrated to Canada, I felt a particular affinity with writers who continued their work in a new and often strange environment. I was also amazed at the originality, breadth, quality, and sheer energy of their work, which they continued undaunted after arriving in Canada, often publishing in small Spanish-language publishing houses that flourished here. Some were already well known in their country of origin and beyond; others began to write after arriving here. Exploring and translating their work led me to increasingly deeper explorations of their various national literatures and traditions, and enriched my own knowledge of Latin America. I was also intrigued by how each of them adapted to the specific culture and region of Canada where they settled; the difference between moving into English or French-speaking areas and literary traditions was particularly interesting and is something that I researched intensively in my book Latinocanadá: A Critical Study of Ten Latin American Writers of Canada.

Montreal is also a point of intersection for indigenous authors and writers from French and English-speaking countries from around the world, whether it be the Caribbean, the Maghreb, Lebanon, East Africa, or India. I’ve always had a particular interest in the literature of the French Caribbean, and was delighted to find such a rich and varied world of Haitian writers in Quebec. I translated a number of poems by Haitian-Quebecers for the collection Compañeros: An Anthology of Latin American Writing that I brought out with Gary Geddes in the early 1990s, and my interest in their writing has continued ever since. In many respects, the Italian and Haitian-Canadian writers in Montreal led the way for the Latin Americans who came after them.

In this issue of the Malahat, you have translated poems by the Brazilian Zulmira Ribeiro Tavares—a glimpse of a book published in August of this year—the first time her poetry has been published in English. I find it hard to believe she hasn’t been translated into English before—there is a wryness to her work that is really well conveyed in English—“Desejamos os pingüins de nosso assombro”/ “We want the penguins of our astonishment”… What drew you to her work?

I first translated poetry from Portuguese in the 1990s, and was lucky enough to translate an essay by Leonardo Boff, a Brazilian theorist of Liberation Theology, a few years later. Then, about a decade ago, I became increasingly active in research into Brazilian literature, as well as in the dissemination of Canadian literature in Brazil. The Brazilian Association of Canadian Studies (ABECAN) is the largest and most active organization of its kind in Latin America, and there is great interest in Canadian and especially Quebec poetry in Brazil. In 2011 I worked with two professors from Brazil, Sonia Torres and Eloína Prati dos Santos, in bringing out a special trilingual double issue of ellipse (Nos. 84–85) dedicated to contemporary Brazilian literature. Sonia and Eloína’s selection was excellent—a broad range of strong Brazilian writers, with a wide variety of styles and themes—and I particularly liked the poems by Zulmira that were included. I translated one of them, “Jibóia” (“Boa”), along with a short story by Márcio Souza. I was struck by the precise, evocative language of Zulmira’s poetry, as well as by the subtle bite of her playful irony, which often comments on the artifice of writing itself as it attempts to grasp events or people that inevitably dissolve—like itself—into the fluidity of time. Eloína contacted her for me, and Zulmira sent me a copy of Vesuvio, her latest book of poems, along with a book of her prose poems and mini-fictions, and a novel.

The imaginative, surrealist quality of much of her work, with unexpected and often ambivalent imagery, and a translucent style in both her prose poems and poetry delighted me, as it did Noelle Allen, the publisher of Wolsak & Wynn, with whom I had worked before. Zulmira has been writing since the 1960s: her work has received a number of awards, and her distinctive style is well known in Brazil. Several of her novels had previously been translated into Italian and German, and she herself has translated work by the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard into Portuguese, but none of her work had been brought out in English. This surprised me, but also underlined the extent to which Brazilian literature receives less attention in the English-speaking world than does that of Spanish-speaking Latin America. Perhaps there was a synergy to this, because the British translator David Hahn was also making arrangements to translate two of Zulmira’s novels, Family Heirlooms and The Name of the Bishop, at the same time.

You’re sharing the helm of the Banff translation program; you spent many years teaching at Concordia. While the two situations are different pedagogically, I wonder how teaching has informed or changed your own practice as a translator, and as a writer?

Teaching has immeasurably deepened my appreciation of translation and the linguistic and literary complexities it involves. The courses in Spanish translation that my colleagues and I established are popular at Concordia, and the students invariably brought new perspectives and insights to our discussions. All translations are asymptotic: they strive to arrive at the original but can never fully attain it. There are no perfect translations, only approximations, which is why great works are often retranslated every few decades or so. I learned a great deal, especially in advanced classes in which we worked alternatively from English to Spanish and Spanish to English, sometimes with a bit of French thrown in for balance. There were always a number of native Spanish-speakers in the class, as well as students from a number of other languages, including Portuguese and Arabic, and the courses included both direct translation of literary selections and material on the theory and history of translation, generally from a Spanish and Latin American perspective.

