Reviews

Poetry Review by June Halliday

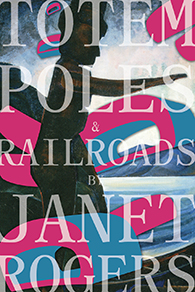

Janet Rogers, Totem Poles and Railroads (Winnipeg: ARP Books, 2016). Paperbound, 168 pp., $18.95.

Up in the air, closer to Creator, seemed to be the perfect place to experience Janet Rogers’ latest collection of poems. I voyaged through Totem Poles and Railroads on a return flight from the West Coast to Sin City for a dear friend’s wedding. After ascending into the atmosphere, I pulled the book from the seat pocket in front of me. As many Canadians will, I immediately recognized both Emily Carr and Sonny Assu’s work—Assu’s graffiti-esque formline juxtaposed upon Carr’s silhouetted welcome pole—in a “digital intervention” called We Come To Witness. The visually striking cover invites the reader into the fray of the ceremony. As the title suggests, much of the book addresses the dark corners of Canada’s history.

Up in the air, closer to Creator, seemed to be the perfect place to experience Janet Rogers’ latest collection of poems. I voyaged through Totem Poles and Railroads on a return flight from the West Coast to Sin City for a dear friend’s wedding. After ascending into the atmosphere, I pulled the book from the seat pocket in front of me. As many Canadians will, I immediately recognized both Emily Carr and Sonny Assu’s work—Assu’s graffiti-esque formline juxtaposed upon Carr’s silhouetted welcome pole—in a “digital intervention” called We Come To Witness. The visually striking cover invites the reader into the fray of the ceremony. As the title suggests, much of the book addresses the dark corners of Canada’s history.

Totem Poles and Railroads consists of thirty-six poems on numberless pages, which alternate between black and white backgrounds with contrasting lettering reminiscent of historical photographs (and their negatives). Artfully typeset text (primarily lower case) and all caps titles add to the whispered shout of the poems. Bold swathes of empty space leave room for the silence between words. In his back cover blurb, Gregory Scofield refers to the poems as “formidable winged” blackbirds “whose eyes allow us the vision we so often cannot see ourselves.” As I read, we soared over lush greenery, unceded territory, cascading mountains, invisible borders, Lewis and Clark’s serpentine trail, reservations, lakes, red rock and desert, leaving only a disappearing contrail in our passing. Rogers covers many of these landscapes and concepts in the collection she called her “surprise pregnancy” during a CBC interview. In an online interview with The Malahat Review, she acknowledges the traditional territory upon which she wrote many of the poems (at the University of Northern B. C.), as well as the Ontario College of Art and Design. Once she came to the realization a collection was forming, “the rest flowed like a river.”

Victoria’s third Poet Laureate (2012-2014), Rogers is an eminent Mohawk/Tuscarora writer, orator, and artist who has resided on Coast Salish territory since the mid-nineties. She is truly an uncompromising multidisciplinary artist. This collection is experiential art. Rogers’ poetry is song: a chant, an oral story in written word. The songs take flight with her aural acoustics and active language—she both bends and blends form. Up in the ether, it was clear that Rogers’ poetry is part of the uni- (one) verse (song), as the recently departed Richard Wagamese reminded us in One Story, One Song. Rogers takes a bird’s-eye view of Canadian history, truth, and reconciliation—influenced by and well timed with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and the sesquicentennial anniversary of Canadian confederation. The collection contains no introduction or acknowledgements—the poems speak for themselves, soaring from the page with a sense of urgency, as in “Red Earth, White Lies”:

I am writing

new histories

absent of

white lies

from this

brown face

The collection takes off with the sensual “Body Song” and lands softly with “Bear Love.” Throughout the journey, Rogers explores the turbulent themes of identity, land, missing and murdered Indigenous women, communication, residential schools, resistance, and the beauty and mystery of reclaiming our shared history, change, growth, and evolution: “dancing on debris / knowing eight generations.” On the flight home, I gazed out the window and noticed the stitched scar of train tracks slashed across the land.

Although the collection has a hard edge—due in large part to the poet’s unwillingness to avert her eyes from the truth—there is also a lot of love. She honours many strong women from Pauline Johnson to Pocahontas. She highlights our shared humanity—“we are made of nature”—with a Ferguson shooting victim in “We Are All Michael Brown.” Her humanity speaks to our commonalities rather than our variance. The forms of the poems have a beauty on the page: expansive, artistic, playful, hard; which helps to reflect the lyricism of Rogers’ performance roots as well as suggest movement. “Antecedent” is like a slash across the page. The uniquely black and white poem “Lemme See Ya Dance” imbues movement with words. The first stanza of “Reckless” offers thoughtful pauses:

reckless ness

exists

in creation

random

and

spiritual esque

These poems are a marriage of life energy and experience and are “Calls To Action.” In “December,” Rogers intones: “there is / a time for intensity / and a place / to express it / there is / a time for calm / contented periods / but this isn’t it.”

By the time we touch back down on our home and Native land, my copy of Totem Poles and Railroads is fluttering with red flags marking wisdom, like “when entering troubled waters / make sure to wear turquoise” and words to remember: “celestial / connections.” Poems like “Where Are Your Guts” fill me with gratitude and courage: “we have hands to give thanks / our feet leave tracks.” The acknowledgement of the imperfection of the last 500 years helps us to see the humanity within one another, and that together we can do better—for our people and for our land. Reconciliation begins with recognition; these poems serve to both validate and educate us about the truth of our collective history as Canadians.

Read this book. Sing it, dance it, experience it. Bear witness, say a prayer, and pass on the knowledge. When you are sung awake by the ceremony, you become a participant in the process of healing.

—June Halliday