Reviews

Fiction Review by Trevor Corkum

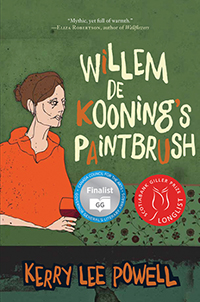

Kerry-Lee Powell, Willem De Kooning’s Paintbrush (Toronto: Harper Collins, 2016). Paperbound, 252 pp., $21.99.

There are short-story debuts that emerge into the world and merely hint at the promise to come. Then there are collections that arrive fully formed, as if the writer is no mere debutante, but has stepped directly into the literary spotlight, with an ace or two (or three) up her sleeve. The latter would describe Kerry Lee-Powell’s first collection, Willem De Kooning’s Paintbrush. The only book of fiction to find favour with all three juries for Canada’s major fiction prizes in 2016 (longlisted for the Giller; shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award and the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize), Powell’s eclectic suite of stories garnered strong buzz and sustained critical acclaim throughout the fall literary season.

There are short-story debuts that emerge into the world and merely hint at the promise to come. Then there are collections that arrive fully formed, as if the writer is no mere debutante, but has stepped directly into the literary spotlight, with an ace or two (or three) up her sleeve. The latter would describe Kerry Lee-Powell’s first collection, Willem De Kooning’s Paintbrush. The only book of fiction to find favour with all three juries for Canada’s major fiction prizes in 2016 (longlisted for the Giller; shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award and the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize), Powell’s eclectic suite of stories garnered strong buzz and sustained critical acclaim throughout the fall literary season.

In part, Powell’s own personal trajectory lends the collection its peripatetic feel. Born in Montreal, she has lived in Australia, Antigua, the United Kingdom, and across Canada. Ranging in locations as far afield as London, small-town Canada, and an unnamed Caribbean island, these fifteen stories explore the lives of a broad cast of characters—an impromptu bartender in the midst of her dizzying first gig; a delusional suburban teen; a stripper; a grim bride-to-be—who, more often than not, find themselves paralyzed by the grim inertia of their lives. As a whole, the work feels like a sustained study in transience, exploring with compassion and precision the urge many of us secretly harbour to escape the predicable plotline of our lives. Some of Powell’s characters manage this willful disappearance with ease; others remain rooted in place against their will. The act of escape itself, however, in a Powellian landscape, does not necessarily render healing, or absolve her men and women of the claustrophobic fears and unruly desires that clatter like bogeymen through the dusty rooms of their brains. Running away merely keeps the acute pain of being alive temporarily at bay.

Take one of the collection’s many standouts, “There Are Two Pools You May Drink From.” Here, a middle-aged narrator hunts down a long-lost childhood friend, Lindy Moon. “My childhood friends have all disappeared. People die or get unlisted numbers. Some people don’t want to be found. I have moved from place to place all my life, and the only time I ever looked back was to make sure nobody was following. Lately, however, even moving hasn’t done the trick, and I’ve given up on the idea that there’s a mythical place where I’ll find everlasting happiness.” When she turns up at Lindy’s home unannounced, hoping to revisit the traumatic past they share, the narrator is disappointed (though not surprised) by the veil of cloistered amnesia through which Lindy now interprets her life. “But looking at Lindy I see for a moment, as if through a chink in a stone wall, how it is possible to keep steady while the hands travel across the clock’s face, how the smallest variations in the yard might give comfort as the years pass, why children beg to be told the same story again and again.” Elsewhere, Powell’s shape-shifting, versatile prose takes centre stage. At times vaudevillian, subdued, quirky, even grotesque, Powell has a knack for grinding the most vital emotional nutrients from the rock salt of her language.

In the collection’s stellar opener, “In a Kingdom Beneath the Sea,” an ambitious young stripper performs in a decrepit, small-town hotel. Powell packs off-key humour and restrained pathos into a few acrobatic lines. Her cadence is perfect:

When I finally made up my mind to become a stripper, I made a mix-tape of songs and worked out a routine in the basement storage room. The songs sounded all wrong when I finally climbed onstage a few weeks later. I thought at first it was nerves, but the tape was damaged. I got lost in the distortions, and all the walls and faces wavered in the semi-darkness while part of me watched from on high as Helen Blackmore, former member of the First Baptist Church choir, winner of the Calvary Education Centre inter-school spell-a-thon, transformed herself into a naked trembling creature with jellyfish legs.

In a few instances, the aerodynamics of language cause the stories themselves to sag. In “Vulnerable Adults”—a study in the slow decay of a stale relationship—the zingers and glib observations of Lauren and her puppet-making boyfriend, Jacko, occasionally feel forced. Witticisms overlay one another, piling on, until it’s difficult to fathom or divine any genuine spark of attraction between the pair. The lovers are method actors, performing for the reader as they sashay across the page. While perhaps intended, with little in the way of plot, this reliance on the performance of language renders the tale a muted character study.

In an essay in Quill & Quire, Powell takes issue with the obligatory and inevitable comparisons to Alice Munro many emerging Canadian short-story writers find thrust upon them. “I worry that our casual use of the phrase “the next Alice Munro” speaks more to a studious insularity than a true appreciation of her art….To be like Munro is to be paradoxically “unlike” Munro. I can’t think of another author who is so quietly, defiantly herself, delving again and again into the same subjects, the same landscapes, the same themes. She is able to refashion these materials into something new and compelling, a testament to her evolution as an artist.” Indeed, while the emotional vigilance and sheer intelligence of Powell’s work finds kinship with Munro, or William Trevor, its dark, off-kilter humour has much in common with the early work of Lorrie Moore. Certain stories—“In a Kingdom Beneath The Sea,” but also the book’s devastating closer, “Right or Wrong,” which finds two backwoods brothers returning home to tend to their dying stepfather—bring to mind the work of another talented debut author, Kris Bertin (Bad Things Happen), with their noir-ish explorations of rural life. Willem De Kooning’s Paintbrush, however,is the work of an original, a compassionate collection that invites readers to confront our existential distance from one another, the ways we attempt to outrun the slippery truth of our aloneness, the ghosts of our private suffering. It’s a successful, celebratory first book that surely marks the start of an exceptional career.

—Trevor Corkum