I’ve also learned an enormous amount from the discussions we have among the participating translators in the residency program in literary translation at Banff, which deals more with the actual dynamics of translation and of working in the field and serves as a counterpoint to more academic studies. Both experiences have made me aware of the tremendous variety of ways to go about translation and to take on the challenges in a given text, as well as of the myriad approaches to the central conundrum of the art: what balance to strike between the transparency of the translation and the need to bring new elements from the original text and source language into the cultural realm of the target language.

Does translating affect your writerly voice, and vice versa?

Of course it’s crucial to feel a strong affinity and even identification with the work that you translate: otherwise, translation becomes a task rather than a joy. I try to choose the works I translate carefully. Many—or even most—of the works I translate are in styles quite different from my own. Occasionally, though, I translate a work that resonates deeply with my own way of writing, and its style opens up new means of expression to me. I especially find this with more experimental forms of poetry, though also of prose. The staccato imagery and highly poetic prose of Alfonso Quijada Urías showed me just how much one could let loose, while the complex, intricate sentences of Pablo Urbanyi, which often made wry comments on the subject or description itself, made me aware of the ludic qualities of longer trains of thought. Girondo’s sound poetry, Nela Rio’s sensitivity to connotations, Hélène Dorion’s search for the implied, Joël Des Rosier’s neobaroque lushness, and paolo da costa’s affectionate deconstruction of national identity… The list could go on.

To what extent do you choose the work you are going to translate? How often are you approached by publishers, writers, agents, etc., to undertake a translation, perhaps of a writer of whom you’re not even aware? How do you decide whether an author or book has the sort of affinity that will make, for you, the intimate act of translation possible?

If I find a work especially interesting, I usually ask the writer about translating it. Sometimes, though, it’s the writer or publisher who approaches me. It’s quite rare for someone to ask me to translate a work by an author who’s totally unknown to me, although several years ago I was commissioned by Wolsak & Wynn to find and translate a young, promising Latin American woman poet who hadn’t previously been translated into English. I’d previously put together a special issue on current Argentine poetry for ellipse and had amassed numerous anthologies and was also familiar with a number of large websites, some of them with over a hundred authors, which are popular places to publish in Latin America. The author I finally found, the Argentine poet Griselda García, was fascinating—a unique voice from a new generation. I know almost immediately if I’m interested in translating a book: the affinity is something that I can feel almost viscerally. Sometimes it applies to the author’s production as a whole, but most often it’s for an individual work.

Forums for the presentation of literary translation tend to be few and far between. In Montreal, there are a couple—I’m thinking of the series you’ve involved with, Lapalabrava, or the multilingual cohabitation of the Blue Metropolis festival. The Union des écrivaines et des écrivains québécois (UNEQ—the Quebec writers’ union) and the provincial arts council, the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec (CALQ), sometimes also facilitate exchanges, to various degrees. Has the landscape for the presentation of literary translation changed? There are fewer dedicated translation publishers now… Is there a need for more exposure, either for translators, for authors, for the reading public?

There is a new and very strong interest in literary translation now, as well as in multilingual poetry readings, in authors such as Nancy Huston who write in different languages, and in self-translation, and we’re seeing a range of linguistic experimentation, including hybrid books, with sections in several languages, but without translation. Canada has always been a leader in translation between English and French, but now publishers are beginning to translate more work from abroad, often circumventing the lack of funding by co-publishing works with foreign presses. Literary reviews are much more interested in publishing translations than they once were, and there is a growing acceptance of literary translation as an art in itself (as its inclusion in the literary arts program of the Banff Centre notably shows). The dichotomy between publishing houses that specialized in translation and those that published no translation at all seems to be giving place to a new synthesis, in which a number of publishers include translated works in their catalogues. The reading public is certainly ready for it, as interest in world literature—like interest in world music and art—expands. A novel by a well-known author may now be published in a dozen or more languages, and a play might be produced in different countries all over the world. Literary translations from English to other languages are already legion, but translation into English is also an increasingly integral part of Anglophone literature, bringing new voices and cultures to the fore. The important thing for translators is to make sure their work is recognized, respected, and discussed.

Do you have favourite translators, translators whose work you seek out specifically, regardless of the author they’ve translated? What do you particularly admire in their work?

Most translations that I read are of works from languages that I don’t know, so the only thing I can really tell is how fresh and alive the translation is, especially if it’s of a high-quality writer. When I do listen to or read translations of works between languages I know, I’m obviously more able to judge what the translators have done, and sometimes find it absolutely extraordinary. What I particularly admire, both in experimental work and also in complex, traditional styles, is a translation that manages to remain as faithful as possible to the original, while flowing smoothly and naturally in the target language. Of all the translations of Don Quixote, I still prefer that of Thomas Shelton, the very first translator, who published it in English only six years after the book appeared in Spain. For Shelton, the Quijote wasn’t a sacred, canonized text: it was simply an amazing book that had just been published in Spain and that he wanted to share and, despite its various translation errors, his Elizabethan language and phrasing has the vitality and energy of the original, which makes all the difference.

Katia Grubisic

* * * * * * * *