Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Ricky Varghese

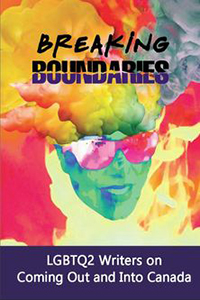

Lori Shwydky, editor, Breaking Boundaries: LGBTQ₂ Writers on Coming Out and Into Canada (Nanoose Bay: Rebel Mountain, 2017). Paperbound, 143 pp., $13.95.

The age-old adage that the personal is political is put to test in Breaking Boundaries. This intriguing amalgam of short stories, personal anecdotes, poetry, and visual art offers a platform for diverse voices to share their specific and particular experiences about what it means to come out—and how this act has personal, political, social, and societal implications. The idea of such a discursive anthology sounds promising; however, the end result might leave some readers wanting.

The age-old adage that the personal is political is put to test in Breaking Boundaries. This intriguing amalgam of short stories, personal anecdotes, poetry, and visual art offers a platform for diverse voices to share their specific and particular experiences about what it means to come out—and how this act has personal, political, social, and societal implications. The idea of such a discursive anthology sounds promising; however, the end result might leave some readers wanting.

What does it mean to come out? To be sure, the collection does not offer an easy-to-name answer to the question; rather, its various contributors attempt to tell (be it in the manner of fiction, poetry, or creative nonfiction) what coming out means to them, especially within the specific socio-cultural and political context of Canada, often hailed as a safe haven and refuge for LGBTQ2 people. The text leaves the question open-ended, allowing for possible and even extensive debate and discussion on the subjective nuances and particularities of the coming-out process, and this is perhaps the collection’s most potent quality. That being said, while all the contributions here orbit around this thematic centre that is the experience of coming out, there appears to be very little in common that serves to make the text a cohesive whole. At its core, this could be due to a lack of close and careful curation. There seems also, in tandem with the concern regarding curation, to be some confusion regarding who the presumed or imagined readership for the collection might be.

There are mature and rigorously insightful pieces here, like Gail Marlene Schwartz’s “Threads,” incredible non-linear and poignant vignettes that move back and forth across time and place to painstakingly detail the narrator’s anxieties in relation to her sexuality, to coming out to her own family, to meeting her partner, and to their decision to start a family. The result is a stunningly moving coming-of-age piece. Anne Hofland’s “Are You a Lesbian?” is yet another reflexive essay showcasing a profound maturity in thinking about the very craft of writing and how it might be honed to writing about oneself. Here we find a writer, having taken up writing late in life, reflecting about her years in the proverbial closet in the seventies and eighties. She examines what it means to look back across the decades, and to have witnessed the shifts, the ebbs and flows, that have occurred in the scene of queer history and politics in Canada.

Peppered across the text, however, amidst such intuitive pieces as those by Schwartz and Hofland, are others that lack a similar sense of reflexivity and maturity. There are pieces here that feel derivative, not particularly original or new in regard to thinking about queerness, or coming out, or what insights they might offer the reader. In reading, I was taken back to the very early days of my own formation as a young queer man, in the mid-nineties, attending slam poetry and open-mic nights at Crews and Tangos in Toronto, listening to readings of prose and poems about the suffocating claustrophobia of the closet, about the pain of rejection from one’s own family or friend circles, about the incommensurable, intangible, and even the fungible, nature of queer bodies, or about the many forms of violence that those very same queer bodies might be subjected to. It is not that such narratives are unimportant or inconsequential, or that they shouldn’t be told. It is that such pieces seem nostalgic and uncanny, especially when penned by those seemingly far younger than the likes of Schwartz or Hofland. Further to this, some of the authors have more than just one contribution in the text, which might make a reader wonder if a wide-enough net was cast to solicit works and what that wider net might have yielded.

As the subtitle to the text—LGBTQ₂ Writers on Coming Out and Into Canada—suggests, the collection attempts to offer a treatment not only of the experience of coming out, but also of the experience of coming to Canada as LGBTQ2 migrants and refugee claimants. The resulting narratives—say, in the case of “Out of Africa,” describing the migration story of a couple, MiraRita and Kani, or of another couple, Rainer and Eka, in ”Escaping Indonesia”—though intensely personal and profoundly subjective, position Canada in a somewhat uncritical light in relation to the elsewhere beyond its borders. The elsewhere is construed as a place to leave—to get out of, to escape from—for possibly very legitimate reasons, such as fleeing from persecutory violence. I wondered, however, if these pieces also, in their own way, reinforce the foreignness and otherness of these other geopolitical coordinates.

Not to mention that migrating to Canada or making a claim for refugee status is an exceptionally long process fraught with its own myriad challenges. Although there are other pieces here that attempt to unpack the challenges of being queer and visibly racialized or Indigenous in Canada, they generally lack depth, end up reading more like personal confessionals, and do not work to critically offset the otherwise celebratory tone by which Canada is rendered.

All in all, when taken as a whole, the resulting text appears to be a hodgepodge of genres, of generational disparities with regard to an understanding of queerness and coming out (which in itself might not actually be a “bad” thing), and of vastly differing levels of writing skills. Once again, I wonder who the imagined reader was meant to be.

—Ricky Varghese