Reviews

Fiction Review by Jane Shi

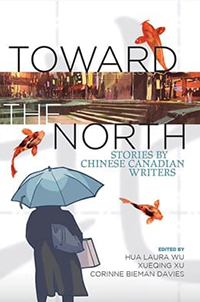

Toward the North: Stories by Chinese Canadian Writers, edited by Hua Laura Wu, Xueqing Xu, Corinne Bieman Davies (Toronto: Inanna, 2018). Paperbound, 302 pp., $22.95.

Toward the North is a banquet of literary aunties and uncles who have all signed up for short-story karaoke. Their sharp, tender, and freedom-seeking voices crackle and simmer in the loneliness (and stench!) of an empty house, in uncanny bushes of Ontario’s suburban gardens, and beneath an ominously beautiful aurora borealis sky. Imagine the karaoke wedding scene in Lulu Wang’s The Farewell with twice the drama, scandal, and gossip.

Toward the North is a banquet of literary aunties and uncles who have all signed up for short-story karaoke. Their sharp, tender, and freedom-seeking voices crackle and simmer in the loneliness (and stench!) of an empty house, in uncanny bushes of Ontario’s suburban gardens, and beneath an ominously beautiful aurora borealis sky. Imagine the karaoke wedding scene in Lulu Wang’s The Farewell with twice the drama, scandal, and gossip.

Reading these stories humbled me deeply: they emerge from a specific era within recent Chinese Canadian immigration history that I rarely get to engage with as a literary interlocutor despite having been a part of it. Each protagonist hails from mainland China, their pinyin names standardized from a post-1950s People’s Republic of China where Mandarin has become the lingua franca. Translated into English, these stories revisit transitional spaces familiar to me from my own childhood (passenger airplane, homestay basements, and empty houses) with both precision and the brow-knotting pressures of grown-up discernment.

Despite the generality of the term “Chinese Canadian Writers,” this anthology captures the literary ethos of my parents’ generation. It offers English-speaking readers a window into the clumsy, awkward, and painful struggles and joys of first-generation immigrant parents who raised 1.5-generation millennials like myself (who arrived in Canada as children) and many of my second-generation peers. The narrative range, emotional depth, and back-cracking humour of these stories are made more profound within this readerly context. I am invited to sit at the adult table of the banquet in a bustling restaurant in North York, imagining myself as the many children within these stories—Wenwen, Millie, or Xiaoyue—as I await my turn to speak.

As Jasmine Gui perceptively notes in her review in Looseleaf Magazine, this anthology focuses on the banalities of everyday life: purchasing homes, finding a job, learning English, seeking love, maintaining a marriage, and raising children, all while finding one’s footing in and translating oneself across an incongruent cultural landscape. Except for Daisy Chang’s “Little Weeping Millie,” which focuses on the grandmother, these stories capture the viewpoint of a generation on the go. Often new parents in turmoil from relationship or marital strife, the characters wriggle for shortcuts, walk away from heartbreak, and make bold choices towards freer lives. Inheriting histories of poverty, war, and secrets, they struggle to leave their pasts behind them and learn to adjust to new possibilities and expectations.

Subtle and explicit feminist interventions struck me throughout this anthology. Whether poking fun at filial expectations in Yuanzhi’s “Jia Na Da/Canada,” the meditation on independence in Ling Zhang’s “The Abandoned Cat,” the portrayal of pathetic and desperate men in Tao Yang’s “An Elegant but Stiff Neck” and Bo Sun’s “Surrogate Father,” or direct engagement with domestic violence in Yafang’s “The Vase” and Chang’s “Little Weeping Millie,” these critiques draw a through line of resistance across generations of Chinese women in the diaspora, connecting the anthology with the first Chinese Canadian novel, SKY Lee’s Disappearing Moon Cafe.

As it did for Gui, the final, titular story, Ling Zhang’s “Toward the North,” raised questions for me about how Han Chinese settler authors navigate their positions on occupied lands on both sides of the Pacific. After the death of his parents, mixed Tibetan-Ojibwa deaf boy Neil finds a new father in Zhongyue, who teaches him sign language as a hearing rehabilitation instructor. While both Neil and his Tibetan mother Dawa are seen through Zhongyue’s empathetic, caring eyes, the power dynamic between them is never addressed. Seamlessly able to act as both guardian and teacher for Neil as well as support other deaf children of Sioux Lookout, Zhongyue is called to work on the Reserve by a Communist song from his childhood, beckoning him to go towards the north, ultimately to enact another stage of his career. His heroics mask his failures back in Toronto, where his mother covers his carpet in his home in a trail of ash and rebuffs his remittance, his wife leaves him for another man, and his daughter Xiaoyue sees through her parents’ unhappiness. Neil’s alcoholic father Joy, who inherits not his own father’s knowledge of traditional Ojibwa medicines but rather the violence of patriarchy, is the antagonist of “Toward the North.” Despite offering glimpses of connection and longing in Dawa’s and Joy’s affinity for herbal medicines on their respective territories, the story does not probe the colonial roots of Joy’s patriarchy. While the story links Zhongyue’s own waywardness to his experience of intergenerational poverty, Joy’s criminality and alcoholism hang on him like a character flaw. He is never quite afforded the same grace nor interiority.

The strength of this anthology ultimately lies in its ambivalent depictions of immigration. One of my favourite stories, Shiheng’s “Hana No Maru,” offers us the comical image of restaurant worker Husheng dozing off in a Japanese café after confessing his lofty get-rich-quick plan of marrying his manager and opening a restaurant in Hawai’i. Suspended in sleep, ethereal like a ghost watering a garden in He Chen’s “West Nile Virus,” this story hints at the bigger why of emigration, of dreams that loom, falter, and remain so.

Toward the North brims with desire for reciprocation across generations, languages, and cultures. Indebted to its what and its why, I look forward to future literary generations responding as fearlessly and unapologetically as the voices in this collection tell their stories and move forward in their lives.

—Jane Shi