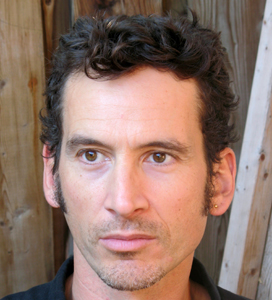

The Nightmind: Adèle Barclay in Conversation with Steven Heighton

Poet Adèle Barclay speaks with Steven Heighton, judge for the 2016 Far Horizons Award for Poetry (deadline May 1, 2016). The two discuss the poetry that compels him, his advice for emerging writers, and the best and worst film of all time.

Whether you’re reading a periodical, a collection, or contest submissions, what kinds of poems catch your attention and stick with you?

My answer to that question changes all the time, depending on what's happening in my life or in the world. Right now the poems that most compel me are the ones that choke me up—poems that could rip the heart out of a wheelbarrow. I'm also gravitating toward work that emerges from the nightmind, as I call it—poems born of dreams and hallucinations. Weird, oneiric stuff. By the same token, I'm tired of poems that seem primarily to be auditioning for a collegial constituency, demonstrating the poet's fluent familiarity with the films, songs, shows, apps, etc. that he or she knows colleagues to be co-immersed in. Intertextuality of that kind can be brilliant and effective, for sure, but only in the context of work emerging from some deeper psychic impulse. More and more what Philip Larkin said about poems makes sense to me: "I didn't go looking for them, either." I guess that's it: the poems that compel me are, or at least seem to be, received, not devised.

You’re a prolific writer of poetry, novels, and short stories. How does your prose writing inform your poetry and vice versa? How do the forms overlap and what does poetry allow you to distinctly explore?

I'd say that prose doesn't much get into my poems. At least I hope not. My poems are more lyrical than narrative. So there's little overlap in that direction. Alas, in the other direction . . . Writing a novel, or even a 25-page story, while paying attention to the language like a poet (ie, on the level of the syllable instead of the sentence) is slow death, but what am I to do? A writer's ear makes certain demands; you can't walk away from a sentence until it feels right.

As for what poetry allows me to explore, I'd say it frees me from the demands and designs of narrative. And there are real demands. If you want a reader to stick around for 300 pp, you'd better tell a good story, one way or another. But in a ten line poem, you have absolute freedom. (If, at a dinner party, you describe a meandering, storyless dream you had and you go on for a while, don't expect a return invitation. But an eight line evocation of a dream, if it's interestingly psychotic or hallucinatory, may well fascinate your audience—who, after all, are poets themselves.)

Tell me about the novel you’re working on finishing up right now.

It's called, at least for now, The Nightingale Won't Let You Sleep and it's set in present day Cyprus. It should be appearing next spring.

What advice do you have for emerging writers submitting to contests and beginning their careers?

Well, here's some advice I'd give to my younger self if I could. (God, if only.) These memos, as I call them, were first written for a magazine [TNQ] that asked authors what they wish they could have told their younger selves about writing. Now they're part of a small collection of "memos" and essays called Workbook:

1 Interest is never enough. If it doesn’t haunt you, you’ll never write it well. What haunts and obsesses you into writing may, with luck and labour, interest your readers. What merely interests you is sure to bore them.

2 Let failure be your workshop. See it for what it is: the world walking you through a tough but necessary semester, free of tuition.

3 Embrace oblivion. The sooner you quit fretting about your current status and the long shot of posterity, the sooner you’ll write something that matters—while actually enjoying the effort, at least some of the time.

4 Allow yourself to enjoy it. Squash the temptation to accentuate, poeticize, or wallow in the difficulties of the writing life, which are probably not much worse than the particular difficulties of other professions and trades. Take a tradesman’s practical approach to your development: quietly apprentice yourself to language and the craft, then start filling up your toolbox, item by item, year after year.

5 Ignore Lord Byron, who wrote that “We of the craft are all crazy.” He was largely right, of course. Ignore him anyway. To romanticize the Writer as pursued by Furies, enthused by Muses, beset by demons—this is nothing but professional self-importance and self-pity. Writers have no monopoly on poverty, humiliation, self-doubt, or aggressive inner demons. Close your door and get on with it.

7 In writing, as in life, “personality” is not character. Never try to be cute, to be winning, to audition for the reader.

8 Never try to be cool. A writer afraid of seeming square will never write anything truly cool. The purest definition of cool, after all, is not caring what people think.

12 Stop straining to be “original” and, with luck and applied time, it just might happen.

13 You can only write authentically within the bounds of your own sensibility, but you can read and appreciate far beyond them. To develop a broad and generous vision, you’ve got to.

14 You don’t “graduate” from poetry to short stories, or get promoted from stories to the novel. The only graduation is to better writing.

15 Careerist writers don’t have friends, only allies. This is reason enough not to be careerist.

16 Careerist writers don’t confront and relish challenges, they crash into obstacles, which they naturally resent and fear. This is reason enough not to be careerist.

17 There can be just one final arbiter of your work. Refuse to appoint anyone else as your judge and appraiser, executioner, potential approver—the one reader, fellow-writer, critic, editor, or publisher whose acceptance of your work will stand as an ultimate verification, a proof of arrival, relieving you of that impostor-feeling every artist knows (a feeling that simply shows your aesthetic conscience is still active.) Resign yourself to the road, there’s no arrival. There’s no map either, come to think of it, but the sun is rising and the radio is on.

What was the last good book you read and why did you enjoy it?

I'm always reading, or dipping into, a number of books at once, so instead of trying to answer your question I'll tell you about the best film I've seen lately. No, the worst film. OK—the best and the worst at the same time. It's the cult classic Zardoz, made in 1974 by John Boorman (his previous film was Deliverance). Apparently Boorman dropped a lot of acid while making the film. I don't doubt it. Among other remarkable elements, Zardoz boasts a hirsute Sean Connery running around in high boots and a scarlet diaper. Oh, and a giant, flying stone head that utters the words, "The gun is good . . . the penis is evil!" Zardoz is a fantastic sample of 70s experimental psychedelia. You can watch it while ingesting nothing stronger than coffee and yet, by the end, you'll feel thoroughly stoned. It's brilliantly bad. I think I've just talked myself into watching it again.

Adèle Barclay

* * * * * * * *