Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Bill Stenson

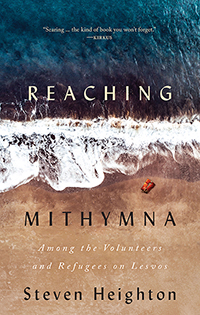

Steven Heighton, Reaching Mithymna (Windsor: Biblioasis, 2020).

Paperbound, 275 pp., $22.95.

Often, the source for a memoir comes from the author’s everyday life, but with Reaching Mithymna, Steven Heighton disrupted his routine to volunteer for one month in 2015 on the island of Lesvos, Greece, as close as 12 kilometres by water from Turkey, where thousands of desperate Syrians had gathered, hoping to make their way to Greece and eventually to northern Europe.

Often, the source for a memoir comes from the author’s everyday life, but with Reaching Mithymna, Steven Heighton disrupted his routine to volunteer for one month in 2015 on the island of Lesvos, Greece, as close as 12 kilometres by water from Turkey, where thousands of desperate Syrians had gathered, hoping to make their way to Greece and eventually to northern Europe.

An intriguing memoir—and Steven Heighton’s account qualifies—should inform the reader of an angle on a topic they may have some experience with, or of a topic most know little about, as is the case here. Several times in his writing, the author questions what drove him to embark on the journey: “I’m still not sure why I’m here, beyond a wish to do something useful, involving flesh and blood people instead of invented characters and words on a screen.” He meets Adonis, a soldier and the son of his host, who is incredulous at the author’s desire to help strangers. Adonis says, “That is not how people are. Always there is some other reason.” Heighton, at one point, considers that having been a writer for 25 years has “…roused a hunger for embodiment, belonging, rooted usefulness,” and that hunger may be his “other reason.” Whatever constitutes the driving force that led to Steven Heighton’s account, the resulting experience is engaging and illuminating.

Reaching Mithymna focuses on one tiny hot spot reflecting humankind’s institutional failure to organize a reasonable life. Steven Heighton arrives for his volunteer post four years after a 38‐year stretch of authoritarian rule in Syria flared into civil war. According to the bbc, there are 20 million refugees in the world, and 25 percent of them are Syrian refugees. As Heighton points out, “The Greek word for refugees, prosfyges, breaks down etymologically into something like toward‐fleers, or those fleeing forward” and the Syrians he encounters have made desperate attempts in overcrowded boats to get toward a better life. Many of them have not made it.

His volunteer work involves whatever it is he can do to help, and we experience Steven Heighton’s journey through the eyes of a wellintentioned neophyte, written with a poet’s nervy word choice and a fiction writer’s respect for narrative. After two days of arduous travel, a meal of mullet and ouzo, and a two‐hour nap, they thrust him into one of the many roles performed by volunteers. He works alongside volunteers that include translators, doctors, nurses, photographers, university students on summer leave, Seventh‐Day Adventists, goat herders, and Buddhists. The people he works with come from places like Germany, Norway, England, Wales, Israel, Canada, the USA, Sweden, France, Holland, and many from Greece. Their assignments include helping men, women, and children, often drenched and cold, to shore after making the journey that may have taken them one hour or three hours. The arrivals are warmed, clothed, fed, and registered. Because of language barriers and the frenzy of migration, the intimacy between the volunteers and the refugees is fleeting: “They’re coming surprisingly fast, like competitors in a long road race entering the home stretch…. Many look wet and chilled but their faces and postures

radiate relief, even joy.”

Several waves of people land at night to escape notice. They arrive in makeshift inflatables, often recycled and with tape covering holes in the boats sufficient that bailing during the journey leads to a happy ending. It does not end happily for all. Some are young and some are frail, and they come fitted with repurposed life jackets filled with scraps of bubble wrap and sawdust. Most of the boats hold 12 to 15 people safely and yet arrive with 40 to 60 refugees at a time. For most of Heighton’s stay he is busy, taking various shifts, but his time there is in the middle of winter. The summer before he arrived, as many as 100 boats a day floated to the shores of Lesvos, filled with the displaced who have paid up to $1200 for the privilege (half price for children) which, during the peak season, amounts to a $5‐million‐dollar‐a‐day business for the smugglers operating from Turkey.

Heighton’s observations on Lesvos range from the practical work of saving humanity to near tragedy. Elektra, his host at the inn where he stays, mothers him excessively. Fifteen minutes after showing him his room, she reenters with a bag of supplies because experience tells her, “The volunteer men never feed themselves properly.” She leaves him Greek coffee, pistachios, almonds, cheese, sardines, tomatoes, apricots, a bottle of ouzo, and three packages of Marlboros. Every time he leaves to volunteer she swoops into his room to tidy. When he secures his package of coffee with an elastic band, she replaces it with a brown clothes peg. The next day, for fun, he replaces the brown clothes peg with a green one, and Elektra, the following day, employs the brown clothes peg once again and takes away the green one. While working at various deployment centres, Kanella, a stray dog many find an inconvenient intrusion, weaves her way through the jostling crowds searching for the same things as the refugees.

Steven Heighton’s mother was of Greek heritage. Reaching Mithymna follows the same path taken in 1922 by Asian Greeks that, the author surmises, may very well have included his own relatives. The same play with a different cast of characters; “A century, it turns out, is a tiny thing.”

—Bill Stenson