Reviews

Fiction Review by Theresa Kishkan

Gillian Wigmore, Grayling (Salt Spring Island: Mother Tongue, 2014). Paperbound, 114 pp., $16.95.

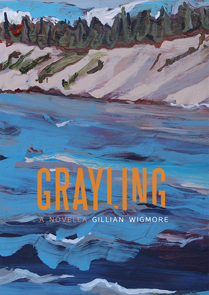

Consider the novella. For decades the form enjoyed respectability, a place of honour on the lists of many publishers. No one apologized for the brevity of, oh, Death in Venice or The Ballad of the Sad Cafe. Few lamented that a novella wasn’t as lengthy and complicated as War and Peace, that the printed volume didn’t include a family tree spanning centuries. The contemporary European literary tradition includes the novella as a matter of common sense: I think of the Peirene Press and Sylph Editions with their devotion to the marriage between text and design. There’s been a fair amount of spirited debate about the parameters of the novella. It’s generally agreed that the optimum length is somewhere between 20,000 and 40,000 words, but there are exceptions. I’d argue that James Joyce’s The Dead is a novella, though at roughly 15,000 words, it’s short. Still, it has the dramatic tension, the scope, the unity of place and subject, and its language is beautifully condensed and elliptical—all qualities I associate with the form. In 2012, Ian McEwan wrote (in The New Yorker), “I believe the novella is the perfect form of prose fiction. It is the beautiful daughter of a rambling, bloated ill-shaven giant (but a giant who’s a genius on his best days).” Thirteen years ago I published a novella with a small Canadian publisher willing to include it on a list with several other novellas, printed as small books and priced accordingly. Recently I was told that, alas, a novella is no longer a viable form to market in today’s economic climate. So I was delighted to receive a copy of Gillian Wigmore’s Grayling, with its gorgeous cover (by Annerose Georgeson) and French flaps enclosing a book perfectly sized to suit its contents. The publisher makes no apologies (and honestly, why should she? Do presses make excuses for slim collections of poetry?), but instead celebrates the form.

on the lists of many publishers. No one apologized for the brevity of, oh, Death in Venice or The Ballad of the Sad Cafe. Few lamented that a novella wasn’t as lengthy and complicated as War and Peace, that the printed volume didn’t include a family tree spanning centuries. The contemporary European literary tradition includes the novella as a matter of common sense: I think of the Peirene Press and Sylph Editions with their devotion to the marriage between text and design. There’s been a fair amount of spirited debate about the parameters of the novella. It’s generally agreed that the optimum length is somewhere between 20,000 and 40,000 words, but there are exceptions. I’d argue that James Joyce’s The Dead is a novella, though at roughly 15,000 words, it’s short. Still, it has the dramatic tension, the scope, the unity of place and subject, and its language is beautifully condensed and elliptical—all qualities I associate with the form. In 2012, Ian McEwan wrote (in The New Yorker), “I believe the novella is the perfect form of prose fiction. It is the beautiful daughter of a rambling, bloated ill-shaven giant (but a giant who’s a genius on his best days).” Thirteen years ago I published a novella with a small Canadian publisher willing to include it on a list with several other novellas, printed as small books and priced accordingly. Recently I was told that, alas, a novella is no longer a viable form to market in today’s economic climate. So I was delighted to receive a copy of Gillian Wigmore’s Grayling, with its gorgeous cover (by Annerose Georgeson) and French flaps enclosing a book perfectly sized to suit its contents. The publisher makes no apologies (and honestly, why should she? Do presses make excuses for slim collections of poetry?), but instead celebrates the form.

Grayling’s narrative is closely located within a specific landscape—northern British Columbia, near the Yukon border. The protagonist, Jay, has driven to a remote area along the Cassiar Highway in order to put his canoe into the Dease River; he is planning to paddle for several days to Lower Post where his truck will be waiting. With some hastily assembled gear and a single lesson on a parking lot, he hopes to fly-fish for grayling, a species of freshwater fish belonging to the salmon family, and native to the Arctic and Pacific drainages. Tiny graphic images of these fish swim along the lower pages of the novella, to remind us where we are and what we should be alert to.

The Dease is liminal space for Jay. Having recently undergone surgery for a testicular tumour, he is also recovering from a broken relationship. He has given up his job and his home. His journey down the river is intended to bring him not only to Lower Post but also to a new way of living. The river is a threshold, a crossing. He experiences it in his body as a pulse, a rhythm. “His mind went ahead, trying to imagine the current and the obstacles and the rapids he would encounter. His heart felt raw, beating harder than it should for the effort he exerted pulling the water and pushing the paddle forward through the air.”

When Julie pulls Jay from the canoe at a primitive campsite and warms his hypothermic body, the reader is as surprised as Jay. Who is she and how did she arrive in such a far-flung place? When she joins him on the river, she unsettles his balance. As she pulls one prize after another from her pack—wine, cheese, basil, fresh noodles, and even a bottle of single-malt—and engages Jay in discussions of Leonard Cohen’s song “Suzanne,” it becomes increasingly clear that she is as mythic as the woman in that song. No tea and oranges, but coffee and croissants, and a perfectly ripe cantaloupe are brought from the bottom of her packsack. (“She lets the river answer that you’ve always been her lover....”) And of course there are the grayling, which Julie, who has never fished before, keeps pulling from the river and which Jay ties to the painter for a future dinner. “They’re beautiful—silver and blue and iridescent—and they have a tall dorsal fin that stretches out like a sail.”

Grayling begs for a map, perhaps printed on the endpapers, so that the reader wouldn’t have to balance a road atlas on a lap while reading. You want to follow the journey, tracing your finger across the blue scribble of river, pausing at certain turns. Here’s the Dease River Resort; this must be French Creek. This novella is riparian: “the hum of cicadas in the heat...red-winged blackbirds in the marsh,” and that small scribble of grayling swimming along the bottom of each page. And Grayling is a poet’s novella, written with the care and attention a fine writer brings to language, to timing, and to the unfolding of story across a wild terrain. Even its cryptic conclusion—those wolf-tracks mingling with human footprints; Julie’s packsack emptied of its surprises—is satisfying, in the way a poem can continue to play in the mind long after one puts it aside: a grayling on a hook, spinning the river’s length.

—Theresa Kishkan