Reviews

Poetry Review by Michael Kenyon

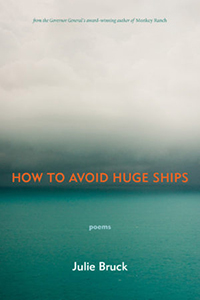

Julie Bruck, How to Avoid Huge Ships (London: Brick, 2018). Paperbound, 84 pp., $20.

Julie Bruck was born in Montreal and lived there for many years before winding up in San Francisco a couple of decades ago in the Inner Sunset district. Her resume is long on teaching and workshop facilitation and she has published four poetry collections, all with Brick Books. The length of time between books (The Woman Downstairs, 1993; The End of Travel, 1999; Monkey Ranch, 2012; and Ships, 2018) tells me that she is concerned deeply with poetry and with cultivating and nurturing its spark in others. Even a quick read of her work shows her to be a careful poet, one who spends much time mulling and editing each piece through several drafts. She is scrupulous about tone, meaning (obvious and subtle), and clarity of voice and vision.

Julie Bruck was born in Montreal and lived there for many years before winding up in San Francisco a couple of decades ago in the Inner Sunset district. Her resume is long on teaching and workshop facilitation and she has published four poetry collections, all with Brick Books. The length of time between books (The Woman Downstairs, 1993; The End of Travel, 1999; Monkey Ranch, 2012; and Ships, 2018) tells me that she is concerned deeply with poetry and with cultivating and nurturing its spark in others. Even a quick read of her work shows her to be a careful poet, one who spends much time mulling and editing each piece through several drafts. She is scrupulous about tone, meaning (obvious and subtle), and clarity of voice and vision.

“To the Bridge,” the opening poem of the first section, “Maps,” is set in “what remains of an afternoon,” which refers not only to the time of day, but also to the time of life we boomers find ourselves in. Seventeen lines of this twenty-six-line, single-stanza poem describe a simple meeting on “a quiet park trail” between a teenaged boy and the narrator, a woman, a mother “trained / to give him anything he wants.” The narrator gives the boy/man directions, receives thanks, and they part. The remaining nine lines are soliloquy and conclusion. A brief exchange, not without tension, happens, is commented on, and the collection gets rolling. Here is our map: a human connection, then a modest dialectic. The final line, “I may have drawn this one a map,” points directly toward the possibility of a suicide: “someone’s son walks west, / gaining on the Golden Gate Bridge / where so many beautiful boys fly.”

The book’s overall structure is not elaborate: six sections, a gentle lift and fall to each, with a warm invitation to a variety of readers to try some of the depths this fine poet is navigating. From “Maps” to “Small Largesse,” the final section, curtains open again and again on parents born in the 1920s. Julie Bruck, one of the “pot-fuelled, latchkey teens” (from “Dominion Protectiontm”) born in the 1950s, speaks of childhood, but more often of much later encounters with her parents and their generation in their frail last years and months. Of a mother “In January”:

Now she is calm, the days passing

like ghost ships through the long

winter, as words grow harder to

extricate from the mind’s dark horde ….

To spend time with parents in their nineties is to witness final acts, final words. Bruck records her complicated feelings for these familiar, becoming-strange folk, and develops on the page, as we read, strategies for catching and releasing the experience of their going. Perhaps this tactic will allay the writer’s personal fear: that real darkness will seal off the cave entrance through which we must pass to find our tools.

The poems in “Killer Shrimp” (the second section) take a step back; darkly humorous poems attempt a wry, sometimes ironic touch to shift the reader into a more global perspective. If we get the message, it is usually news we don’t really want; as we are asked to look squarely at individual aging humans and participate in the quest for clarity that underlies nearly all the poems, we behold a diffident, if not fucked-up, world.

In “Two Fish,” a second-person, let’s-say poem, the two goldfish you buy and nurture end up forgotten, on top of “a high shelf,” and when found still alive, barely, ages later, have developed at-odds compensatory characteristics: “…One sinks to the bottom, / distorted as a funhouse mirror…,” the other “swims off briskly.” This is what we do, the poem suggests, to our children, our loved ones. There’s no solution, only shame followed by a kind of awe.

As far as poetry itself goes, the title piece of the next section, “Report a Problem,” concludes that “You could report a problem with this poem, / but all the advice (an industry in itself) says / don’t bother, this poem is busy growing / its sainted neurons, it doesn’t need your / interference ….”

The next section is titled “The Long Box” (coffin? horse trailer?), and in the first poem, “After Lorne,” we wait in a medical waiting room while Lorne tells us “If nothing happens, / you gotta investigate. That’s what it means to be a Marine.” In “Mercury Tours,” a daughter, nearly grown up, is seen off on a bus with a prayer to the Roman god of change: “O / deity of hastening, messenger of speed—” and three poems later, we find a long-term couple camping out in western democracy. Here’s the entire “Couple”: “If only she could lift / the tarp of his resentment, / to see what’s underneath. // But it’s a solid tent, / staked tight. Perhaps because, / after all, it’s only a tent. ” Something awful (in the biblical sense of that word) is coming, Bruck seems to be telling us. The patriarchy is thinning. Shelter is provisional, and flimsy, in the world of symbol and in the real world, for those of us who live outside of privilege and those who do not. A child delirious with fever, longing “To Bring the Horse Home,” ends the section and we arrive at the next, “Tight Situations with Large Ships,” and the poem, “Peeling the Wallpaper,” in which the same child is “possessed to peel the paper with my nails, / to reveal the underlying glue….” The roll of wallpaper used to patch things up in the childhood home and carried by the mother “through four moves and fifty-plus years” is found “on her closet’s deepest shelf.” This picking off the surface to get down to what’s underneath, this carrying of material by a mother over time, then sorting out what it all might mean, gets close to this writer’s essential preoccupations.

The final poem of the book, at the far side of the bridge that opened “Maps,” contains the chilling question that likely comes at twilight and, like the end of all good fairy tales, is easy to read on a number of levels. The section is “Small Largesse,” and the poem, about another horse, is “The Situation”:

We brought oats to catch the horse,

but the horse was gone.

Did the horse take the opening

or did the opening take the horse? How long

do we stand here, banging on the pail?

So, lovely animals, sad people, lost animals, brave people. Simple words that tend to melt away in favour of a well-drawn and concrete scene and, often, an in-poem commentary on the scene. Stream of consciousness is reined in, and the line-by-line moves are more like controlled turns or careful leaps over familiar hedges and barriers.

—Michael Kenyon