Reviews

Fiction Review by Cynthia Flood

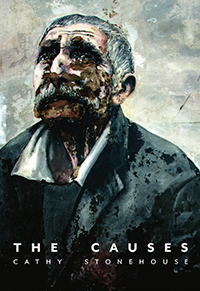

Cathy Stonehouse, The Causes (St. John's: Pedlar, 2019). Paperbound, 224 pp., $22.

One of the best Canadian novels of 2019, The Causes tells the story of Jose Ramirez, a young Argentinian fighting in the Malvinas War of 1982. Then, UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher set out to reassert British power in the face of Argentina’s attempt to repossess these Atlantic islands. They’d “belonged” at various times to Spain and France, but Britain had controlled them since the 1880s.

One of the best Canadian novels of 2019, The Causes tells the story of Jose Ramirez, a young Argentinian fighting in the Malvinas War of 1982. Then, UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher set out to reassert British power in the face of Argentina’s attempt to repossess these Atlantic islands. They’d “belonged” at various times to Spain and France, but Britain had controlled them since the 1880s.

Canadian writers have created fine novels about war—to name only three, Timothy Findley’s The Wars, Joseph Boyden’s Three-Day Road, Michael Ondaatje’s Warlight. Cathy Stonehouse’s The Causes matches these in quality. Like them, it’s not a quick read, but given the present state of the world, the book demands attention. Also required: a willingness to let the living narrative take you (and figure things out later).

An early scene: Midnight. Jose lies on icy mud, tied to stakes crucifixion-style. A Brit soldier, photographing the Argentine dead, steals Jose’s boots. His feet freeze. Then a man wearing skins appears with a wolf, or dog, and cuts Jose’s ropes with a shell-bladed knife. An explosion sounds, animal and man run off, and Jose’s alone till he hears his father reading about Achilles from the Iliad. A friend, Miguel, arrives to breathe life into him. Later, in hospital, Jose recognizes the thief, also finds and keeps a photo of a small boy and girl.

This battlefield scene embodies the novel’s major themes: political violence, love, art. On the Malvinas, imperial settlement has wiped out all indigenous mammals, including the wurrah or dog/wolf, while Argentina’s own right-wing politics destroy Jose’s family among thousands of others. In Jose’s early teens, his mother Rosa silently adapts to the repressive regime; his father Carlos, a professor and writer, won’t. Watching them quarrel, teenage Jose sees two “endangered mammals.” In 1977 Carlos is disappeared, his books and papers destroyed. Jose draws, to endure grief.

Because the dead reappear in memory, the reader often witnesses two time-sequences at once. Jose’s loving father Carlos turns up often, as himself but also as a hate-filled parody, a man named Ulises Pereira, who tries to defeat Jose’s purposes. At times Jose “does not know where he [himself] is from, or where he lives, his life rewinding and repeating like a spliced documentary.” Stonehouse’s style, an austere realism, contributes to that effect. Throughout, the writing’s vivid, clear. Simple declarative sentences abound, many not long, noun verb, noun verb. Adjectives and adverbs never appear in profusion. Paragraphs vary in length, though long ones are rare. Often, the rapid scenes create the effect of a film screening.

The Causes also features a rarity in modern fiction: illustrations, purportedly by Jose Ramirez, between Parts One and Two. They include an Antarctic wolf seen in 1890, a bear-woman, Miguel’s suicide note. While reading and re-reading, I returned often to these pencil drawings. Perhaps they form Jose’s essential images, luggage he has to carry when, in Part Two, he leaves Argentina in hope of healing.

Post-war, Jose’s hospitalized with necrotic hands and feet, yet “makes loose sketches in ballpoint pen.” Once home, in a country wounded by failure, he sharpens a pencil. “They have lost the islands and there’s a wolf inside him, but for now the only question is what to draw.” As his nightmares continue, making images helps Jose to live again. But—how not to kill, die? He works as a cook (weapons all round), a graphic designer (layout knives), an illustrator of medical brochures (blood, guts everywhere), later in a shoe store, a meat freezer, a bookstore. Always he draws. Much later he spray-paints buildings with a blue fox, horses, seabirds. His signature: La Bomba.

Jose’s first girlfriend, teenage Gaby, before the war acts as his model. “With every mark, her contours shape his art.” He draws, draws, draws. To do so: essential. Their love affair doesn’t last long yet she’s permanent in him. Other lovers too remain important, in memory or fantasy. Only English Jane stays real, however. Jose meets her in London during travels undertaken so as not to succumb, to die. Though Jane’s the sister of the Brit who stole his boots (yes, that photo), she and Jose grow close. They never live together but across thousands of miles their correspondence endures.

Male connections are also valuable. Jose’s rescuer Miguel reappears, seriously disturbed. A friendship forms, love’s possible—but Miguel commits suicide (among 459 Argentine veterans of the Malvinas War to do so). Jose takes the ashes for burial to the continent’s southern edge. Later, at a veterans’ meeting, he reconnects with Daniel, a high-school friend perhaps less damaged by the war. A hopeful note? But Jose’s mother marries a wealthy businessman. Rosa says, “Josito, I’m looking to the future. How else do we get over the past?”

Good question.

Near the novel’s end, Jose returns to the Malvinas with his lover Ines to lay out 649 small stone memorials, one for each killed Argentine, Miguel included. The two watch penguins on a beach “resting against each other, or twitching their heads around gently as if to taste the wind.” Jose wonders why the explosives hidden everywhere don’t kill them. Ines explains, “They are too light. Lighter than children.”

—Cynthia Flood