Reviews

Poetry Review by George McWhirter

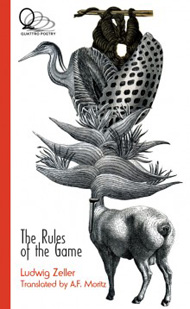

Ludwig Zeller, The Rules of the Game, translated by A. F. Moritz (Toronto: Quattro, 2013). Paperbound, 150 pp., $16.95.

Since The Rules of the Game has no Spanish en face, we can only read the poet via his translator’s embodiment. Happily, three decades of closeness between poet and translator has let this assumption of one (Zeller) by the other (Moritz) happen.

Since The Rules of the Game has no Spanish en face, we can only read the poet via his translator’s embodiment. Happily, three decades of closeness between poet and translator has let this assumption of one (Zeller) by the other (Moritz) happen.

In his lifetime, between Chile, Mexico, and Canada, Ludwig Zeller has espoused, divorced, and remarried surrealism, but I’d dub the man a metaphysical, once removed. He yolks his heterogeneous ideas and natural phenomena together, not only with violence, but with affinity and beauty—and a large, puckish portion of wit: “My mother gave me a candle, so I could light it and hear the wick of her laughter” (“Remembering in the Wax”). A quick synesthesia, yes, but it cuts to the quick of his mother’s influence. For straighter, more literary memento mori, there’s “The Locket of the Bronté Sisters,” found in the station where the sisters waited for the impossible lover, who never came. Zeller doesn’t understand why. His assumption: everyone loves the Brontés. The piece is pure Masterpiece Theatre. These two examples demonstrate the scope of Ludwig Zeller’s art, but what of his themes, his obsessions? The book opens with poems for the four elements and previews of the Ludwig Zeller perpetual polarities. In “Water,” “the sands that swallowed my days” are set against “the mysterious current that engrossed my childhood… / Sea of freedom, sky-earth, heaven-earth, wandering / mirror in which we enchant ourselves.” Those sods of paradise were laid down in a garden, close to the Atacama desert, where Zeller hails from. The pain of that loss endures “crying out, in love, tenacious….” For him, everything is split in two by this and by Chile’s great national trauma. “The Acrobats” he watches perform in memory—he hears their image leap from that mirror— and “the thunder of drums, full of sun,” also represent a lost generation, citizens of Chile in a human pyramid, “a tower held on one foot.” Or under one—Pinochet’s? When Zeller himself leaps into the act at the finale, “harpoon in his teeth,” he spears both the past and the decimators of his kind.

Returning to his art—in “A Dove Dreamed,” he asks for “bird-song your eternal leaves / Your secret plumage,” and this shapes how the wings on his words behave, as animate and prolific as the fowl they follow, and the flora. But are his fusions of ideas and things merely forced effects, surreal contrivances? Is there any physical base in the world for what he hears, feels, smells, or sees? Take the opening stanza of “To the One Who Watches Will Everything Be Revealed”: “Wind breathes in the steep vertical solitudes / Where birds that constantly open the veins of night / Strike and light their phosphorous heads on a knife edge.” A reviewer might poke a poor pun at this and deem the phenomena in the stanza more striking than real. But bright (white-dove) birds do strike, and come alight like phosphor in water, or matches when they plunge into the oncoming dark. Grit and grandeur go together with Zeller’s (resident) grief. At the end, “The dove isn’t coming back / Ashes grow quiet in the courtyards of the ark.”

Throughout, the book is punctuated by outcriers, where grief and pain find no fine form to inhabit, where the dementias of displacement and loss are voiced raw. Also, peregrinating through the pages, there’s the ever-ambiguous, ineluctable she. Early, and momentarily, she appears in his “childhood song,” in the elemental poem, “Water”: “song / of a woman straying toward the desert,” and later in “If She Came Back”: “on the roads with her fabulous merchandise,” a wandering cornucopia, who descends into the boredom of stone if she is made a fixed object of worship. Staying true to her means to stray and multiply: “Would we want to cease / Dreaming larvae like ladies with automatic teeth?” A senseless image statement, perhaps, but I go along with it and Ludwig Zeller. Oh, says I, to go on hatching, in rows, the sharks teeth of sharp similes and similarities! And yet, this she has crows who sing and “their cages, already sitting at the lowest depth / Have floors that are mouths of bottomless wells.”

Who is this she of the fabulous merchandise and crows? Ludwig Zeller’s verse, his lover, his “motionless river of frankincense” (“Listening to Venus”), his soul—crossing into otherness (“Preferring a Dream”), “a butterfly of warmth, fluttering across the moon in mirrors / Of pleasure…”? In “The Eyewitness,” the eye deep in the canvas of the painting looks into the poet’s “through the other” (person/soul/or ineffable other?). Zeller’s enduring double dimensions, his twoness of being here and there, in the snow-North (Ontario) or sand-desert-South (the Atacama), being himself and something else may haunt him; however, his door of metaphor to these intangible dimensions I most enjoy is opened in class by “Father Gregorio” (“A Maker of Infernos”) to teach his “forty rascals” the mechanisms of eternity and hell. Then, the father’s (and Zeller’s) metaphysical casuistry is a delight.

I commend Al Moritz, whose agility and ability has brought these linguistic somersaults into English. Not once did I think this must be missing something from the original. I felt fully satisfied, throughout.

—George McWhirter