Reviews

Poetry Review by Carol Matthews

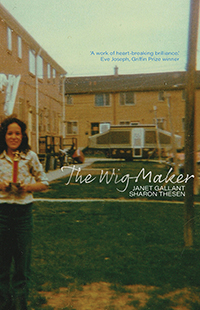

Janet Gallant and Sharon Thesen, The Wig-Maker (Vancouver: New Star Books, 2021). Paperbound, 97 pp., $18.

In recounting a lifetime of abandonment, sexual abuse, mental illness, suicide, loss, desperation, and healing, Janet Gallant and Sharon Thesen create a disturbing yet ultimately inspiring collaboration which is part biography, part memoir, part poetry, and part lament. The story is Gallant’s and the voice is hers; Thesen transcribes and transforms the narrative into a long poem. The Wig-Maker reverberates with echoes of moans—“I live in my mom’s moan” and “You never forget that moaning / Those deep, deep cries”—and those echoes linger with the reader, reminding us of the connection between moan and mourn. Thesen’s repetitions of Gallant’s words give the sense of keening at a wake.

In recounting a lifetime of abandonment, sexual abuse, mental illness, suicide, loss, desperation, and healing, Janet Gallant and Sharon Thesen create a disturbing yet ultimately inspiring collaboration which is part biography, part memoir, part poetry, and part lament. The story is Gallant’s and the voice is hers; Thesen transcribes and transforms the narrative into a long poem. The Wig-Maker reverberates with echoes of moans—“I live in my mom’s moan” and “You never forget that moaning / Those deep, deep cries”—and those echoes linger with the reader, reminding us of the connection between moan and mourn. Thesen’s repetitions of Gallant’s words give the sense of keening at a wake.

There are many ways to shape a personal memoir. It may emerge as non-fiction, creative non-fiction, or as fiction loosely based on personal experience. What matters is that the story be told, and humans have always wanted to tell their stories. In paintings on the cave walls at Lascaux, in the oral histories of indigenous people, the songs of Orpheus, the prophecies of Cassandra, the Norse sagas of the Middle Ages, and the tales of Jacob Grimm we find accounts that help us connect with others and understand more about our own lives and the world in which we live. We read and listen to stories in order to understand ourselves and what it means to be human. We recount our own stories so that they may become part of a larger fabric of human

experience and may offer guidance to our listeners.

In The Wig-Maker, we hear two storytellers speak together. It’s a sad story. Gallant’s father abuses all his children: physically, sexually and emotionally. He calls Janet for “tea‐time,” and when Janet takes the tea downstairs, he opens his fly. Afterwards, she goes back upstairs and brushes her teeth. With Gallant’s older sister, Penny, he has intercourse. He also brutalizes her older brother, Billy, beating him and throwing him about, and Billy utters “an animal‐like cry, a moan.” Eventually, Billy hangs himself in a closet with a bicycle hook. Soon after Billy’s suicide, Penny is “taken while drunk and impregnated with her first child.” Gallant’s early experiences with her father and the next‐door neighbour lead her into abusive relationships with older boys, believing “That’s what love meant.”

Despite her father’s horrific treatment of her and her siblings, Gallant wants to understand why he was such a monster. “Was it the military—or was it his own father—or was it the Church,” she wonders. She makes excuses for him, reflecting on the poverty of his childhood, his lack of education, the difficulty of raising five kids on a soldier’s salary, and searches to find something to appreciate in him: “My dad

could have given us away but he didn’t.”

Only three years old when her mother left, Gallant spends years trying to find her, asking questions and making cold calls to possible relatives. It is a labyrinthine journey which leads to loss after loss. When she finally tracks down and meets her mother she sees, not the Diana Ross she’d fantasized, but a three-hundred-and-fifty-pound vegetable who left her children and became a tramp. The losses continue. Penny dies, despite Gallant’s attempts to care for her. Gallant’s husband and father of her two children also dies suddenly and tragically.

At the end of her search, Gallant learns through a DNA test that the man who abused her was not her biological father. Instead, it appears that her actual father was a member of the family that lived downstairs. Perhaps as a result of the many shocks she has experienced, Gallant loses her hair and is diagnosed with alopecia, a condition which leads her to learn the craft of wig‐making.

Wig-making doesn’t figure prominently in this novel, but it is an important metaphor for the book. Gallant works only with temple hair which she buys from certified dealers, hair that is obtained from young women who offer it at Indian temples as a sacrifice. Each hair must be drawn through separately and about 80,000 individual hairs are required to make each wig. It sounds like painstaking work, resembling

Gallant’s process of pulling together the individual threads of her history. “Wigs, as we all know, are powerful transformational magic,” Thesen says in one of her explanatory notes. It’s true. We may wear wigs to create a new self or, as is the case with sufferers of cancer or alopecia, in order to recollect the self that was once there. In this book, Gallant does both.

At the end of her quest, Gallant knows who she is. Settled with her partner on the side of a mountain overlooking Lake Okanagan, she has Mindy, her bichonn shih tzu, her successful wig‐making business, and an important friendship with the neighbour who helps her tell her story. “It really was and will continue to be magical,” Gallant says, “this collaboration, this friendship.”

Gallant’s voice is clear and strong throughout the book. Thesen, an award‐winning poet, editor, and teacher, rightly known for her lyricism and imagination, listens and writes as Gallant speaks and together they weep. The result is an unforgettable duet.

—Carol Matthews