Reviews

Poetry Reviews by Candace Fertile

Sam Cheuk, Love Figures (London: Insomniac, 2011). Paperbound, 106 pp., $14.95.

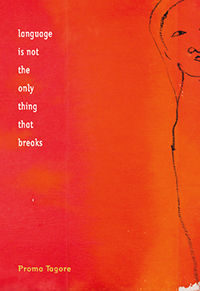

Proma Tagore, Language is not the only thing that breaks (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp, 2011). Paperbound, 72 pp., $14.95.

Ursula Vaira, And See What Happens: The Journey Poems (Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin, 2011). Paperbound, 112 pp., $16.95.

First of all, my thanks to small presses for publishing poetry, especially first collections. These three writers—Sam Cheuk, Proma Tagore, and Ursula Vaira—deserve to have their work read, and it’s often difficult to sift through numerous literary journals to find a specific writer’s work.

Sam Cheuk divides his time between Toronto, Vancouver, and New York, and his  poetry reflects a world view while focussing on the intimacy of family and romance. As the title Love Figures indicates, these poems are about love in many of its guises. In Cheuk’s poems, the emotion created is often sadness, as they tend to deal with loss or the complications of a son’s relationship with family, particularly his father. Cheuk’s collection has three parts—“Punctum,” “Love Figures,” and “I am me. / You are you”—although the book has the connective tissue of love. The first and last poems reveal a difficult relationship with the speaker’s father. In “Dramaturgy,” Cheuk imagines two conversations between father and son, one in which the answer to a question about hate is “no” and one “yes.” In a brilliant move, Cheuk takes the conversation to the next generation, and his speaker imagines his son in the same situation. The complexity of the father-son bond (both positive and negative) is finely wrought, and the duality of the bond is captured eloquently and sadly in the last line: “This is me, your child, pallbearer of our name.” That line, like so many of Cheuk’s, clenches my heart. The last poem “Epilogue 2,” returns to the father-son relationship. Here the father is a hard man punishing his child for an unspoken failure by making him sit at the dinner table alone. This poem picks up a topic travelling through much of Cheuk’s work—the power of language and of silence: “Head down in the chair, pretending for someone./ What can be redeemed must redeem in silence.” Silence figures much as love does, and knowing what to say and when to say it or say nothing is critical to Cheuk’s speakers.

poetry reflects a world view while focussing on the intimacy of family and romance. As the title Love Figures indicates, these poems are about love in many of its guises. In Cheuk’s poems, the emotion created is often sadness, as they tend to deal with loss or the complications of a son’s relationship with family, particularly his father. Cheuk’s collection has three parts—“Punctum,” “Love Figures,” and “I am me. / You are you”—although the book has the connective tissue of love. The first and last poems reveal a difficult relationship with the speaker’s father. In “Dramaturgy,” Cheuk imagines two conversations between father and son, one in which the answer to a question about hate is “no” and one “yes.” In a brilliant move, Cheuk takes the conversation to the next generation, and his speaker imagines his son in the same situation. The complexity of the father-son bond (both positive and negative) is finely wrought, and the duality of the bond is captured eloquently and sadly in the last line: “This is me, your child, pallbearer of our name.” That line, like so many of Cheuk’s, clenches my heart. The last poem “Epilogue 2,” returns to the father-son relationship. Here the father is a hard man punishing his child for an unspoken failure by making him sit at the dinner table alone. This poem picks up a topic travelling through much of Cheuk’s work—the power of language and of silence: “Head down in the chair, pretending for someone./ What can be redeemed must redeem in silence.” Silence figures much as love does, and knowing what to say and when to say it or say nothing is critical to Cheuk’s speakers.

Just as Cheuk examines the role of language, he also plays with the role of space on the page. The most successful poems are those with a more conventional structure. In a few poems with dates as the titles, Cheuk tries unusual spacing and line length, but the difficulty of reading the lines undercuts their efficacy. But these are only a handful, and when Cheuk sticks to less experimental forms (including the prose poem), he nails his subjects. The collection is stippled with fabulous lines. In “Love Letter #3: You Are Away,” the speaker questions a woman’s actions:

You don’t know where she goes

at night, housed behind her eyelids

could be a revolution, a girl smiling

in a Sunday dress, a thud.

Memory is singular—you can’t be there.

Cheuk builds masterfully to the last line of that first stanza as he does so often in this collection. Overall, the poems ask about truth, a slippery and completely engaging investigation.

Proma Tagore’s Language is not the only thing that breaks reveals its political  purposes immediately in her foreword: “I acknowledge the unceded territories of the Coast Salish people. I offer my respect and solidarity to the many Indigenous communities of India, where I was born, and Turtle Island, where I have lived for most of my life.” The predominant emotion in Tagore’s collection is anger: anger at injustice and loss. The tension of racism and homelessness is portrayed in numerous ways. The first poem, “displacement,” indicates the prevailing mood. This poem sets up the book perfectly with its description of various causes and types of displacements, including immigration, natural disaster, racism, sexism, and war. Tagore’s move from India to Canada at the age of four means she has her feet in two worlds—or possibly in neither. That’s one of the challenges of the immigrant, and for an immigrant of colour the challenge is heightened. And the difficulty is increased for women: “disappeared women / driven under dreams” makes me think of the women lost (and for a long time forgotten by the authorities from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and northern B.C.’s “Highway of Tears.” The second poem, “warzones,” combines the disaster of Gaza and Vancouver’s troubled area:

purposes immediately in her foreword: “I acknowledge the unceded territories of the Coast Salish people. I offer my respect and solidarity to the many Indigenous communities of India, where I was born, and Turtle Island, where I have lived for most of my life.” The predominant emotion in Tagore’s collection is anger: anger at injustice and loss. The tension of racism and homelessness is portrayed in numerous ways. The first poem, “displacement,” indicates the prevailing mood. This poem sets up the book perfectly with its description of various causes and types of displacements, including immigration, natural disaster, racism, sexism, and war. Tagore’s move from India to Canada at the age of four means she has her feet in two worlds—or possibly in neither. That’s one of the challenges of the immigrant, and for an immigrant of colour the challenge is heightened. And the difficulty is increased for women: “disappeared women / driven under dreams” makes me think of the women lost (and for a long time forgotten by the authorities from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and northern B.C.’s “Highway of Tears.” The second poem, “warzones,” combines the disaster of Gaza and Vancouver’s troubled area:

