Reviews

Misc. Reviews by Jessica Johns

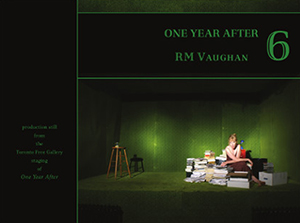

RM Vaughan, One Year After (Victoria: Frog Hollow, 2018). Paperbound, 48 pp., $15.

Rae Congdon, GAYBCs: A Queer Alphabet (Vancouver: Greystone, 2018). Hardbound, 60 pp., $21.95.

RM Vaughan’s One Year After is a tightly written, scripted performance piece for one actor. The author’s notes state that the work is not gender scripted, though Vaughan’s iteration takes a female lesbian character, Elaine. Delivered in a poetic monologue, the actor weaves memory and self-reflection to tell a story of her fraught relationships with her parents, their deaths, and her own struggles with depression and suicidal thoughts.

RM Vaughan’s One Year After is a tightly written, scripted performance piece for one actor. The author’s notes state that the work is not gender scripted, though Vaughan’s iteration takes a female lesbian character, Elaine. Delivered in a poetic monologue, the actor weaves memory and self-reflection to tell a story of her fraught relationships with her parents, their deaths, and her own struggles with depression and suicidal thoughts.

Elaine’s story begins slowly; she talks candidly about her own anxieties and how mental health concerns from queer folks are often disregarded by others (namely, heteronormative folks) and categorized under damaging generalizations and stereotypes often given to queer people (in the case of Elaine, it’s the “bitter lesbian”). She relives her experiences of micro-aggressions from her family, such as getting the job of cleaning out her mother’s house after her death because “apparently, heterosexuals are incapable of putting old towels and chipped tea cups in boxes.” The emotional weight—represented here by physical labour—put upon queer folks by heteronormative people can often cause further grief.

The story continues to quicken as Elaine describes additional aggressions, perpetuated by people both inside and outside the queer community. The actor is told by “some smart bitch” that “after 40, lesbians either go biker or blousy,” which leads Elaine to try both before finding that neither fit, and coming to the bitter conclusion that it’s “funny how you forget what your body can’t live up to, until you’re in front of the mirror, startled by ugliness.” The compounded effect of gaslighting queer experiences and forcing binaries on queer identities results in individual uncertainty, and shines a bitter and truthful light on how these aggressions can lead to personal displacement. In the case of Vaughan’s script, it leads to something even darker.

I question whether some parts of this script, though it claims to not be gender-scripted, would work if the character were male or non-binary. For example, when Elaine says “The message here, one I’ve heard all my life, was, You have to shut up and wait your turn. A woman has to wait her turn.” This is a gendered violence to which there is simply no male equivalent. While a production adapting this script should be able to change these moments to speak to different gender violences or harmful generalizations, it goes to show that writing something that isn’t intended to be gender-scripted isn’t as simple as changing gender pronouns and identifiers.

Vaughan offers some scathing and blunt truths about heteronormative folks, such as “when you’re past 40 and you have a few unkind observations about the world, if you’re a lesbian people say you are bitter. If you’re straight, they admire your clarity. Oh, you’re the fucking Buddha. And you get a weekly newspaper column.” Moments like this, combined with the claustrophobic setting of pairing a small, cluttered room with a distinctly anxious actor, have an astounding effect: it confronts the optics of the heteronormative gaze and points it inward. It makes folks uncomfortable in the reality of queer gaslighting, and the truths of heteronormative privilege. It’s a quiet discomfort, and a necessary one to endure for those benefitting from this privilege.

Rae Congdon’s GAYBCs: A Queer Alphabet is a fun, playful book that gives a queer spin on the alphabet; instead of learning letter-to-word association like “a is for apple” and “b is for banana,” you’re learning terms and definitions associated with queer culture, such as “femme” and “drag.” Additionally, a portion of the proceeds made from book sales are donated to Rainbow Railroad, an organization that helps LGBTQ people around the world find a safe haven from persecution.

Rae Congdon’s GAYBCs: A Queer Alphabet is a fun, playful book that gives a queer spin on the alphabet; instead of learning letter-to-word association like “a is for apple” and “b is for banana,” you’re learning terms and definitions associated with queer culture, such as “femme” and “drag.” Additionally, a portion of the proceeds made from book sales are donated to Rainbow Railroad, an organization that helps LGBTQ people around the world find a safe haven from persecution.

Though this book is intended for all ages, from children, to teenagers, to grandparents, the language and definitions remain accessible and the fun and colourful artwork with which each letter/definition is paired adds to the aesthetic enjoyment (a personal favourite of mine is “k is for kink” paired with pierced red lips). Beyond the definitions associated with queer culture are also hinted definitions for positive heteronormative-queer alliance. For example, under “Judgement-Free” the definition is “No time for negative! Live and let live” and under “Prejudice” is “Preconceived opinion that isn’t based on actual reason or experience.” This suggests to the reader methods of engaging with and thinking about queer individuals that go beyond boxes of definitions and instead relate to active interpersonal relationships.

As with anything that is intended to act as a starting-off point, sometimes I was left wanting further explanation or nuance. For example, under N is “Non-binary,” with the definition “Any gender identity that isn’t exclusively man or woman, like genderfluid, 2-spirit, and agender.” A Two Spirit identity for Indigenous communities is a sacred one, is differing and specific to each nation and community, and has far greater implications than the synonymous relation to non-binary is able to give. In fact, there are many Two Spirit folks who wouldn’t identify as non-binary, as the language behind the idea of binaries can be ideologically problematic to some. While a deep explanation of all of the terms is beyond the scope and intention of the book, it’s important to recognize that for some folks, clear-cut grouping, strict translations, and stripped-down definitions aren’t always possible.

This short book is intended as more of a coffee-table read than as reference material, but could act as a great access point for friends and family members of the LGBTQ community, to start conversations and engage with queer culture in a more meaningful way.

—Jessica Johns