Poems Unafraid: Sarah Brennan-Newell in Conversation with Yusuf Saadi

Malahat Review volunteer Sarah Brennan-Newell talks with 2020 Far Horizons Award for Poetry judge—and 2016's Far Horizons Award for Poetry winner— Yusuf Saadi about being on the other side of the contest process, how there’s no formula for a great poem, and how poetry can renew our belief in possibility.

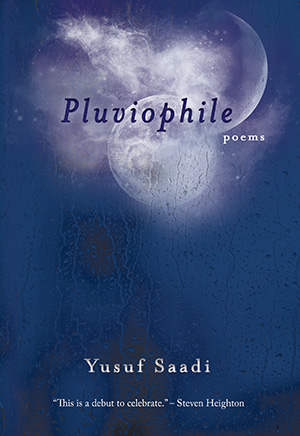

Yusuf Saadi’s first collection is Pluviophile (Nightwood 2020). His writing has appeared in journals including The Malahat Review, Vallum, Brick, Best Canadian Poetry 2019, Best Canadian Poetry 2018, Grain, CV2, and Canadian Notes & Queries. He also won the 2016 Vallum Chapbook Award and The Malahat Review’s 2016 Far Horizons Award for Poetry. He holds an MA in English from the University of Victoria.

Congratulations on being asked to judge The Malahat Review's Far Horizons Award for Poetry this year! As a winner of this award in 2016, how does it feel to be on the other side of the process?

Thank you! Receiving that award was very meaningful for me. I’d never won a poetry award before, so I had that “I can’t believe this happened to me” feeling. I’d also recently finished my MA at the University of Victoria where The Malahat Review is based; it was gratifying to be recognized by people I looked up to. I learned one of the poets I had researched for my MA, Derek Mahon, had published in The Malahat Review decades ago, which was unexpected since he spent most of his life in Ireland. In short, I had many surprising but pleasant emotional connections to The Malahat Review. Being able to judge the contest is a special honour because of this. I hope the award brings assurance and courage to the winner as it did for me, and gives them the confidence to keep sending out their work.

Building on that, as a judge, what are you looking for in a winning entry? What separates a good poem from a great one?

I certainly won’t be ticking a checklist as I’m reading through poems, but I’ll be transparent about what I tend to admire. Lyrical poems that dream of being song and unabashedly flaunt formal elements—metres, rhymes, traditional forms, etc. Wince-inducing imagery. Poems that reach for the sacred—I don’t primarily mean in a religious sense, but that’s possible too. A poem whose surface language is enjoyable on an initial read and reveals depth on rereading. Poems unafraid of desire, intimacy, sadness.

A great poem makes you feel it a miracle that a human being brought it into existence. There’s no formula for it; it shows you something you’ve never seen before. In contrast, I tend to dislike poems which are derivative of pre-meditated ideas and/or are derivative of academic ideas.

In a previous interview with The Malahat Review, you spoke about your writing process—I'm curious about whether you've noticed any changes in your process since then. Do you still feel anxiety in writing first drafts, and if so, do you cope with that any differently or is it still on a poem-by-poem basis?

I do still feel anxiety when writing. Each time I enter a new poem, it feels as if I’m entering somewhere unmoored, without clear signposts or markers, and I hope something shows me the way. (If it didn’t feel like that, wouldn’t one be writing the same poem over and over again?) However, I don’t get too down if a first draft is bad, as it usually is. I’m a chiseler; when I sense something is there, even if it’s in the distance, I just keep picking away at it bit by bit and sometimes, as if a gift were buried there for me, I eventually find something that intuitively feels correct.

I was struck when reading “Made in Bangladesh” and “Child Sacrifice” on your website by a sense that you were using your words very deliberately as a call to action, evoking the desire for change. What do you think poetry can give us that nothing else can? Are there any poems in particular that you feel expanded or changed your perspective?

I didn’t intentionally write those poems as a call to action, so it’s interesting you read them that way (and I don’t mean to suggest your reading is not valid!). Poetry can use language in ways that aren’t bound by our dominant ways of knowing/seeing, and thus can gesture toward things we sense but are outside of what we usually name, things beyond names though they may be intimately close. If you find the precisely correct sequence of words, maybe you can glimpse something about that nameless world and bring it into language. This can remind us how much unknown we are always surrounded by, how tenuous our arrogance about reality can be; it can renew our belief in possibility, in enchantment.

I’ve admired since I first read it a poem by a previous winner of the Far Horizons Award—“Song” by Kayla Czaga. It’s quiet but swells into a composition, creates intimacy through its melodic language that’s beyond the ordinary uses of its words. I am also very much in awe of last year’s collection heft by Doyali Islam. So many of its poems move right to the edge of language, to give a sense of what’s beyond it. I think she is a real poet. She pays attention to the world very deeply.

Have you been reading anything good lately? Is there anything on your must-read list for 2020?

I haven’t been reading books/films in any intentionally systematic way as of late, so this answer will be a scatter of things that recently left an impression on me. Last week, I saw this short “moving image” called Mute Grain by Thao Nguyen Phan about the 1945 Vietnamese famine; it was haunting—I watched it five times. I’ve also been watching and thinking about older Bengali films, particularly Ritwik Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960) and Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar. I loved Parasite as well—I’m ready to watch it again. The most recent book I read was Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous—when it hits its stride the language is so beautiful and intimate it made me tear up. Over the summer, I would like to read work by poet Jibonanda Das and novelist Réjean Ducharme.

Can you share anything about what your next writing project(s) might look like?

My first poetry collection is coming out from Nightwood this spring and I don’t think I’ll have closure on that until it’s completely done. I had a novella I was previously working on about partition and independence in South Asia; I’d like to revive that, though I was struggling with it and have lost some faith I’ll ever quite get it right. I also have also a few ideas for new poems; I want to think more about what “home” means. I’m a slow writer, though.

Sarah Brennan-Newell

* * * * * * * *