Reviews

Poetry Review by Kyle Flemmer

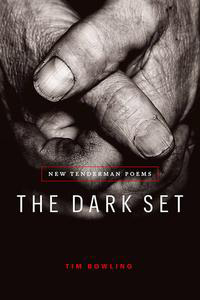

Tim Bowling, The Dark Set: New Tenderman Poems (Hamilton: Buckrider Books, 2019). Paperbound, 70 pp., $18.

In The Dark Set: New Tenderman Poems, Tim Bowling writes about the figure of the tenderman, a subject first taken up in his 2011 book, Tenderman. His topic, and the addressee of many of these poems, is the crew member of a fishing vessel, a character symbolizing down-to-earth, working-class ideals from bygone days. The epithet also evokes the sensitivities of the poet, a “tender man” in his own right. This new book revisits many of the same central themes as Bowling’s previous volume, including the tension between the blue-collar fishermen about whom Bowling writes and the white-collar subject position of the poet, a tension intensified by the struggle of actual tendermen. The depletion of west-coast salmon stock, due in part to overfishing, has led to a partial collapse of the industry that depends on it, and this collapse, of course, takes workers, their families, and communities down with it. “The man who commits / to a woman or a worker and expects something for something,” Bowling writes in “Lockout,” “has gone the way of the coho and the great white sturgeon.” The tenderman is a disappearing species, succumbing to the pressures faced by labourers in many resource industries. Implicit in the continuation of this project is an examination of the consequences of losing resource industries through mismanagement, especially for those whose livelihoods have been compromised. In fact, Bowling has dedicated The Dark Set to “all those still fighting to win basic workers’ rights.”

In The Dark Set: New Tenderman Poems, Tim Bowling writes about the figure of the tenderman, a subject first taken up in his 2011 book, Tenderman. His topic, and the addressee of many of these poems, is the crew member of a fishing vessel, a character symbolizing down-to-earth, working-class ideals from bygone days. The epithet also evokes the sensitivities of the poet, a “tender man” in his own right. This new book revisits many of the same central themes as Bowling’s previous volume, including the tension between the blue-collar fishermen about whom Bowling writes and the white-collar subject position of the poet, a tension intensified by the struggle of actual tendermen. The depletion of west-coast salmon stock, due in part to overfishing, has led to a partial collapse of the industry that depends on it, and this collapse, of course, takes workers, their families, and communities down with it. “The man who commits / to a woman or a worker and expects something for something,” Bowling writes in “Lockout,” “has gone the way of the coho and the great white sturgeon.” The tenderman is a disappearing species, succumbing to the pressures faced by labourers in many resource industries. Implicit in the continuation of this project is an examination of the consequences of losing resource industries through mismanagement, especially for those whose livelihoods have been compromised. In fact, Bowling has dedicated The Dark Set to “all those still fighting to win basic workers’ rights.”

Bowling’s concern for the tenderman way of life is reminiscent of Leslie Kaplan’s Excess –The Factory, of Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” and even of Bruce Springsteen’s The Ghost of Tom Joad. These texts, The Dark Set among them, tell the story of their wider political moment through lyric narrative, often by examining the narrators’ relationship to the workers. For Bowling, the tenderman is both a mirror and a myth, the poet’s “way of wrestling with [his] own conflicted feelings about masculinity, history, citizenship and power,” as stated in the expository paragraph on the first page. There is a clear and essential separation between the poet and his tenderman character that gives Bowling the room he needs to both empathize with and interrogate his subject. In doing so, Bowling draws in material from lived experience—anecdotes, impressions, memories, current events—and overlays it with the tenderman archetype, chasing out the gaps and overlaps. Is the backcountry fisherman compatible with cellphone culture? What is the tenderman’s attitude toward celebrities? And what do tendermen think of all this ink spilled in their name?

Many of the questions raised create productive opportunities to reflect on issues central to the tenderman project. For example, The Dark Set provides something of a critique of masculinity, though Bowling’s attempts to grapple with the dilemma of a man critiquing maleness have mixed results. “Tenderosterone,” a visual poem transforming “LIFT WEIGHTS” into “LUFTWAFFE” is highly successful, if the only poem of its kind in the book. “Interview with a Teenaged Daughter” is less so. This poem brings the speaker to the brink of (self-)examination with a “creep radar,” then turns away, becoming instead a statement about the trials of fathering a daughter, like “breathing eyes-wide-open / underwater.” Female characters, few and far between in The Dark Set, are generally conjured as foils for men. “Women, Eden. (Poets know where I’m going with this.),” Bowling writes in “Splitting the Chromosome, Driving the Lane.” Perhaps there is little room for femininity in the tenderman mythos, as may very well have been true of the now-hobbled fishing industry, and yet The Dark Set is unable to escape the structures it does earnestly scrutinize.

While I can appreciate Bowling’s willingness to bring his own history and class standing into play, this reviewer can’t help but feel there is more at stake than the author’s personal relationship to the tenderman figure. Issues of serious import (i.e., the over-consumption of natural resources and the disastrous consequences this can have on the very people who extract them) are just a pretext to further explore the author’s particular subjectivity within a political framework, rather than the other way around. By way of contrast, take Springsteen’s “Youngstown,” which charts the rise and fall of a company town through the intergenerational story of a working-class family. Though intensely personal, the story of Youngstown is tied directly to its political moment, from the triumph of the North in the American Civil War to the utter failure of American interventionism in Vietnam. Springsteen’s investment in the specific individuals who establish the town opens a portal onto the tragic and ugly history of America. Whitman too exceeds the personal: “Song of Myself” may be self-celebratory, but it is so to such a radical degree that love of the self spills over to include love of all others, especially the anonymous workers toiling to make the world. Bowling’s “Open Mic on the Government Wharf” is the standout poem in this regard, elegizing the working class while remaining authentically personal. “Tenderman,” Bowling writes, “there’s no work here. Tell the audience what you’ll be reading.”

—Kyle Flemmer