Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Cara-Lyn Morgan

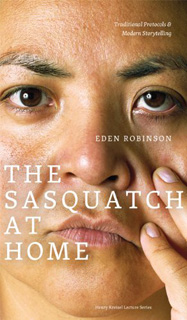

Eden Robinson, The Sasquatch At Home (Edmonton: University of Alberta & Canadian Literature Centre, 2011). Paperbound, 50 pp., $16.

This compilation of lectures given by storyteller and author Eden Robinson at the 2010 Canadian Literature Centre’s Henry Kriesel Lecture Series, when bound and printed, maintains the inherent qualities of good poetry, biography, as well as the truly wonderful storytelling abilities for which Robinson is known. Together in book form, the lectures become a unique gathering of quirky family vignettes that reach outside the intimacies of a single family and delve into the more complex dynamics of the community. Robinson looks at the politics of naming within the Haisla tradition, the ownership of stories, and the desire to preserve oral traditions through the acts of writing and telling stories.

She begins with a comic pilgrimage to Graceland, the Memphis home of the late Elvis Presley, and the one place in the world where Robinson’s mother has always wanted to visit. As daughter and mother meander through the chintz of Graceland, Robinson comes to realize how a place that means so much to her mother can evolve, for her, from a tourist trap into a place of reverence and wonder “… as we walked through the house and she touched the walls, everything had a story, a history. In each story was everything she valued and loved and wanted me to remember and carry with me. This is nusa.” Nusa, is described as the way traditional thinking and cultural protocols are passed through generations of Haisla people. It is a complex concept that Robinson masterfully explains against the strange backdrop of the Presley manor, in the awed presence of a true Elvis fan. “You should never go to Graceland without an Elvis fan,” Robinson writes. “It’s like Christmas without kids—you lose that sense of wonder.”

This ability to present complicated cultural elements while remaining inclusive, is part of the charm of this small book. As we move from Graceland to the stony beaches of the northwest coast, Robinson narrows in on the slow-swimming oolichan, a local fish, to show how tradition on a larger level is becoming lost between generations. The once abundant oolichan was a dietary staple for the Haisla community, arriving late in the year once the food stores had been consumed. She describes waiting for the oolichans with her father on a blustery day, and how, when they did not arrive, being forced to trade for someone else’s less appealing catch. With the depletion of the oolichans the community risks losing more than just a food source. “If the oolichans don’t return to our rivers, we lose more than a species. We lose a connection with our history, a thread of tradition that ties us to this particular piece of the Earth, that ties our ancestors to our children.”

Throughout the lectures, Robinson explores the act of conserving tradition through writing, while attempting to avoid the apparent betrayal of closely protected family and community stories. She recalls writing her first novel: “I knew I couldn’t use any of the clan stories—these are owned by either individuals or families and require permission and a feast in order to be published.” Some stories, however, are considered publicly owned and could be published as long as they contain “no information people felt uncomfortable sharing with outsiders, such as spiritual or cultural content.” She would have to learn which stories could be safely told and which would need to be kept within the community alone. It is not an easy task to be a writer of family stories. There are always elements that need to be withheld in order to respect the peace of the family and community and it is the task of the storyteller to decide how far boundaries can be pressed. These lectures, therefore, have an intrinsic withholding quality woven through, a feeling that as an “outsider” I would be privy to only so much. Robinson somehow avoids a feeling of us-versus-them alienation through her use of bright humour and the universality of family stories. She strikes sweetly at the commonality of people rather than narrowing in on cultural differences. The entire book is fast, colloquial, and engaging; concise enough to be read in one sitting, yet retaining the weightiness of a larger work. Its brevity makes it an ideal re-read and the second reading proves just as entertaining. The funny parts remain funny, the rendering of landscapes evocative and intimate, and the general themes stay relevant. Through rich and often comic dialogue and her painterly descriptions of the northwest landscape, Eden Robinson presents a glimpse into her community with the delicious, whispered quality of a well-told, yet well- protected, family story.

—Cara-Lyn Morgan