Reviews

Poetry Review by Paul Watkins

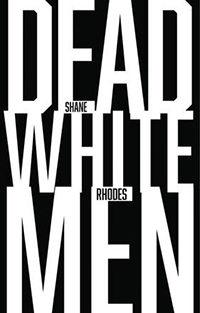

Shane Rhodes, Dead White Men (Toronto: Coach House, 2017). Paperbound, 112 pp. $18.95

Shane Rhodes’s stunning sixth collection of poetry, Dead White Men, repurposes settler texts with pioneering deftness (words cascade, fonts change, statues silhouette, language obliterates), using poetry to critically interrogate the Eurocentrism found in many foundational settler texts. While the names of many dead white men have faded in the annals of history, their mythopoeic justifications for colonization remain woven into the fabric of Euro-American society. Stories shape our beliefs and ethics, and so there’s good reason to go back to colonial origin stories, especially given the cultural amnesia around them. As Rhodes explains in the Notes section, “I was interested in looking to these past stories (especially those focused on North America and the South Pacific), not to add to the fictions of past white heroism but to better understand the problematic relationship between the stories, the mythologies they have become, and the lands and peoples they describe.”

Shane Rhodes’s stunning sixth collection of poetry, Dead White Men, repurposes settler texts with pioneering deftness (words cascade, fonts change, statues silhouette, language obliterates), using poetry to critically interrogate the Eurocentrism found in many foundational settler texts. While the names of many dead white men have faded in the annals of history, their mythopoeic justifications for colonization remain woven into the fabric of Euro-American society. Stories shape our beliefs and ethics, and so there’s good reason to go back to colonial origin stories, especially given the cultural amnesia around them. As Rhodes explains in the Notes section, “I was interested in looking to these past stories (especially those focused on North America and the South Pacific), not to add to the fictions of past white heroism but to better understand the problematic relationship between the stories, the mythologies they have become, and the lands and peoples they describe.”

The mythologies that comprise Dead White Men are extracted from journals, narratives, and historical texts from James Cook, Galileo Galilei, Jacques Cartier, and John Franklin to lesser known myth-makers like the chronicler George Best, who travelled with Martin Frobisher (Frobisher brought Inuit captives back to England), and Edward Dodding, who wrote a 1577 autopsy report entitled, “The Death of an Inuit Man in England.” Dead White Men repurposes the language of scientific discovery and colonialism found in these early European narratives of exploration in order to portray the violence and commercial exploitation enacted on Indigenous peoples and silenced landscapes. Dead White Men is comprised of two sections: the first focuses on settler texts in two parts titled “what is history / a whitish story” and “this country of science my soul,” and the other is a shorter section called “transit” that concerns, as Rhodes writes in this section’s note, “texts produced during the 1769 measurement of the transit of Venus...which was observed and recorded by over 170 observers at 77 posts around the world.” “Transit,” which is printed upside down and backwards (an inverted image of the first section), covers the South Pacific and the organized observation of Venus from Tahiti. Like the first section, “transit” concerns the impact that colonial narratives of scientific discovery have on the landscapes and people they depict.

Each section opens with sideways text (landscape orientation) to call our attention to the reputed authority these men hold and to “See their dead white faces in the crumpling map-scrolls of surf.” These dead white men were driven by a desire to claim their encountered landscapes: “land I have Named.” In “Naming it,” which excerpts James Cook’s journals to Tahiti and Australia, including a gratifying detail of stones being thrown at Cook, we are presented with a litany of names in a large enjambment of text that speaks to colonial erasure: “…I took formal possession of in the Name of His Majesty and named the / river Thames which occasioned my giving it the Name of Bream Bay in / honour of Point Pocock (after this they began to Pelt us with stones) so I / called it Cape Turnagain because here we returned to Doubtless Bay which / I am confident was never seen or Visited by any European before us….” Cook claims the East Coast of Australia for Britain without consideration or negotiation with local inhabitants and his acts of naming are tools of Empire building. Language aids colonization but, as Rhodes shows, poetic language, in this case flipping the script vis-à-vis erasure and cut-up techniques, can help to deconstruct and expose the fraught nature of settler narratives.

Even something as procedural as an autopsy report from 1577 demonstrates the colonizing potential of language. In “[He]: upon the death of Kalicho (1577),” Rhodes breaks apart language—in a style similar to Nisga’a poet Jordan Abel and Afrosporic Caribbean poet M. NourbeSe Philip—like the “two ribs broken” of Kalicho to show how Edward Dodding’s methodical language (brought into the poem through italicized quotation) treats an Inuit life as anthropometric specimen. While I read this poem, and others like it, I couldn’t help but recall the controversial Kenneth Goldsmith reading that used the Murdered Body of Mike Brown’s Medical Report as poetry. What feels different here, however, other than the removal in time and space, is that Rhodes works to expose systematic racism from a settler perspective while Goldsmith’s performance lacked self-reflexivity, ultimately re-dissecting Brown’s body under the guise of conceptualism. Conversely, Rhodes is conscious of the erasures happening in colonial documents, and his poems draw attention to these omissions, as various poems—like “Linguisticers,” which omits Inuit words—serve to underscore the settler violence enacted upon Indigenous people.

The same colonizing mentality of relentless settlement that writes over Indigenous history and presence also made the slave trade conceivable. In “Labrador”—a poem that “recombines the translated letters of Alberto Cantino and Pietro Pasqualigo” and “Trip Advisor reviews of the Antigo Mercado de Escravos in Lagos, Portugal … the likely endpoint for the kidnapped slaves”—details the voyage of two slave ships and speaks to how history continues to inform the present:

This is the contract history keeps.

Their bodies measured, sold, or thrown

down the Poço dos Negros (the Well ‘A slave market is NOTHING

to be proud of!’

of the Blacks) where, 500 years later,

skeletons are found while digging a parking lot.

Rhodes’s excavation of past skeletons (with an attentiveness to historical echoes in the present) makes for a challenging and playful read. By mashing and rubbing sources together—the poem “Gold” mixes historic texts about the search for gold with news articles about disasters and human rights violations at various mines—Rhodes emphasizes that poetry can help deconstruct colonial narratives by drawing attention to their very construction.

Idealistically, conceptual writing can go beyond concept and play an active role in decolonization. The images of the statues in the text are another reminder—especially given the recent protests of the Robert Edward Lee statue in Charlottesville and the Cornwallis statue in Halifax, among many others—that racist colonial monuments and narratives will topple through concerted efforts. For settlers willing to look at their own mythologies and dismantle them, Dead White Men offers a grammar of decolonization that can generatively be taken off the page and into the world.

—Paul Watkins