Reviews

Poetry Review by Heather Jessup

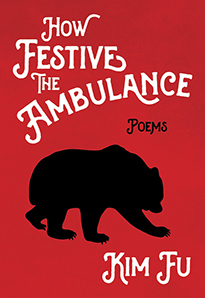

Kim Fu, How Festive The Ambulance (Gibsons: Nightwood, 2016). Paperbound, 95 pp., $18.95.

I’ve been looking forward to Kim Fu’s debut poetry collection How Festive the Ambulance since reading her debut novel For Now I Am a Boy. Her prose and dialogue are photographic in that novel. Her characters are throbbing bodies you can practically touch on each brutal page. How Festive the Ambulance has some of that same tenderness and intensity, but this time through folkloric images of pig men, mermaid sisters, a mole woman, and a unicorn princess who “plays pretend at the bridal shop.” There are lines and images in this collection that I want to keep tucked in a velvet bag to turn over, alone, at a shy table in a café. At the mole woman’s wedding, for instance, her hands are in “dirt-scoop formation” and her nails have “grown long and hard and yellow / as curls of cold butter.” This, to me, is the strangest and most perfect metaphor for that tiny curve of claw. The earth where the mole woman lives is “of a black forest cake, spongy peat,” evoking a dream we all may well have had as children that the Black Forest could be the one hopeful place in the world that is truly made of cherries and chocolate. Yet, the sweetness of such childish possibilities is dramatically curtailed in Fu’s lyrical miniatures. There are few happy endings to be found. There is death and illness. There is destruction and untethering. Even the mole-woman’s marriage ceremony ends with the gouging out of her eyes.

I’ve been looking forward to Kim Fu’s debut poetry collection How Festive the Ambulance since reading her debut novel For Now I Am a Boy. Her prose and dialogue are photographic in that novel. Her characters are throbbing bodies you can practically touch on each brutal page. How Festive the Ambulance has some of that same tenderness and intensity, but this time through folkloric images of pig men, mermaid sisters, a mole woman, and a unicorn princess who “plays pretend at the bridal shop.” There are lines and images in this collection that I want to keep tucked in a velvet bag to turn over, alone, at a shy table in a café. At the mole woman’s wedding, for instance, her hands are in “dirt-scoop formation” and her nails have “grown long and hard and yellow / as curls of cold butter.” This, to me, is the strangest and most perfect metaphor for that tiny curve of claw. The earth where the mole woman lives is “of a black forest cake, spongy peat,” evoking a dream we all may well have had as children that the Black Forest could be the one hopeful place in the world that is truly made of cherries and chocolate. Yet, the sweetness of such childish possibilities is dramatically curtailed in Fu’s lyrical miniatures. There are few happy endings to be found. There is death and illness. There is destruction and untethering. Even the mole-woman’s marriage ceremony ends with the gouging out of her eyes.

The poems in Fu’s collection mock the covers of women’s magazines, celebrate the sisterhood of true friendship, and the title poem somehow brings optimism to the peeling sound of an ambulance’s alarm: “sweet confirmation: not-dead, not-dead, not-dead.” Living close to a hospital, I have only heard direness in the siren, now, because of Fu’s line, I hear a hanging-on and a hope. In the poem “La Traviata,” we are given a “backlit panorama of blue sky and treetops” before we realize, through Fu’s clever use of the line break, that these images are not real. This simulacrum sky is “on the ceiling above the MRI machine.” Whoever lies in the machine—the poet herself, the reader, a father?—listens to opera on sanitized headphones. As the beloved you’s vitality fades with illness, the speaker gains power. She can turn up the music, “to make it swell in the chorus: In questo paradiso ne scopra il nuovo di / Let the new day find us in this paradise.” The speaker can change the weather: “I can make the sky spread over the tiles…I can make the thin fluorescent filaments / into a near and beloved star.” But, despite such omnipotence, the poem concludes with heights of imagination crashing into reality. The tragedy of opera and elegy assemble in the drudgery of procedures: “I am a limited god. I can turn hospital linens / to field grass and wildflowers; / I can bring your body to rest / in any heaven I desire. / I cannot bring you back.” This concrete vulnerability in Fu’s poetry, as in her fiction, is what I deeply admire.

Yet, for much of the collection, the poems read as though they are inside jokes or personal references that do not speak, in their enigmatic particularity, to a readership beyond a workshop or a close enclave of friends. Why does Batman get given a butter knife to defeat The Joker? Why does a speaker teach the objects of the house to talk? What does this animation do in the poem? What am I to take from this personification if I don’t regard the house, or the speaker, by poem’s end, with any further empathy? Why use these tools of poetry to alienate the reader from her world, rather than spark a new way of looking? Or, as in “Dear Rachel, I Borrowed Your Car” (here it is in its entirety): “Dear Rachel, / I’m sorry. / We took her out back, / sang her some songs, / put her in neutral / and watched her roll off the pier.” Why mimic an imagist form or a poet’s style—such as William Carlos Williams’ “This is Just to Say,” so readily evoked here—if the poet is not intentional and inventive in the allusive conversation? For instance, for such a short poem, what a misstep this title is. Why not begin the poem, as Williams does (or Pound in “In a Station of the Metro”) with the title doing some serious work? The poem’s pointless malice bruises less than Williams’ sweet and cold note about plums. Who comprises this group ganging up on Rachel? What sort of jerk borrows an acquaintance’s car only to deliberately destroy it? And, more to the point, why as a reader should I care?

There is a persistence in Fu’s poetry to list, itemize, and take stock. This form suits certain concerns of the collection—such as the various ways we dress ourselves, conceal ourselves, and modify ourselves to meet society’s expectations—but in other poems the accrual can lead to a confusion, and ultimately a resentment, rather than a kind of clarity or persuasion. Because I have fallen in love with Fu’s strange fairy tale characters of pig men and mermaids and mole wives, and because her images of hospitals and the reluctant technology of dying are haunting and effective, I want the rest of the collection to hum with Fu’s full capacity for precision, whimsy, and dark revelation.—Heather Jessup