Reviews

Fiction Review by Colin Loughran

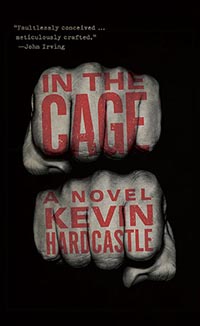

Kevin Hardcastle, In the Cage (Windsor: Biblioasis, 2017). Paperbound, 310 pp., $19.95.

In the Cage owes much of its power to the sense of entrapment it creates. Throughout, the decisions made by the novel’s protagonist, Daniel, are framed as the inevitable consequence of the metaphorical cage in which he lives, and signifiers of financial strife—a second mortgage, a denied loan application, an unexpected layoff—are punctuated by the trauma of more literal forms of violence. As a naturalist meditation on the economics of desperation faced by Northern Ontario’s rural poor, Kevin Hardcastle’s novel repeatedly demonstrates how tight margins and bad luck can press otherwise good people into a corner.

In the Cage owes much of its power to the sense of entrapment it creates. Throughout, the decisions made by the novel’s protagonist, Daniel, are framed as the inevitable consequence of the metaphorical cage in which he lives, and signifiers of financial strife—a second mortgage, a denied loan application, an unexpected layoff—are punctuated by the trauma of more literal forms of violence. As a naturalist meditation on the economics of desperation faced by Northern Ontario’s rural poor, Kevin Hardcastle’s novel repeatedly demonstrates how tight margins and bad luck can press otherwise good people into a corner.

The broad strokes of this story will be familiar to most readers: a once-promising mixed-martial arts fighter, Daniel is drawn back into the ring in an attempt to make good for his struggling family. Hardcastle’s accounts of these fights do much to engage the reader, and we see Daniel at his most empowered in these scenes, but it’s also clear that a long-term comeback is never an option. Ultimately, his entanglement with organized crime—where his ability to hurt people is equally valuable—brings about the ruin of Daniel and those around him. “Nobody ever gave him a decent job in his life,” his wife, Sarah, tells the local crime boss in a plea to be left alone. “Can you believe it? A good man like that.”

Does a narrative framed around inevitability necessarily owe it to the reader to be more surprising or original? Perhaps not, yet comparisons to Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men, another backcountry thriller that flies a similar flag, seem inevitable. Still, McCarthy’s novel manages to defy the expectations of the genre instead of reinforcing them. Hardcastle’s novel even has its own version of No Country’s remarkable villain, Anton Chigurh. Like the terrifying Chigurh, Tarbell seems chillingly remote from any codes of honour, and he commits senseless atrocities far beyond the requirements of criminal enterprise. When he murders two strangers in a parking lot, he takes the time to watch “the last plume of fog depart the workman’s lips.” However, unlike McCarthy’s monster, whose nihilistic allegiance to random death makes him a fascinating narrative cipher, Tarbell ends up more like a prop than a provocation. Like the technicality that costs Daniel a crucial win in the ring, he represents just another bit of hard luck and, as such, he’s the least convincing character in the novel.

The author also often writes in a kind of hardscrabble polysyndeton—or “spare, muscular prose,” according to the publisher—that seems de rigueur for young male writers growing up in the shadow of McCarthy. “He put them down and threw another light jab and then a hard jab and felt the heft of the bag under his raw knuckles and then he threw a one-two and stung the bag with a straight right and sent it spiralling counter-clockwise.” If you think of each conjunction as a body blow, then there’s something to enjoy here, but my attention occasionally wavered, and I suspect this prose will likely repel some readers. That is a shame, though, because Hardcastle is a talented writer, and when his language unclenches it shines. The moments between the potboiler carnage evince a rough-hewn texture that captures both the beauty and the sadness of the characters’ working-class existence. Take, for example, Hardcastle’s lyrical sketch of Daniel’s town on Georgian Bay, which explores the intersections of time, space, and memory through crystal-clear detail: “Houses rebuilt and others gone to rot. New roads and subdivisions at the high side of town. River valley where the body of a local girl had been found. A debris-strewn promontory near the docks where a grain elevator used to be. Malls and superstores on the westerly edge of town atop forest where he’d rode and ran. Entire universes that he’d invented as a boy paved over, places now for plazas to squat and shit.” Throughout the novel’s quieter chapters, the experiences of its characters are revelatory of other more insidious forms of violence, and of how progress for some might represent loss for others.

Tarbell aside, many of Hardcastle’s minor characters are exceptionally rendered, and this goes a long way in reinforcing the novel’s sense of place. The author is particularly gifted at capturing paralinguistic gesture, showing how small actions communicate interiority: “Sarah took his hand in hers and put it to her cheek. She let go and sat up straight and poured more wine. Took a swig from the glass.” Be it a caress across the cheek or a blow to the head, Hardcastle seems to emphasize touch and sensation above the other senses in order to show how crushing poverty reduces people like Daniel and Sarah to mere physical beings.

In the Cage is a strong first novel that wrestles with its influences. The narrative’s imperative—its ceaseless thrust toward violence—works both for and against it, but Hardcastle mostly steers into the skid, finding novelty not in plot but in the remarkable details of place and character. Certainly, hyper-masculine violence need not be the lynchpin of stories of the working class, and it’s not necessarily a virtue for prose to be “taut” and full of “rigour”—whatever that means—but Hardcastle’s ability to find truth in minor details frequently overcomes these inherited faults. This is a highly crafted piece of crime fiction, and when you strip away the genre’s trappings, you find something truly special.

—Colin Loughran