Reviews

Poetry Reviews by Barbara Colebrook Peace

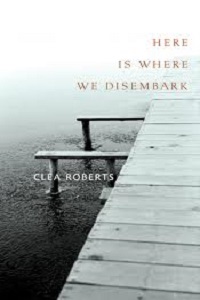

Clea Roberts, Here is where we disembark (Calgary: Freehand, 2010). Paperbound, 104 pp., $16.95.

Al Rempel, understories (Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin, 2010). Paperbound, 96pp., $16.95.

“Winter has carved / small caves / in our hearts” says Clea Roberts in her first  collection of poems, Here is where we disembark. If Winter were to write a book of poems, it might look like this: spare, minimalist, each phrase stark and self-complete on its own line, the short poems compacted like snow under its own weight. This is language dressed for survival—“The boots were rated for - 50 C / —you wore an extra pair of socks”—in poems that form both a meditative response to the landscape of northern British Columbia and the Yukon, and an exploration of the heart’s interior “caves” carved out by winter. The ethos of Roberts’ writing is ecological, taking only what is needful, retrieving more from less. Survival is a major theme, but there is a transcending joy and beauty in these poems. Throughout the work, the poet holds the tension between the small edge of human settlements, where “light becomes finite and coveted” in winter, and the vastness of the terrain: “the bright arteries of poplars / holding all the world’s / light and space in their branches.” Snow and survival are linked within the poet’s heart as she comes across someone on the trail in the woods:

collection of poems, Here is where we disembark. If Winter were to write a book of poems, it might look like this: spare, minimalist, each phrase stark and self-complete on its own line, the short poems compacted like snow under its own weight. This is language dressed for survival—“The boots were rated for - 50 C / —you wore an extra pair of socks”—in poems that form both a meditative response to the landscape of northern British Columbia and the Yukon, and an exploration of the heart’s interior “caves” carved out by winter. The ethos of Roberts’ writing is ecological, taking only what is needful, retrieving more from less. Survival is a major theme, but there is a transcending joy and beauty in these poems. Throughout the work, the poet holds the tension between the small edge of human settlements, where “light becomes finite and coveted” in winter, and the vastness of the terrain: “the bright arteries of poplars / holding all the world’s / light and space in their branches.” Snow and survival are linked within the poet’s heart as she comes across someone on the trail in the woods:

I feel like the weight of snow

as it slides from a roof

and slumps to the ground

but really it is the moment

of fall I inhabit

which is taut, endless,

until I shake her shoulder,

see the eyelash flutter.

(“Weight”)

Besides the luminosity of the writing, what I like best about this book is how inclusively and responsively Roberts writes, so that the book becomes not only the story of human beings but of other creatures, of natural phenomena, and of the landscape itself. It is also the story of snow. This is true from the first stanza of the book’s opening poem, “Transmutations”: “While we slept / the snow fell quietly / filling in the yard’s / grey and brown truths / with explanations / of eider and light.” It is especially true, however, in Part Two, where Roberts offers a series of poems on the Klondike gold rush, creating not a history but what has been called “mythistory.” (Interestingly, William H. McNeill, in his book Mythistory and Other Essays, refers to “mythistories that fit experience better and allow human survival more often.”)

In this section, structured as fourteen pairs of poems, the poet offers voices of community, landscape, and geographical phenomena in response to each other, call and answer. We encounter the women from this historical period, voices not much heard before, and it’s exciting to hear what they have to say. Alive here, and credible, pioneer wife speaks to the river, prostitute speaks to a sergeant, woman speaks to a king salmon; they tell unique stories of their longings, constraints, and desires to break free, and we turn the pages eagerly to hear what river, fire, and salmon speak in return. Indeed, one feels a great interest to see where Roberts will next explore. This debut collection is the work of a highly imaginative poet, deservedly a finalist for the upcoming Gerald Lampert Award.

Al Rempel’s debut collection of poems, understories, is a gritty, multilayered, and  complex look at northern living. Rempel writes with humour, compassion, tenderness, and a range of poetic form and diction. Above all, he writes with uncompromising honesty and a desire to find and reveal the underside of things. Rather than stories of snow, these are stories of what lies hidden beneath snow. “There was evening and there was morning, the first of too many days. We knew that the wind- / chill numbers were all made up. Like the price of gas. Like the words we exchanged in bed.” (“Fretting Winter”)

complex look at northern living. Rempel writes with humour, compassion, tenderness, and a range of poetic form and diction. Above all, he writes with uncompromising honesty and a desire to find and reveal the underside of things. Rather than stories of snow, these are stories of what lies hidden beneath snow. “There was evening and there was morning, the first of too many days. We knew that the wind- / chill numbers were all made up. Like the price of gas. Like the words we exchanged in bed.” (“Fretting Winter”)

Composed of five sections—“back alleys,” “strata,” “under my skin,” “black as crows,” and “thin rain”—the book ranges from the back alleys, the hardness of community living in Prince George, to the rocks, glaciers, and mountains of the north, to tender portraits of the poet’s father, wife, and daughter, and extends outwards again into an exploration of the natural wildlife of northern forests. Here nature is not perceived as enemy or alien. On the contrary, as in these beautiful lines from “Shiver In,” the poet experiences himself deeply as part of nature:

last night I dreamt I was a birch tree

felt the sap set deep

into the marrow of my shinbones

woke up with yellow and gold

leafing open in my palms

Though at times he can be simple and meditative, as in the example above, Rempel’s characteristic style in this collection is complex, often informed by several ideas at once in a layering of images. He expects the reader to think. One of my favourite poems in the book, “thin rain” demonstrates his unusual skill as a metaphysical poet. He interweaves cosmic and microcosmic strands to reveal the “understory” of a relationship between man and woman through weather forecasts, images of rain, stars, and moon, and “two revolving bodies.” Like Donne, Rempel uses images from astrophysics to give a sharp edge to the love story, in a poem that manages to be both formally elegant and, at the same time, entirely contemporary in diction and atmosphere.

This approach underpins another of the strongest poems in the collection, “A Few Lines for Prince George.” Here, Rempel invites us to observe narrative within narrative as he presents the story of himself as a thirteen-year-old boy reading The World Book Encyclopedia. He enfolds the boy’s inner thoughts, colloquial and awkward as he approaches the article on the female reproductive system—”but there was no way I’d ask Mom,”—within the imperturbable flow of the encyclopedia’s impersonal narrative, in wonderfully sustained long lines that mimic the unstoppable flow of evolution: “every day we cut along the smooth curve and arc of ancient river benches / the maps in our heads already determined, wheels thrumming over floodplains of gravel.” The effect is both humourous and poignant. The poet moves to an unexpectedly serious conclusion as the boy reads of “a convict who gave his body over to science” and moves from images of sexuality toward images of death. Clearly, there are multiple understories.

As with most debut collections, some poems could have been omitted; several poems, such as “One Leaf,” employ too much repetition. The strongest poems in understories draw one back to many re-read-ings, offering the richness of an uncommon awareness, from a poet who is both sensual and intellectually wide awake.

—Barbara Colebrook Peace