Reviews

Fiction Review by Justin Pfefferle

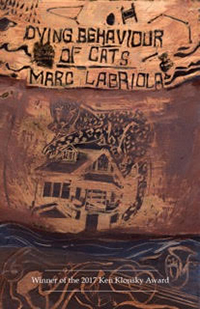

Marc Labriola, Dying Behaviour of Cats (Toronto: Quattro, 2018). Paperbound, 124 pp., $20.

When cats anticipate dying, the narrator of Marc Labriola’s novella tells us, they prefer solitude. Where they might once have sought companionship, the affections of their owners and strangers alike, their sense of impending mortality—whether conscious or instinctual—prompts them to hide. Do cats elect to die furtively as an act of dignity, or as an effort, in their final days, hours, minutes, not to be a bother? Or does their preference for dying alone reflect a special kind of existential wisdom that accompanies a confrontation with death: the wisdom of Sartre, who tells us in his play No Exit that Hell is other people?

When cats anticipate dying, the narrator of Marc Labriola’s novella tells us, they prefer solitude. Where they might once have sought companionship, the affections of their owners and strangers alike, their sense of impending mortality—whether conscious or instinctual—prompts them to hide. Do cats elect to die furtively as an act of dignity, or as an effort, in their final days, hours, minutes, not to be a bother? Or does their preference for dying alone reflect a special kind of existential wisdom that accompanies a confrontation with death: the wisdom of Sartre, who tells us in his play No Exit that Hell is other people?

Lest the reader fail to pick up on the connection between Gato Barbieri, the neighbourhood cat who gives himself license to die only after Theo, Labriola’s protagonist, leaves him alone, and Theo himself—an agoraphobe who, we are told in the second chapter, “hadn’t left the house in seven years”—the narrator drives the point home. “Theo too was perfecting his solitude. Living out, day to day, the dying behaviour of cats.” Like all of us, Theo is dying: not of any ticking-time-bomb disease, but by virtue of living during what eco-philosophers have come to call the Anthropocene, the current geological age, a period characterized by human activity having an immediate, dominant effect on the environment. Confined to the home of his dead, then dying, father (the narrative hopscotches back and forth in time), Theo has a front-row seat to what might be the Final Catastrophe. Extreme weather events, including a hurricane named, coincidentally, after Theo’s estranged wife Catalina, food shortages, and riots in every major city around the globe, provide a backdrop to his psychological tumult, which constitutes the main point of narrative focus. And as the planet tells its human inhabitants that it, too, would like to die alone—for what proves Sartre’s point better, more finally, than global climate change?—Theo thinks, mostly, about cocks.

Cocks—human and insect, flaccid and hard, amputated, spray-painted, illicit, ornamental—abound in Theo’s life and imagination. And so, for the space of some one-hundred and twenty-three pages, do they abound in those of the reader. Early on, Theo’s father undergoes a penectomy after his cock turns blue, a symptom of what he calls “dick cancer.” Nothing, one guesses, instigates castration anxiety like one’s father having his cock chopped off; predictably, Theo later dreams of being cut up in pieces, “[h]is balls rolling down the stairs.” When he realizes that his agoraphobic unwillingness to leave his father’s home (the hurricane building outside and the leopard perched atop his roof notwithstanding) has turned him into a news-item curiosity, he considers “drooping his cock out the window”—an act of exposure that, had he gone through with it, would doubtless have made him the hero of teenage boys everywhere. Showing his cock to the world would also have made him a double of the man Theo places at the centre of the “incident with the cock”: about five years earlier, he recalls, he watched and “did nothing” as a man exposed himself to two teenage girls, who screamed and ran down the street, fearful, no doubt, of what the flasher aimed to do with the cock in his hand.

There is, of course, a commentary being made here: Theo’s phallophilic response to the end of the world, to say nothing of his failure to intervene with the flasher—maybe even to “cut his dick off”—symbolizes humanity’s, ahem, impotent response to the problem of global warming. We are all, in effect, holding our dicks as the world becomes more uninhabitable day after day. In art as in life, however, cocks have limited staying power: as a narrative trope, the cock rather wears out its welcome in the novella, where it recurs with such frequency—indeed, the word “cock” appears on virtually every page—as to become, well, pretty tired. The problems facing the planet today require a grown-up response; is there anything less grown-up than a sustained dick joke? Most boys outgrow—or at least learn to sublimate—the fascination with their cocks that begins that fateful day when they discover their genitals in the bathtub, letting go once the Ego develops enough to mediate the Id’s instinctual drives. One wishes, after a while, that Dying Behaviour of Cats would grow up—or at least invite an adult in the room to mitigate its most childish impulses.

The centrality of cocks means the novella has almost no space for women: by the time the narrative begins, Theo has been doubly abandoned, first by his mother, then by Catalina. Theo’s ruminations on loss, especially those in relation to women who are no longer in his life, yield the most moving moments in the book and provoke the most refined writing and ideas. Labriola describes his character’s brooding over the loss of Catalina thus: “His own body had phantom pains where she used to belong. Theo was so consumed by missing her that he became afraid of his own sadness. Afraid that her body was forgetting his.” He extends the image of interconnected bodies later, when he depicts Theo imagining a reunion with his long-lost mother: “He imagined how they would meet. They would hug. She would be thin. Pretty. He would feel her again for the first time since he was born. When he knew her from the inside. And his body would remember hers like a childhood sickness, like chicken pox at three years, now dormant in his body, preventing itself from ever returning in the exact way as it hurt him the first time.” This last sentence notably deviates from the dominant style of the novella, in which Labriola confronts the reader with the kinds of clipped, active, declarative sentences that recall, even to the level of parody, the macho, virile prose of Hemingway. It can be a bit much: the writing is at its best in the rare instances when subordinate and parenthetical clauses disrupt the relentless forward surge of the prose.

The primary virtue of Dying Behaviour of Cats is that it risks being strange. It invites readers into an experience of agoraphobia by locking us into the mind of its protagonist, whose perception of the world beyond himself—is the leopard on the roof real or a projection?—we are at once meant to question and unable to see beyond. Its preoccupation with cocks becomes confining in a way that the novella struggles to manage. Still, given the urgency of our current predicament, one can perhaps understand, if not ultimately endorse, the impulse to retreat from the world and die alone, cock in hand.

—Justin Pfefferle