Reviews

Poetry Review by Emily McGiffin

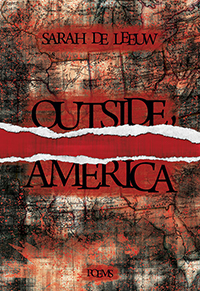

Sarah de Leeuw, Outside, America (Gibsons: Nightwood, 2019). Paperbound, 96 pp., $18.95.

As with her previous two books of poetry, Sarah de Leeuw’s Outside, Americadraws inspiration from the vast geographies of the North American continent and the resonant particulars of place. The book’s two eponymous sections unfold in the American heartland and the hinterland beyond it. Outside takes us to Niagara Falls, to Herschel Island in the “Far-off North” of the Beaufort Sea, to Smithers, and Nootka Sound. Americamoves from the edge of Port Angeles to Oklahoma to Arizona, from Brooklyn to Idaho to Florida. Throughout, the terrain is lively and shifting, marked by fault lines, debris flows, and metropolitan wildernesses alive with spiders, racoons, coyotes, and foxes. Yet if these landscapes are active and lovely, they are also sombre and bittersweet. The closing stanzas of “October Chanterelling,” the book’s second poem, read

As with her previous two books of poetry, Sarah de Leeuw’s Outside, Americadraws inspiration from the vast geographies of the North American continent and the resonant particulars of place. The book’s two eponymous sections unfold in the American heartland and the hinterland beyond it. Outside takes us to Niagara Falls, to Herschel Island in the “Far-off North” of the Beaufort Sea, to Smithers, and Nootka Sound. Americamoves from the edge of Port Angeles to Oklahoma to Arizona, from Brooklyn to Idaho to Florida. Throughout, the terrain is lively and shifting, marked by fault lines, debris flows, and metropolitan wildernesses alive with spiders, racoons, coyotes, and foxes. Yet if these landscapes are active and lovely, they are also sombre and bittersweet. The closing stanzas of “October Chanterelling,” the book’s second poem, read

two red cedars, twins attached

at ankle and neck, when one falls the other

will crumble; so my father is also saying

listen, I will die one day too: look.

The lines point toward the pairings and partings that shadow the collection: nostalgic moments in the long lives and afterlives of relationships; siblings separated by a continent and an ocean; the death of a father and the life of the child that goes on long after, carrying the memory of time shared. Veins of grief run through the book, bringing a pulsing arterial life into sharp relief and revealing the synchronicity and harmony hidden within the ordinary. To cite one captivating instance, “Found. Behind.” is an intimate portrait of twenty-one objects found at different points around the city of Prince George, for example: “Toque. Green. Hand-knit. Orange and yellow pompom. Stiched letters reading ‘Grandma’s / Love’ in black. Frozen to concrete. Middle of road. Early evening. November.”

At first take, the poem reads like an offbeat set of lost and found ads, many of them for objects—a condom ring, a used Band-Aid, a crushed McDonald’s milkshake cup—that the original owners clearly don’t miss. Yet in listing the objects with the careful detail of their setting and the time of their discovery, the poem nudges at a series of questions: what do we value and what do we cast aside? What are the lives behind objects and what traces of those lives remain? The objects themselves offer brief glimpses that are often startlingly intimate: a cigarette filter is stained with purple lipstick. Underpants bearing a Spider-Man motif are ripped to the waistband. The care with which the registry of urban detritus is compiled renders these mundane details extraordinary, demanding closer attention to the particularities of the world. The poem strikes me as emblematic of a collection that unfolds as a constellation of distant and seemingly unrelated instances and events. Together, these poems examine our precarious place within an ailing environment on which we are deeply dependent. “What Women Do to Fish” calls out the cumulative environmental hazard of such seemingly innocuous substances as exfoliant and birth control pills while “Drone Notes on Climate Change” depicts tens of thousands of beluga whales gathering for their southerly migration.

The collection departs from the intensely thematic orientation of de Leeuw’s previous work. Unlike her earlier books of poetry—both book-length poems with a sustained engagement with theme and form—Outside, Americais a varied collection. While thematic threads run through the gathered poems, the collection as a whole moves through a range of ideas and styles, drawing together an orca and Air Asia flight 8501, an Omura’s whale and a garter snake coiled inside a can of cranberry sauce. It looks with deep compassion at the bereaved, splicing the very worst of human experience (“the death of your son / or the news your only hope rests in a double mastectomy”) with the body of land:

It’s nearly impossible to squash

back sobs, all those little lakes,

muskeg bogs below, highways

leading to glaciers.

Something like flesh, a pattern.

Some poems felt less carefully developed. “A Short List of Things I Suspect Americans Do Not Associate with Britain that I Consequently Love All the More” offers a lighthearted list that seemed an afterthought or appendix within a collection oriented toward deeper layers and insights. “Oklahoma,” a set of five poems interspersed through the second section, gestures toward the displacement of Indigenous peoples throughout much of the eastern United States to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. In the fourth poem in the series, the diction breaks down into two columns of compound words and phrases that read like a call and response, before returning to regular syntax in the final section. Given the importance of the historical events, I wished for a stronger connection between the title and the content and for a sense of the imperative behind these syntactical and stylistic shifts.

Yet such questions and quibbles are minor in this solid and thought-provoking collection that draws a web of connections among the stuff of twenty-first-century North American life, the landscape it unfolds on and the many creatures who inhabit it. Speaking from the heart of metropoles and rural peripheries around the continent, the book’s restlessness evokes the modern condition and the all-too-common nature of contemporary relationships separated by oceans and mountain ranges. Through landscape the poems draw us toward an awareness of deep time and the preciousness of our singular moment within it. Bleached coral will eventually become sand, islands will emerge and recede as the sea, rising and falling, goes on without us.

—Emily McGiffin