Reviews

Poetry Review by Dallas Hunt

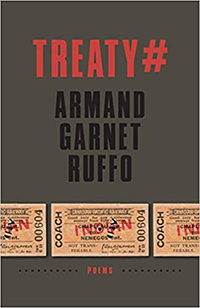

Armand Garnet Ruffo, Treaty # (Hamilton: Buckrider, 2019). Paperbound, 112 pp., $18.

Armand Garnet Ruffo’s newest collection of poetry, Treaty #, is arranged in a tripartite structure: the first, “Impetus Ungainly,” charts some of the book’s driving themes, while the second, “Travelogue Sightline,” catalogues a speaker (most likely Ruffo himself) travelling throughout the world, commenting upon what they witness; the third section, “Boreal Investigative,” finds middle ground between the two, staying within the intimate pockets Ruffo has carved out in the first section, as well as journeying outward, as the speaker does repeatedly in the second section. Interestingly, each section begins with text from a Numbered Treaty (Nine, One, and Five, respectively), with most of the words reversed, except for a few choice words that illustrate the underlining ideologies, imaginaries, and intentions subtending the treaties as negotiated by white settlers. The text to Treaty One, for instance, is mostly reversed, but with a handful of striking words left as they appear in the original document: “Benevolence,” “Subjects,” “white,” and “Cash in,” being just a few examples.

Armand Garnet Ruffo’s newest collection of poetry, Treaty #, is arranged in a tripartite structure: the first, “Impetus Ungainly,” charts some of the book’s driving themes, while the second, “Travelogue Sightline,” catalogues a speaker (most likely Ruffo himself) travelling throughout the world, commenting upon what they witness; the third section, “Boreal Investigative,” finds middle ground between the two, staying within the intimate pockets Ruffo has carved out in the first section, as well as journeying outward, as the speaker does repeatedly in the second section. Interestingly, each section begins with text from a Numbered Treaty (Nine, One, and Five, respectively), with most of the words reversed, except for a few choice words that illustrate the underlining ideologies, imaginaries, and intentions subtending the treaties as negotiated by white settlers. The text to Treaty One, for instance, is mostly reversed, but with a handful of striking words left as they appear in the original document: “Benevolence,” “Subjects,” “white,” and “Cash in,” being just a few examples.

In this way, the text resonates with an erasure poem from the most recent collection of Cree poet Billy-Ray Belcourt, NDN Coping Mechanisms, wherein Belcourt blacks out a majority of the text of Treaty Eight to highlight the ongoing ramifications of the document and the effects it has on everyday life for Indigenous peoples in that territory. Treaties, it would seem, read more precisely, clearer, when stripped of the window-dressing of British/Canadian legalese; in this way, the intentions of their negotiators (acting on behalf of colonial nation-states) become glaringly apparent.

As the descendant of “signatories to the Robinson-Huron Treaty of 1850,” Ruffo is intimately aware of what it is like to make a life out of the afterlife of a Treaty gone bad—that is, out of a Treaty repeatedly broken by its European signatories. The poems in the collection extend outward from these duplicitous documents into the present, with Ruffo documenting the quotidian frustrations of ordinary life, including an ant infestation that resembles the unending encroachment and trespassing of white settlers. In many ways, Ruffo’s collection is a repository of the cascading set of events and processes that transpire when one is coerced, both explicitly and implicitly, to sign with an “X” on a Treaty document. Indeed, as Ruffo sardonically asks in editorializing parentheses inserted directly after one of these “signatures”: “What does x mean anyway”?

Ojibwe scholar Scott Lyons describes the “x-mark” as a “coerced sign of consent made under conditions that are not of one’s making,” signifying both “power and a lack of power, agency and a lack of agency.” For Lyons, an x-mark refers to the way in which some communities signed treaties under duress and coercion, marking or signalling their “agreement” to treaty negotiators with the mark of an x on paper or parchment. Elaborating on his theory of an x-mark, Lyons states: “It is a decision one makes when something has already been decided for you, but it is still a decision. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. And yet there is always the prospect of slippage, indeterminacy, unforeseen consequences, or unintended results.” We see evidence of these “unintended results” when Ruffo, an Indigenous body marked (“intended,” one might say) for destruction, travels the world and visits Cuba and Japan. Through the processes enabled by the asymmetrical relations instantiated by documents like Treaties, people like Ruffo are in many ways no longer supposed to exist. And yet Ruffo and the web of relations he is situated within are still here, in the face of constant violence, such as “Columbus’s sword” or “Duncan Campbell Scott’s Indian policy.”

Ruffo, then, exists in spite of these violent processes, in spite of what these x-marks “have wrought.” But let’s be clear: the signatories who marked their “consent” with an x-mark “have wrought” nothing; rather, the active and ongoing destruction of Indigenous social and political life is attributable to settler colonialism and its beneficiaries. Nonetheless, the speakers in Ruffo’s poems find moments of joy and glee—they go on road trips, attend awkward dinner parties, and are transfixed by fireflies in Oklahoma. Ruffo illustrates a world wherein “the collision of histories leaves us all crawling,” the echoes of x-marks dictating the ways in which Indigenous peoples are inhabiting and can inhabit what is currently called Canada. However, Ruffo does not close the door here, but rather gestures to “the day the world begins again.” Perhaps this day will arrive when the “true intent” of treaties is adhered to, which is to say when good relations between peoples are actually enacted, and an agreement whose terms should be subject to constant renewal are not mobilized as a roadmap for cessation, surrender, and settlement. If this day never comes, we might all be “witness to the inevitable reckoning” of endless consumption and accumulation, as the desire for “always more stuff” comes at the expense of the world we inhabit and are in relation to.

—Dallas Hunt