Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Mark Callanan

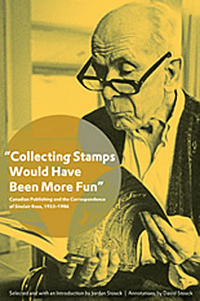

Sinclair Ross (selected and with an introduction by Jordan Stouck; annotations by David Stouck), “Collecting Stamps Would Have Been More Fun”: Canadian Publishing and the Correspondence of Sinclair Ross, 1933-1986 (Edmonton: University of Alberta, 2010). Paperback, 304pp., $34.95.

“I always run to meet rejection,” Sinclair Ross wrote in a 1955 letter to John Gray, former editor in-chief at Macmillan Canada, which published Ross’s ill-fated 1958 novel, The Well; “and not only where manuscripts are concerned. Perhaps it has become a kind of insurance against disappointment.” Given the ego’s frequent blindness to its own deficiencies, it was a particularly astute observation on Ross’s part. Sadly, this self-knowledge was often paired with an inflated sense of his own failings as a writer.

“Collecting Stamps Would Have Been More Fun” is a compilation of Ross-related correspondence (his own letters, those of his correspondents, and a small number written about him by other parties), that reveals an author plagued by self-doubt, enduring frequent rejection by North American publishers, and, eventually, after suffering the ravages of Parkinson’s disease, dying in Vancouver at the age of eighty-eight. “I would be grateful if you would ignore me,” he wrote, toward the end of his life, in response to an interview request for a forthcoming anthology. And while this disinclination to be interviewed was typical of Ross (the typescript of the only formal interview he participated in is printed as an appendix to Collecting Stamps), it’s difficult not to read a certain morbid resignation in his plea to be left alone.

Whether Ross’s frequent epistolary self-deprecation was further “insurance against disappointment,” or false modesty intended to illicit compliments to feed an etiolated ego is difficult to discern. Truth be told, he came in for no small amount of praise. Margaret Atwood’s canonization of As for Me and My House in her seminal study of Canadian literature, Survival, spurred much belated interest in Ross’s work. Over the course of his career, he was lauded by the likes of Margaret Laurence, Guy Vanderhaeghe, and others, many of whom cited him as a powerful influence on their own development. None of this seemed to dispel his pervasive feelings of failure. It is frustrating, as a latterday reader, to watch him eternally apologizing for his writing. Writing to Pamela Fry, who edited his 1970 novel Whir of Gold for McClelland & Stewart, he described feeling “guilty and ashamed, in fact, to be taking up [her] time with it. Spotty, slack, dull, pointless—a big So What? on every page.” In his initial query letter to Fry, the greatest virtue he could muster, in speaking of the manuscript, was that it was “short” and, thus, “a reader will run through it quickly.”

Perhaps as a way to protect his wounded pride, the later Ross was a revisionist of his early career aspirations. Writing in 1977 to the editor of Canadian Fiction Magazine, he insisted that he “never thought of [himself] as an author working in a bank” (an occupation he held for forty-three years), but as “a bank clerk trying to do a little writing on the side.” Yet his early correspondence, including a 1941 application to the Guggenheim Foundation, which cited his intention to quit his bank job, would suggest he took his work seriously enough to consider writing full-time. The Guggenheim application was turned down, and Ross resigned himself to his day job—in part out of a sense of financial responsibility for his aging mother, who was in his care. The publication of As for Me and My House in 1941 was not the commercial success Ross might have hoped it would be. It was not until McClelland & Stewart re-released the novel, as part of its New Canadian Library series, that it gained a significant readership. “I get horribly depressed at times—being ‘doomed’ to write what no one wants to read,” he wrote in 1943 to Earle Birney. He may have been correct in this estimation of his limited appeal: apart from the writing collected in The Lamp at Noon and Other Stories, his later publications made little impact.

It’s impossible to predict what future generations will make of Ross’s body of work. “It may be,” as Sheila Kieran (a writer who conducted an informal interview with Ross while he was living in Spain in the 1970s) so pointedly put it to a friend who’d taken out a film option on As for Me and My House, “that this man—everyone’s bank clerk uncle—had one good story in him, and that one a masterpiece. Who knows?” If his letters are any indication, Ross completely failed to grasp the impact his writing had had on western Canadian literature; it is unutterably sad to think he died believing himself a failure.

—Mark Callanan