Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Amy Reiswig

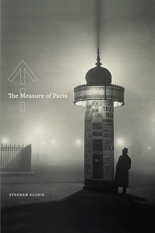

Stephen Scobie, The Measure of Paris (Edmonton: University of Alberta, 2010). Paperbound, 356 pp., $19.95.

“We’ll always have Paris.” Bogart’s immortal farewell in Casablanca could also serve as a fitting conclusion to Stephen Scobie’s recent book The Measure of Paris. Here, he explores the iconic city as not only a place but an inexhaustible, mutable idea that shapes and is in turn shaped by those drawn to walk its streets. Paris, Scobie claims, is a city that “never ends.”

“The impulse to write about Paris,” therefore, “is irresistible,” Scobie admits. “People never tire of attempting to ‘measure’ Paris or of offering their own personal accounting of its history, its allure, the endless fascination of its sheer existence.” Initially intending the book as a study of Paris in the writing of several Canadian (and a few crucial American) authors, it’s clear that poet, professor, and literary critic Scobie’s own fascination with the “infinite city” took over, resulting in a 275-page book (plus another thirty pages of endnotes) that both analyzes and adds to the cycle of reinvention—people who read about Paris, visit, then “transform this experience into art…move from walking to writing, from being a flâneur to being an écrivain.” Scobie’s career as an écrivain is already well-established. Having published several full-length critical studies, numerous essays, short stories, and over a dozen books of poetry (including one specifically about Paris, McAlmon’s Chinese Opera, which won a Governor General’s Award), Scobie is clearly a man of keen and dynamic mind. But this book also shows us a man in love—in love with his subject, with literature, and with the personal Parisian experiences he shared with his wife, whose memory and influence are touchingly honoured in the book’s later chapters. Scobie’s personal and intellectual love of Paris drives him to extraordinary depths of research. “Paris is written as poetry, as history, as politics, as sociology, as memoir, as urban geography, as autobiography,” he tells us, and he discusses them all, focusing specifically on the nostalgic trope of “Paris perdu,” the implications of Paris’ transformation under Haussmann in the 1850s, the genre of 1920’s Paris autobiography, the history and ideal of the flâneur, the literary practice of precise street naming, and the multivalent significance of various Parisian sites. Specific chapters also look at the above in works by Canadian authors Mavis Gallant, John Glassco, Sheila Watson, Gail Scott, Gerry Shikatani, and Lola Lemire Tostevin as well as in the Parisian writing of Gertrude Stein and Djuna Barnes.

However, a peril of writing about Paris—and about so many writers writing about it—is how to fit something untidily “infinite” into the necessary organization of a readable publication. Scobie is aware of this, and his introduction straightforwardly explains that “the stance and tone of this book shift from chapter to chapter—sometimes as literary criticism, sometimes as cultural history, sometimes as personal memoir. What holds the book together is Paris itself.” This unconventional stylistic blend is part of what makes the book so engaging. But this shifting style also produces some jarring turns on Scobie’s Parisian tour. For instance, after plunging into the fascinating mélange of Paris’ history, geography, politics, art, architecture, etc., in Part One, the abrupt shift to literary criticism in Part Two came as a bit of a disappointment. While it works as a stand-alone study—it was included in American Modernism Across the Arts (Peter Lang, 1999)—Scobie’s discussion of autobiographical technique in Stein, Glassco, McAlmon, and Scott (for example: “The narrator must always be ‘the other,’ occupying that place of alterity from which the authorial ‘I’ can look at the protagonist, and at herself, as if from a distance”) feels somewhat disconnected from the previous section. It is only at the end of the chapter that he returns more specifically to Paris, briefly connecting narrative strategy to experience of the city itself.

A similar jump occurs between Parts Four and Five. Readers get comfortably settled on Rue Rousselet through Scobie’s descriptions of living there at various times—people he knew, places he frequented—but then are abruptly, without transition, shunted into detailed analysis of Tostevin’s Frog Moon and Shikatani’s Aqueduct. These sections are compelling for those who enjoy reading literary criticism or have particular interest in these writers, but this reader felt impatient at the interruption. Only in Part Six do we again return to Scobie’s own narrative, marked by love, loss, and longing, where he includes poems, journal entries, and recollections about his late wife. “Standing by the Seine that evening with Maureen, I knew that I was at home in the city of my dreams.”

One way to read these slightly frustrating rough cuts is in the context of the Parisian flâneur who, Scobie emphasizes, delights in “missing the direct way” or taking the more “devious routes.” Perhaps Scobie, like Julien Green, envisioned “writing a book about Paris that would be like one of those long, aimless strolls on which you find none of the things you are looking for but many that you were not looking for.” And, one might add, many that you will never forget. What emerges clearly from Scobie’s book is that Paris is indeed a city of dreams—a locus of memory, inspiration, and creativity that is continually dreamed into fresh myth and meaning by new visitors who are themselves subtly changed forever. As Scobie says, in an echo of Bogart, “There are many farewells to Paris, and none of them is ever final.”

—Amy Reiswig