Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Aaron El Sabrout

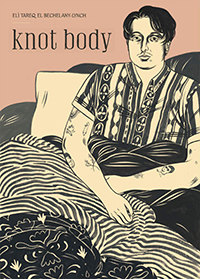

Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch, knot body (Montréal: Metatron, 2020). Paperbound, 108 pp., $17.

Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch’s knot body is a radically honest examination of the queer body, the disabled body, and the racialized body. In the poems, essays, and letters of knot body, El Bechelany-Lynch wrestles with the interrelationship of trauma, chronic pain, queerness, colonialism, and gendered violence with humour and generosity. They put on the lab coat of a doctor, exploring their own fibromyalgia diagnosis and imploring others to research the drugs they are put on—then turn around and point at the medicalization of trans people, the gendered nature of diagnosis, and the ableism of “cure.” The work cracks open form and queers it; each letter is part of an imagined correspondence but stands alone, and many pieces transform over page breaks from lyrical to confessional and from poetry to essay.

Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch’s knot body is a radically honest examination of the queer body, the disabled body, and the racialized body. In the poems, essays, and letters of knot body, El Bechelany-Lynch wrestles with the interrelationship of trauma, chronic pain, queerness, colonialism, and gendered violence with humour and generosity. They put on the lab coat of a doctor, exploring their own fibromyalgia diagnosis and imploring others to research the drugs they are put on—then turn around and point at the medicalization of trans people, the gendered nature of diagnosis, and the ableism of “cure.” The work cracks open form and queers it; each letter is part of an imagined correspondence but stands alone, and many pieces transform over page breaks from lyrical to confessional and from poetry to essay.

One of the preoccupations of the work is time, specifically the ways that folks our society considers disabled experience time differently. In a way, COVID days and lockdown life have given many a glimpse into disabled time, that time soup where “the days fog and blur.” El Bechelany-Lynch is an adept guide through this ocean of bed days. They invite us with generosity and warmth to their bed, “a new site for pain,” but “[n]ot in a sexy way, unless that’s what we’ve decided.”

The charming, easy address of the letters in knot body simultaneously beckons the reader and holds them at arm’s length. The letters never quite let us know if we are the “friends, lovers, and in-betweens” to whom they are addressed. “You who are reading this might not be the intended audience, though perhaps you might also be this intended audience.” The impression is of a permitted kind of flirtatious voyeurism. At one point the speaker invites us into their creative process in constructing the book—choice of genre, as well as how they “[m]ix around some random details and turn [them]self into a character, so far away from [them] that [they] can convince both you and [themself] that nothing bad has ever happened to [them].” The speaker admits that this “glaze of fiction” is because “I worry that in writing this, I am revealing too much.” As a reader, one sometimes wonders if they are seeing too much as well.

One of the analyses that the narrator, Eli, offers of their pain is based on the work of Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, an American psychiatrist and author of The Body Keeps the Score. The book, which Eli notes “is in the hands of every queer on the queerest bus in Montreal,” argues that traumatic experiences are held in the body’s somatic memory, so that if a person experiences abuse or violence it may have physical effects on their body throughout their life: “I forgot a memory but it came back so suddenly that it smacked me right back into bed.” knot body brings the somatics of pain to the fore in “Betsy,” a poem addressed to the “big bowling ball dyke knotting her way into my shoulder.” “Betsy” is a creation of trauma, “Betsy you’re hurting me / Betsy forgets / she isn’t trying to / hurt me.” They massage the knot, work it, acupuncture it, but try as they might they cannot get it to leave: “She won’t move until she knows where she’s going.” Likewise, they try to excavate the memory of trauma, but they can’t quite get to it. “We pretend it doesn’t exist but the impossible memory keeps reminding us it does. I scream please tell me, please tell me, please tell me. It ignores me. This is not how it works.” The memory is too traumatic, the memory is too big, the memory is rooted in generations of colonialism and gender violence.

The stone became a

bomb, and the bomb became a violation, and that violation was

passed on through red blood cells, through DNA, through

pain receptors present all over the body. Salvage our souls

and throw them back into the hourglass, do we return with our pain?

Ultimately, all that is left is the pain. El Bechelany-Lynch is a tender and careful raconteur of pain. Their approach is self-conscious, almost guilty at times: “I keep hitting command + F to make sure pain makes up less than 10% of my word count.” Still, the pain cannot be denied. The vulnerability and openness of pain in this work are a generous gift and a burden. The writing itself a kind of compulsion, an escape from the pain but also a part of it, reinforcing it: “I write and write until my brain folds, and the fog feels more like numbness than pain, more faded than my brain can stand.” And yet, what a beautiful wholeness emerges from such pain.

knot body expresses the hope that “maybe one day we’ll know how to love each other in all our dignity.” Indeed, it offers us a model of what that could look like. It shows us painful vulnerability, easy flirtation, and real moments of pleasure. knot body takes us by the hand, invites us to climb out the window and onto the roof (if we are able), and to witness the dawning of a kinder, queerer way to be together.

—Aaron El Sabrout