Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Christin Geall

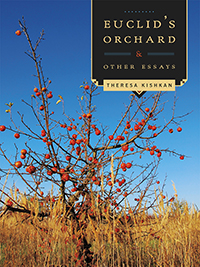

Theresa Kishkan, Euclid's Orchard & Other Essays (Salt Spring Island: Mother Tongue, 2017). Paperbound, 168 pp., $22.95.

In Theresa Kishkan’s new book of essays, the archaeology of simple lives is made wonderfully complex by the excavations of the writer. This is a literary book first and foremost, esoteric at times and oddly plebian at others. The writing is clear, calm and precise, the tone measured. The stories within the essays—researching lost relatives, exploring gardens and landscapes—never flap or snap. Methodical and mellow, these are meditative essays, controlled, inquisitive and, at times, beautiful. The writing is at its most lyrical in the sections on nature. Kishkan writes of the Albertan landscape of her ancestors with a keen eye, ecological understanding, and poetic style: “Turn, turn, bend the song to the roadside plants, the hosts, long syllables short ones, free verse composed of craneflies, dragonflies, bluebottles, broad-bodied leaf beetles, greasewood and cocklebur, the miraculous monarchs hovering.”

In Theresa Kishkan’s new book of essays, the archaeology of simple lives is made wonderfully complex by the excavations of the writer. This is a literary book first and foremost, esoteric at times and oddly plebian at others. The writing is clear, calm and precise, the tone measured. The stories within the essays—researching lost relatives, exploring gardens and landscapes—never flap or snap. Methodical and mellow, these are meditative essays, controlled, inquisitive and, at times, beautiful. The writing is at its most lyrical in the sections on nature. Kishkan writes of the Albertan landscape of her ancestors with a keen eye, ecological understanding, and poetic style: “Turn, turn, bend the song to the roadside plants, the hosts, long syllables short ones, free verse composed of craneflies, dragonflies, bluebottles, broad-bodied leaf beetles, greasewood and cocklebur, the miraculous monarchs hovering.”

Kishkan is a writer’s writer and it’s her voice that holds the layered narratives in “Euclid’s Orchard” —the piece from which the collection takes its name – together. The subject of the essay is the author’s desire to understand the mathematical language of her son and, through her exploration, we discover how the family orchard was established and abandoned, how the author quilts and why, and how she understands the world through language. Kishkan holds the reader’s attention across this range of subjects by revealing the machinations of her own mind.

However, “family is both the source and inspiration for the essays collected in Euclid’s Orchard,” and that is regrettable. In the opening essay on her father, “Herakleitos and Yalakom,”—the most poignant essay in the book—Kishkan writes: “At this point in my life I’m trying to make sense of the knot-work of relationships—yours to me, mine to you and my mother, the loops my brothers make in and amongst you, me, how we are tied to each other, places, hitched and slipped and reefed.” This call-to-memory’s-arms appears early in the book and establishes trust in the narrator, setting us up for her interrogations of the past. But questions of intent nagged at me as I read on. Why are you telling me this (in this form)? Is it an idea of legacy that drove you on or an essayist’s quest for identity? And if the latter, why so few juicy details of your own life, why so little drama?

This is the challenge of an essay collection that leans towards family and biography: the author’s pulse is the one we feel most. Stories of ancestors, whether couched in the author’s discovery or not, can only be as interesting as those people were, and let’s face it, many of us are not.It requires tremendous skill to animate lives, let alone make sense of them, and Kishkan gives it her best in this book, breaking many of the essays into segments, weaving in ruminations to liven things up. Yet, by end of the book, I felt that nothing was truly made sense of, the knot-work made more complex, having been intellectually tackled as opposed to emotionally teased apart. I felt more confounded, the essays leading me from the Maritimes, to the Fraser Valley, to the Sechelt Peninsula and the aforementioned Alberta, all the while peopled with interrogations about strangers whose stories meant little to me.

In the essay ”Poignant Mountain,” there’s a nod in the notes section that the essay is a “memory map,” and a quote from Herman Melville used as kind of disclaimer for how the author’s memory may differ from the actual places described: “It is not down in any map; true places never are.” A clever quote and approach, but memory’s subjectivity may have been a more provocative topic for an intellectual essayist than a ramble about town.

Perhaps my struggles with the book could be a result of the fact that I’d just endured a slew of holiday dinner parties when I cracked it open. Unfortunately, for the author, I’d decided people could be conveniently divided along the lines of those who like to tell stories and those who prefer to converse. Like any easy binary, this little model of mine was quickly applied to other pursuits: How do we speak to readers as nonfiction writers? Do we entertain with story? Or enquire and propose? And is it best to do both? Kishkan does the latter and in the end this book surprised me, as questions of place resonated long after I’d finished it. Can we really know where we are from? I doubt it, and thankfully so does Kishkan in this small but rigorous book.

—Christin Geall