Reviews

Fiction Review by Allison Lasorda

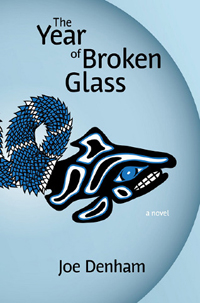

Joe Denham, The Year of Broken Glass (Gibsons: Nightwood, 2011). Paperbound, 327 pp., $24.95.

The protagonist of Joe Denham’s debut novel is presented to the reader

amidst complex and devastating circumstances. Francis Wishbone is a

B.C. crab fisherman who divides himself and his time between two

women and their respective children. The setting is a landscape of

uncertainty; distressing changes to the environment and the fishing

industry remain a thread that ties the characters together. This thread

is made significant by the unexpected and strange mythology Francis

is forced to contemplate after discovering a glass fishing float that,

allegedly, was significant to an ancient society. “[It] is said that until the

float is found, broken and cast into the mountain, the oceans will be

caught in the throes of an exponential extinction crisis that will eventually

threaten the very ability of humans to survive on earth.”

The protagonist of Joe Denham’s debut novel is presented to the reader

amidst complex and devastating circumstances. Francis Wishbone is a

B.C. crab fisherman who divides himself and his time between two

women and their respective children. The setting is a landscape of

uncertainty; distressing changes to the environment and the fishing

industry remain a thread that ties the characters together. This thread

is made significant by the unexpected and strange mythology Francis

is forced to contemplate after discovering a glass fishing float that,

allegedly, was significant to an ancient society. “[It] is said that until the

float is found, broken and cast into the mountain, the oceans will be

caught in the throes of an exponential extinction crisis that will eventually

threaten the very ability of humans to survive on earth.”

If this synopsis seems overwhelming, it is—both for the book’s main characters and for the reader. Yet this highly dramatic plot is gracefully slowed with Francis’s lengthy boat journey to Hawaii, where he hopes to sell the float to a high-paying collector. On the open ocean, away from relationship problems and environmental degradation, Francis self-reflects and confronts dispiritedness and hope. These feelings stir him to reference such oceanic literary giants as Melville and Coleridge. Denham’s narrative perhaps strives to place the reader as The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’s Wedding Guest, as we oscillate between bemusement and impatience, anxiety and fascination. Along for this journey is Miriam, a calm, older woman whose presence seems to bring out what goodness is left in Francis. She gains insight into his “old-fashioned romantic” nature, which, until this point in the novel, has come across as simple naiveté. Back onshore, Francis is living multiple lives; he has a wife and son, a mistress and infant daughter, and an intense history as an alcoholic. The ocean, then, often “flat as glass,” provides an endless mirror, into which Francis often stares, becoming absorbed by the motivations and failings of his psyche. Rather than finding this a destructive process, Francis is ultimately “reawakened…to love’s potential, to its true essence… which has cast [him] into a state of divergent clarity and confusion.”

Aside from the superbly educated environmental opinions and arguments of its characters, this novel centers on the possibility of the supernatural and the grace of survival. When Francis becomes stranded at sea, in the worst of circumstances, he begins to think of a distant power; “god—whatever that is” seems to be at the forefront of his mind, and the nature of this god understandably shifts in accordance with his moods: at times angry, merciful, or nonexistent. “There’s nothing out there. Francis can feel it, the vast emptiness of the air around him. If there are gods, or a God, they’re not with him now…And then he thinks further, for the first time in weeks, beyond his immediate predicament.” While Francis claims to be aware of, even confident in, God’s absence, this seems incongruous for a man who so clearly displays the qualities of one who is practising the suspension of disbelief. In Biographia Literaria, Coleridge states that he wrote the Lyrical Ballads “so as to transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.”

Though Francis is overwhelmed by his own mortality and subsequent helplessness while he is drifting, once rescued, he is again consumed by the glass float that led him into tragedy and that remains eerily unbroken. As he goes through the motions of normal life, his wife senses that Francis is haunted by his experiences, and watches his personality transform with what she sees as obsession: “Nothing can bring back what’s died from the world.… Not the breaking of any magic antique fishing float. I have no way of explaining why it won’t break. But to take it as evidence of some mystical prophecy is a leap of faith, and it’s that faith that Francis is clinging to now.” To those around him, Francis may appear to be either caught inside his imagination or seeing the world in a truer, more meaningful way, something the narrative leaves delicately unclear. The exploration of human limitation, especially in terms of our understanding of the supernatural, is relevant for the confusing tumult of The Year of Broken Glass, and raises interesting questions that readers can apply to contemporary issues of personal and environmental uncertainty.

—Allison Lasorda