Reviews

Fiction Reviews by Brenda Proctor

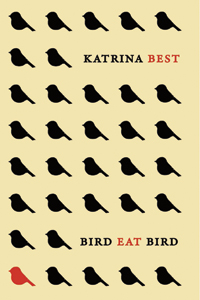

Katrina Best, Bird Eat Bird (London: Insomniac, 2010). Paperbound, 166 pp., $19.95.

Paul Headrick, The Doctrine of Affections (Calgary: Freehand, 2010). Paperbound, 200 pp., $23.95.

The first line in Katrina Best’s Bird Eat Bird thematically frames her debut short  story collection: “The pelican took its time swallowing the pigeon, keeping its mottled prey in the sack of its bill for almost half an hour.” With verve and quirky humour, Best creates colourful yet somewhat disconcerting images for readers to examine, such as closeups of the pigeon-eating pelican, an adrift boogie-boarding mom, and vibrating tripe splayed across a grocery aisle. Best also adjusts her word lens and zooms outwards. She provides readers with the internal and spoken commentaries of onlookers, narrators, and central characters, provoking thoughtful reflections in vibrant, clear, and upbeat prose. Her easy-to-read stories bravely tackle the darker shades of relationships and tendencies towards obsession and secrecy amongst parents, family members, co-workers, a dating couple, and teens while drawing attention to the unreliability of perception. Best’s stories reflect both her British upbringing and her time in Canada, as humour and scenarios from both cultures enter her stories. This first-time author’s skills at creating strong images and illuminating them from humorous angles shine perhaps in part because of her time spent as a screenwriter, script analyst, and story-editor, as well as her experience working on a low-budget Canadian TV series.

story collection: “The pelican took its time swallowing the pigeon, keeping its mottled prey in the sack of its bill for almost half an hour.” With verve and quirky humour, Best creates colourful yet somewhat disconcerting images for readers to examine, such as closeups of the pigeon-eating pelican, an adrift boogie-boarding mom, and vibrating tripe splayed across a grocery aisle. Best also adjusts her word lens and zooms outwards. She provides readers with the internal and spoken commentaries of onlookers, narrators, and central characters, provoking thoughtful reflections in vibrant, clear, and upbeat prose. Her easy-to-read stories bravely tackle the darker shades of relationships and tendencies towards obsession and secrecy amongst parents, family members, co-workers, a dating couple, and teens while drawing attention to the unreliability of perception. Best’s stories reflect both her British upbringing and her time in Canada, as humour and scenarios from both cultures enter her stories. This first-time author’s skills at creating strong images and illuminating them from humorous angles shine perhaps in part because of her time spent as a screenwriter, script analyst, and story-editor, as well as her experience working on a low-budget Canadian TV series.

The vitality that makes Best’s stories so appealing has its occasional drawbacks. At times, Best’s stories exaggerate too much, and some sections lost my attention, especially in “Tall Food,” where the narrator’s point of view exposes a personality who not only lacks self esteem, but also intelligence. This character’s reflections on her dating life were almost painfully funny to read, but arguably a bit too pathetic to be convincing. Still, throughout the collection, Best bravely switches viewpoints, writing from the perspectives of vastly differing characters, including one who’s mentally ill (“Red”). In “Tea Leaves,” a rather shallow retail clerk narrates how she allows her friend to be arrested in her place—with a humorous twist. Although all Best’s stories are worth reading, “Lunch Hour,” “Tea Leaves,” and “Tripe and Onions” are particularly strong and had me laughing or shaking my head in appreciation, and reflecting on ethics, human behaviour, and the intricacies of perception.

Paul Headrick’s short story collection, The Doctrine of Affections, is as provocative  and engaging as Bird Eat Bird. Headrick’s novel, That Tune

Clutches My Heart, was published in 2008 and shortlisted for a B.C. Book Award, and Doctrine, his second book of fiction, is equally promising. Doctrine’s style is eloquent and ironic, exploring musical ideas in clear prose, often creating acoustic images. Musical and tin-eared readers alike will appreciate the ways Headrick orchestrates musical themes throughout his stories, including the baroque idea that a musical piece “should arouse a single emotion in the sensitive listener.” And indeed, Headrick’s characters encounter melodies as emotionally transformative: A guitar virtuoso dying of throat cancer is “able to forgive himself, listening to the notes of one of his nameless studies.” In some cases, music informs the rhythm, atmosphere, or plot of the story. In “Rosie,” a young girl feels the joyful “music of [her] skates as they click over the cracks in the sidewalk” and feels its “vibrations in her knees,” inspiring song to spill out of her. And in “After Chuck Blakeney Died,” the way two friends listen to the “odd, fractured solos” in Blakeney’s jazz and what the music “leaves out” foreshadows their interwoven responses to issues of infertility and heroin addiction.

and engaging as Bird Eat Bird. Headrick’s novel, That Tune

Clutches My Heart, was published in 2008 and shortlisted for a B.C. Book Award, and Doctrine, his second book of fiction, is equally promising. Doctrine’s style is eloquent and ironic, exploring musical ideas in clear prose, often creating acoustic images. Musical and tin-eared readers alike will appreciate the ways Headrick orchestrates musical themes throughout his stories, including the baroque idea that a musical piece “should arouse a single emotion in the sensitive listener.” And indeed, Headrick’s characters encounter melodies as emotionally transformative: A guitar virtuoso dying of throat cancer is “able to forgive himself, listening to the notes of one of his nameless studies.” In some cases, music informs the rhythm, atmosphere, or plot of the story. In “Rosie,” a young girl feels the joyful “music of [her] skates as they click over the cracks in the sidewalk” and feels its “vibrations in her knees,” inspiring song to spill out of her. And in “After Chuck Blakeney Died,” the way two friends listen to the “odd, fractured solos” in Blakeney’s jazz and what the music “leaves out” foreshadows their interwoven responses to issues of infertility and heroin addiction.

Headrick’s focus on music at times leaves some characters and scenes only vaguely described. In “Traveller’s Song,” most characters and the landscape remain nameless and nondescript. This effectively highlights a powerful musical moment when a nomad sings “waves of deep notes rising and falling” to a young man masquerading in darkness as a stolen mule. However, the story’s sparse, generic descriptions of the young man’s “sisters,” “village,” and “hut” distract from the story’s sly plot. In contrast, when writing about academia, Headrick tends to be more explicit and compelling, perhaps because as an instructor at Langara College, academia represents familiar territory. In “The Franklin Chair,” Headrick reveals the underlying tensions of academia by sketching a sessional instructor’s interview for the position of the Franklin Chair—a job she has no chance of getting. Doctrine’s highlights nestle not just in the musicality of each story, but also in each character’s intense longing for meaning or connection— the sessional instructor obsesses about one of her students (“The Franklin Chair”), six-year-old Hannah jabs and punctures four-year old Nathan with a pick-up stick (“The Young Gods”), and an engineering student strives to feel something other than an “imitation” of who he thinks he ought to be (“After Chuck Blakeney Died”). At his best, Headrick interweaves poignant storytelling and narrative twists with a powerful ability to stimulate reflection about the power of music and its relationship to emotion.

—Brenda Proctor