Reviews

Fiction Review by Kate Kennedy

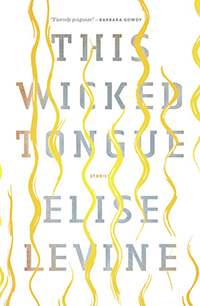

Elise Levine, This Wicked Tongue (Windsor: Biblioasis, 2019). Paperbound, 172 pp., $19.95.

This incredibly varied collection, Elise Levine’s second, is a series of departures, reinventions, and reckonings. Some of the most challenging stories, narratively, contain the most memorable voices and images, while what seem to be more straightforward narratives from the outset often turn out to be anything but.

This incredibly varied collection, Elise Levine’s second, is a series of departures, reinventions, and reckonings. Some of the most challenging stories, narratively, contain the most memorable voices and images, while what seem to be more straightforward narratives from the outset often turn out to be anything but.

It is perhaps telling that my favourite story of the twelve in this book, the last, “Alice in the Field,” is also the one I had the most trouble getting a fix on. Let me put it more plainly. I don’t know what this story is about, but it is the one that stayed most vividly with me days after reading the collection: people moving through a landscape, a party reduced to its last member, hiking down through fog and snow, emerging from what I was quite certain was the medieval period onto a roadway where the narrator steals a car and passes by gas stations and a new airport. The jacket copy describes Levine’s characters as confronting “the abject aspects of their inner geographies, mining them for gems,” and this final story seemed to me among the purest instances of that. It begins, “After, we exited the mountain. Fog grizzled the road. The tins on our backs clapped.” Later: “That night we lit a fire and toasted Pretty’s tattered right foot.” Then: “A Great Lake later, we roasted M’s heart.” I came out the other side baffled and bewitched.

In “The Association,” Levine situates the reader almost immediately. Eleven-year-old Martin is calling his mother from a hotel room in Virginia Beach while on vacation with his father, a year or two after his parents have split up. Although she seems to need this conversation more than Martin does, his mother’s responses are controlled, “with the cool precision she might use on one of her patients.” But Martin has already begun to suspect his mother is not entirely in control and, as kids that age do, has begun to see how others see her. He has also become self-conscious of how they present as a pair. At a Thanksgiving dinner with relatives, “Martin’s aunts and other uncle attend to their innocent, stupid brats and it occurs to Martin that once again he and his mother are a childless couple set apart from the crowd.” All Martin wants is to be older, to be off to university and life on his own terms, but in the meantime he is eleven and, as he says to his mother during a tense moment in the car-ride home from Thanksgiving, “you have the controls on your side.” It’s about doing up the windows, and quite a lot more.

Levine picks up Martin’s story again in “As Such.” Martin is now grown up, in infrequent contact with his mother but re-examining his relationship with her as he and his partner, Will, discuss having children themselves. While I welcomed the return of Martin, whose thought process slaloms between tidy, perfunctory assessments drawn from his mother’s manner and the “fucks” and “bullshits” borrowed from his father, I found this second instalment played it a bit too safe, with its conscientious reminders of what has brought Martin to his current situation. I would have welcomed some of the ambiguity Levine permitted in “The Association” as we find our place in the chronology of Martin’s life, figuring out how it does and does not line up with his sense of mastering it.

Time passing and coming back to us is a phenomenon that runs through the collection. In “Death and the Maidens,” Edwin, patriarch of a Jewish family in Saint John, NB, “is eighty-seven, fifty-two, thirty-five, and somehow nine and seven,” as he recalls the women in his life, his grandmother, his two wives, his daughter. His memories of his first wife are explained as something of an interruption in his experience of the present: “This wife dies and dies alone for nearly nine years after her death. Then her boat drifts from this story.” The story opens and closes with the boy he was walking with a bundle of hens in his hand, the hens banging against his legs, interrupting his gait.

Edwin is not especially likeable, but his frustration with his female relatives has a brightness to it. Indeed, throughout the collection some of the most vivid emotions are the forms of dislike, the sensation of being at odds. In “The Riddles of Aramaic,” a divinity student on a work term at a hospital fails to make a connection with the spouse of a cancer victim and almost thrills in spotting the moment her client decides not to trust her. And in “Money’s Honey,” a pregnant teen hitches a ride south with a man she despises to an oddly charming degree.

What delighted me most, though, across the collection was Levine’s lyricism. Her prose is full of half-rhyme and such earthily satisfying lines as “We snailed on until a stray palm snaked into view,” “Remember the Lord is a long-held note,” “Gulps of gull soup,” and “bats slopping through the heliotrope twilight.” In less capable hands, lyrical moments in fiction can feel like flourishes not tied by any sense of necessity to the meat of the story. In This Wicked Tongue, they present a belief system, a means of staking a throughline in what can sometimes seem like a chaos of old experiences and new ones amid the sensory barrage of the present.

—Kate Kennedy