Reviews

Fiction Review by Shannon Webb-Campbell

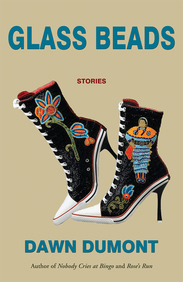

Dawn Dumont, Glass Beads (Saskatoon : Thistledown, 2017). Paperbound, 266 pp., $20.

Dawn Dumont’s talents as a writer and comedian are as interwoven as intricate beadwork. Her latest book, Glass Beads, is a short-story collection that explores the interconnected relationships between four First Nations people: Julie Papequash, Nathan (Taz) Mosquito, Nellie Gordon, and Everett Kaiswatim. Over twenty stories, and two decades—the ’90s and early 2000s, Glass Beads explores cultural and political shifts, family traumas, broken relationships, travel, and the global consequences of 9/11.

Dawn Dumont’s talents as a writer and comedian are as interwoven as intricate beadwork. Her latest book, Glass Beads, is a short-story collection that explores the interconnected relationships between four First Nations people: Julie Papequash, Nathan (Taz) Mosquito, Nellie Gordon, and Everett Kaiswatim. Over twenty stories, and two decades—the ’90s and early 2000s, Glass Beads explores cultural and political shifts, family traumas, broken relationships, travel, and the global consequences of 9/11.

As a Plains Cree comedian, actor, and writer based in Saskatchewan, Dumont has toured comedy clubs across Turtle Island, including the New York Comedy Club, New York’s Comic Strip and the Improv. Her comedic writing takes her back and forth between the stage and page, as a playwright, and for CBC Radio and the Edmonton Journal. Her colloquial diction and theatrical style complements her fiction, as her cast of lively characters are relatable, multi-dimensional, and tragically flawed.

All four characters have spent most of their lives off-reserve, yet deal with racism, colonialization, and intergenerational trauma from residential schools. Each character is in a state of transition. They are in relationships with one another, and embody their larger relations to the sky, land, waters, and ancestors. Nellie, Julie, and Everett grew up on Asinly Napew First Nation (formerly Stone Man’s), and Taz, who is from the North, and describes himself as “A real Indian. Not a fake-ass, mostly monias Indian, like these ones. Crow’s Nest First Nation,” in the short story, “Princess.”

In “New Year’s Eve,” Dumont uses a numbered list to describe Everett’s blackout drunks, including: “shooting his uncle’s rifle at an outhouse,” “eating dog food like it was cereal,” “puking all over his bed and waking up with his face in it,” “driving himself home,” and “passing out in strange places.” Whether Everett wakes up along the train tracks, half in and out of a pond, or in chicken coop, his behaviour escalates throughout the linked narratives of Glass Beads. Dumont successfully conveys the complexities of trauma, abuse, addiction, and how each character seems to mirror another.

When Julie goes on her first white-guy date in “Stranger Danger,” her hesitation and shyness are overthrown by her cast of roommates. She finds herself on the other side of racism years later in “Two Years Less a Day,” where she must serve jail time after having been wrongfully convicted of a crime. As a poet who has taught workshops to incarcerated Indigenous women, the scene when Mrs. Dixon, an elderly writing instructor, visits the jail felt familiar to me. Even though Mrs. Dixon falls asleep while the women read their poems of heartache and trauma, and express missing their children, Julie forgoes the poetry, and draws a cat. She quickly scribbles a note in an attempt to reach out to the outside world through Mrs. Dixon.

“She read them some poems by a woman named Emily Dickinson—‘she kept to herself most of her life,’ Mrs. Dixon explained and Julie envied that—what she wouldn’t give to have a room to herself for ten minutes.”

The lack of privacy, politics and conditions of prison push Julie passed the brink. Yet, it’s a moment in the collection where we see her start to pray, and attempt to connect to something larger. While Julie is most vulnerable, and continuously taken advantage of, in my opinion, she is the most relatable character. The tension in her relationship with Nellie, who envies Julie’s beauty, is an interesting insight into female friendship, and their ever-complex sisterhood.

While each character shifts, expands, and retracts, throughout Glass Beadsthere is a continuous sense of becoming, undoing, and redoing. Taz goes through an internal reckoning in “The Great Mystery.” “Part of the deal was that you had to feel something. Something bigger than yourself. A chief told him that one day. You may not start out that way, but you will get there. And the most important thing—and he said this in a warning voice—was to keep returning to that connection.”

The fact Dumont chose to write in short-story form instead of a novel is intriguing. Each of these stories can stand alone, as they embody the particular mechanics and structures of short fiction, yet Glass Beads also feels like a fully realized, deeply narrative longer form. Part of the gifts of a short story is how some threads can be picked up, and others dropped. Much like beadwork, each strand or story stands on its own, but can only be fully formed in relation to others.

In “The Curtain,” the final story in the collection, Dumont writes, “Better to smoke and laugh than hope for anything else. Better to enjoy that brief time they got together.” Storytelling is a sacred responsibity. Dumont’s Glass Beads is carefully crafted, and inhabits both past, present, and futures. As stories have the ability to shift perspective, transform realities, and, potentially, repair, Dumont’s collection is both a teaching tool, and a finding place. Her role as storyteller and comedian come together in an authentic portrayal of the realities facing Indigenous people.

—Shannon Webb-Campbell