Reviews

Poetry Review by Chris Jennings

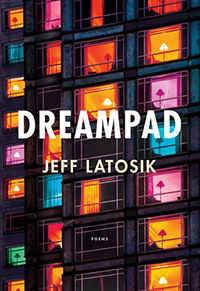

Jeff Latosik, Dreampad (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2018). Paperbound, 118 pp., $19.95.

Title poems bookend Jeff Latosik’s third collection, but only the second one reveals that a “dreampad” is a “magic pillow.” Apparently, it uses bone conduction to transmit calming music to the inner ear via the bones of the skull so that only the person whose head is on the pillow can hear it. I can see how something like this would be attractive to a poet’s imagination. It runs on a technology that seems like magic; its purpose is to help you dissociate from your immediate surroundings (even the person next to you in bed), and it achieves its purpose by simulating the effect of experiences that, presumably, make one feel connected to the world (listening to music, listening to calming nature sounds). Of course, the word “dream” also sits within it, with all of the connotations of a distinction between reality and dreams, or of dreams as subconscious desires and anxieties. And these are the main preoccupations of Dreampad: estrangement (including estrangement from a reality that sometimes feels contingent), lack and a yearning for what is missing, and the paradoxes of our brilliant attempts to address that lack with, among other things, technologies that also increase our estrangement. Both the themes and the unpacking of the way they come together in objects or quotidian experiences then spark questions about the nature of our experiences and relationships.

Title poems bookend Jeff Latosik’s third collection, but only the second one reveals that a “dreampad” is a “magic pillow.” Apparently, it uses bone conduction to transmit calming music to the inner ear via the bones of the skull so that only the person whose head is on the pillow can hear it. I can see how something like this would be attractive to a poet’s imagination. It runs on a technology that seems like magic; its purpose is to help you dissociate from your immediate surroundings (even the person next to you in bed), and it achieves its purpose by simulating the effect of experiences that, presumably, make one feel connected to the world (listening to music, listening to calming nature sounds). Of course, the word “dream” also sits within it, with all of the connotations of a distinction between reality and dreams, or of dreams as subconscious desires and anxieties. And these are the main preoccupations of Dreampad: estrangement (including estrangement from a reality that sometimes feels contingent), lack and a yearning for what is missing, and the paradoxes of our brilliant attempts to address that lack with, among other things, technologies that also increase our estrangement. Both the themes and the unpacking of the way they come together in objects or quotidian experiences then spark questions about the nature of our experiences and relationships.

This is a mature book (and a long one) marked by its unity both of voice and of persona. The writing is consistently strong, and I mean that pedantically. Latosik constructs poems that would have made every stereotypically gruff newspaper editor happy with their economy. The voice seems colloquial, but he punctuates familiarity with diction that reflects the technical language of his subjects. Similarly, while the voice is generally discursive, bursts of rhyme or elevated sound disrupt the illusion of conversation, like the unexpected end-rhyme in “The Home Checklist”:

No powerline static

Minimal landscaping of the greenery required.

For that matter, no attic.

Stylistically, it’s an interesting parallel to the book’s themes. The language is transparent until it’s not; a peripatetic, associative series of thoughts is allowed to wander until it finds its mark, as in these lines from “The Natural”: “When we think of the place we’re meant to be / doesn’t it all seem to unfold so effortlessly?”

The first “Dreampad” in the book captures how well Latosik orchestrates the interplay of estrangement and desire, technology and dreams. It starts directly into an extended metaphor that figures sleep-addled memory as music produced with the help of technology: “[T]hen the grid / populates as memory, which has reverb // and you best believe it has attack.” The poem moves by this device to its emotional core and a particular memory, a moment when the speaker’s mother and stepfather were “heading in the same direction for the last time.” The metaphor gives the speaker a vehicle to imagine changing the reality he remembers: “I make all that isn’t / come to in a half-life of being dreamed and as I do the days // patch through in a way that’s hard to damp and fade. / Strange, though, my remixing’s not my stepfather getting clean, // or my mother finally getting to live beside the Atlantic.” Latosik regulates the emotional register with the technical language of someone familiar with a sound board, but he also bolsters it with the musicality of short, assonant syllables, “days,” “way,” “fade,” and “Strange,” that mimic static on the track the speaker tries to create, and the consonance in “dreamed,” “do,” “days,” “damp,” and “fade.” But as the poem moves to its end, the figurative density of the language changes when dealing with the awareness of loss: “I play better than I once did / the older that I do. I missed something that made my life.” That last, simple statement is a long way from the abstractions with which the poem begins, and you could be forgiven for forgetting any mention of a dreampad, but the sense of estrangement from one’s own life couldn’t be any more raw.

Latosik applies a similar type of perception to floodlights, spacetime, characters in Steven Segal movies, and the platypus. Sometimes, the emphasis is on technology as a way to address desire: “Car makers wanted to win each of us / by leaving nobody’s wants unmet”; “you’re met, / as ever, by the range of choices your qualm half fits, / a cache of wants crushed on a touchpad of options.” But more often, the world Dreampad creates is a malleable reality: “I used to have this thought that one day / I’d wake up in a different life, and all here was / was an atomic flash. Some nightmare of a self”; “[w]henever I’ve heard reality’s just so there, / […] / I lean back in my chair and a breeze enhances what I’m feeling”; “It wouldn’t be wrong // to say that lostness is always there on the lip of everything, / like lichen or a bomb.” The final “Dreampad” draws much of this together—“[m]y dreampad is a buffering / of waking-ness, of wanting, and so it takes the suffering / I might be and stretches it again, again, into a synth note”—but it would take multiple readings to draw out the subtleties that run through this well-constructed book.

—Chris Jennings