January is a brutal winter cold stormwinds strike the city hit

in Gaza, the air hangs heavy with clouds of phosphorous death

This poem is one of the few in which Tagore uses capitals; generally the poems are all lower case, presumably a levelling factor in the hegemony of words. These poems are devastating in their criticism of all the things human beings have done wrong to fellow human beings and to the planet. Everything breaks, including language, but most sorrowful is the breaking of human hope. Small glimmers of possibility exist in a few poems. In “repair,” for example, a four-line prose poem, Tagore ends with “i ask how we got here, you ask about tomorrow.” The future is always a question, but to think about the future presumes there will be one—and thus the question includes some hope.

Ursula Vaira’s And See What Happens: The Journey Poems offers three stories of  journeys. The first, “And See What Happens,” recounts in various forms Vaira’s participation in “Journeys ’97,” an RCMP-First Nations 1000-mile paddle from Hazelton, B.C., to Victoria. Led by Roy Henry Vickers, the journey’s purpose was to apologize to First Nations communities for the tragic legacy of residential schools and to raise awareness of the problem of addictions. Vaira, a Caucasian civilian, was the only woman taking part. These poems combine sorrow and a gentle humour to delineate the tragedies of the past and their ongoing grievous effects. In “Teacher, visionary, healer, warrior,” a prose poem, Vaira pays homage to Vickers, who “dreamed of joining the RCMP but was turned down because he was colour-blind. So, he became an artist.” This poem also points out that most policing in Canada is in response to the consequences of addictions, so Vickers’ dream of having an addictions recovery centre for addicts of any background makes sense. The first journey has several light moments. In “How many embraces can a humble man endure?” Vaira describes the dismay some residential-school survivors have when the group lands, the dancing (the police paddlers are called “Butterflies” as they have no nation), and then the tears of the officers, who “are completely undone.” The light comes in with the children who have “sweet-talked [the RCMP] / into letting them wear their Stetsons. / Trays of dessert come around, and come around / and come around again, offered by children / who will not take no for an answer.” The balance is exquisite. The second journey is called “Frog River,” where, in seventeen ghazals, Vaira describes the trip and an emotional separation. She is on the river; her partner is at home. She stays in a basic cabin in cold weather, and the physical challenge of being in the wilderness mirrors the challenge of love. The poems ask which experience is more dangerous. In “VII,” she notes: “I fish all day for one fish. / I am learning the meaning of desire.” Because of the two-line stanzas, the form juxtaposes the issues in the speaker’s life—the physical survival and the emotional. The third journey, “Last One to Get There,” is about kayaking for twenty-two days around the north end of Vancouver Island. All the poems (with place names for titles) have seven lines except “Goletas,” about missing a pod of whales. Vaira combines form and content beautifully, and her similes are splendid: “Once again we paddle along shore like ducklings following Glenn.”

journeys. The first, “And See What Happens,” recounts in various forms Vaira’s participation in “Journeys ’97,” an RCMP-First Nations 1000-mile paddle from Hazelton, B.C., to Victoria. Led by Roy Henry Vickers, the journey’s purpose was to apologize to First Nations communities for the tragic legacy of residential schools and to raise awareness of the problem of addictions. Vaira, a Caucasian civilian, was the only woman taking part. These poems combine sorrow and a gentle humour to delineate the tragedies of the past and their ongoing grievous effects. In “Teacher, visionary, healer, warrior,” a prose poem, Vaira pays homage to Vickers, who “dreamed of joining the RCMP but was turned down because he was colour-blind. So, he became an artist.” This poem also points out that most policing in Canada is in response to the consequences of addictions, so Vickers’ dream of having an addictions recovery centre for addicts of any background makes sense. The first journey has several light moments. In “How many embraces can a humble man endure?” Vaira describes the dismay some residential-school survivors have when the group lands, the dancing (the police paddlers are called “Butterflies” as they have no nation), and then the tears of the officers, who “are completely undone.” The light comes in with the children who have “sweet-talked [the RCMP] / into letting them wear their Stetsons. / Trays of dessert come around, and come around / and come around again, offered by children / who will not take no for an answer.” The balance is exquisite. The second journey is called “Frog River,” where, in seventeen ghazals, Vaira describes the trip and an emotional separation. She is on the river; her partner is at home. She stays in a basic cabin in cold weather, and the physical challenge of being in the wilderness mirrors the challenge of love. The poems ask which experience is more dangerous. In “VII,” she notes: “I fish all day for one fish. / I am learning the meaning of desire.” Because of the two-line stanzas, the form juxtaposes the issues in the speaker’s life—the physical survival and the emotional. The third journey, “Last One to Get There,” is about kayaking for twenty-two days around the north end of Vancouver Island. All the poems (with place names for titles) have seven lines except “Goletas,” about missing a pod of whales. Vaira combines form and content beautifully, and her similes are splendid: “Once again we paddle along shore like ducklings following Glenn.”

Three first collections: three wonderful collections. Please keep them coming, poets and small presses!

—Candice Fertile