Publishing Tips

Submissions Fees R Us: To Pay or Not to Submit?

May's Publishing Tip (our first in a bimonthly series), written by past Malahat intern Matt Thibeault and editor John Barton, asks the questions many writers refuse to acknowledge: should we be paying to submit to literary journals?

The debate over charging a nominal submission fee continues to divide writers. The imposition of such a fee, however big or small, challenges their loyalty to the literary magazines that have started charging and shifts their expectations about the role these journals should now play in their writing lives. The controversy was already sufficiently contentious in December 2011 to attract the attention of the business magazine Forbes.

Spurred to investigate further after having read a more in-depth article in Poets & Writers, Forbes contributor John Farrell suggests that literary magazines justify charging a submission fee for online submissions because they “are struggling, and with the explosion of the Internet short story [and other] submissions from writers far exceed subscription rates, swamping already overworked and underpaid staff.” In 2013, the online writers’ resource, Writer’s Relief, sided with submission fees: “Small admin fees can help struggling literary journals stay on their feet—and that’s good for writers. If a journal’s ability to stay viable is dependent upon charging a very small submission fee, then we at Writer’s Relief would support an ethical practice. We hope you will too.”

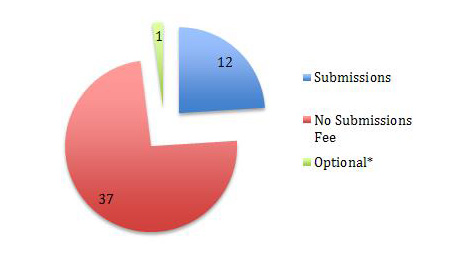

In a sample of 50 journals in Canada and the United States, The Malahat Review found that 12 now charge submission fees, 37 do not, and one has made the paying of a fee optional. 33% of these magazines that now accept online submissions charge submission fee.

Most magazines that have instituted a submission fee charge $3 or less; one (The Catamaran Literary Reader) sets its fee at an exorbitant $15. There does not seem to be any correlation between free submissions and magazines associated with universities; many publications directly linked to creative writing programs (e.g. PRISM international, The Harvard Review) charge submission fees. Nor is it surprising that those magazines with the most up-to-date or “modern” websites typically charge for submissions.

In April 2015, the Malahat conducted a seven-question survey to plumb writers’ feelings about submission fees. It promoted the survey on its website, in Malahat lite, on Facebook and Twitter, and on the list serves of the League of Canadian Poets and the Writers’ Union of Canada. Though the number of responses was small (100 writers completed the survey), the results are nevertheless revealing:

40% say, “I refuse to submit to magazines that charge submissions fees.”

30% say, “I pay the fee and submit my work begrudgingly.”

54% of the respondents stated that they have paid a submission fee before.

56% say they would not consider paying a voluntary fee when submitting.

Asked if they had ever paid a submission fee, 54% of respondents indicated that they had; 16% said that they had not, but would be open to doing so, and 30% emphatically said “No, and I never will.” Only 52% were aware that a portion of any submission fee would be kept by whichever platform (e.g., Submittable) hosted a magazine’s cloud-storage submission site.

The Malahat queried writers’ attitudes toward a policy of charging writers a fee to submit, which literary magazines increasingly find it necessary to impose. 39% of respondents felt that submission fees were equivalent to paying postage; 39%indicated they would never pay to have their work read; and only 9.5% felt that fees are necessary to accommodate the increasing workload that digital submissions fees create.

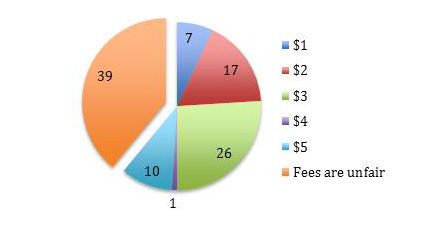

The most interesting responses are to question seven: “If you were made to pay a fee, how much do you think is fair?” Although 39% feel submissions fees of any form are unfair, 61% indicated that they consider some kind of fee to be “fair.” 26% feel a $3 submission fee is reasonable; 10% say that they would pay as much as $5.

One Facebook user commented on the survey post: “I'm fine paying submission fees to magazines that pay their writers. Recently, I've came across a few non-paying magazines charging fees and that is simply ridiculous. Those magazines should opt out of more expensive submission platforms and use email submissions instead. That they accept payment but do not give it [i.e., pay their writers] is disrespectful and unethical.”

When PRISM international introduced submission fees in 2012, the University of British Columbia-based journal reserved the $3 charge for online submissions only and continued to accept paper submissions for free. At the time, to pave the way for levying the fees, PRISM’s editors articulated their rationale for changing them on their blog:

“Online submissions are all about convenience. Convenience for you. For us, on the other hand, it involves a little more work and a little more cost. Increased costs include printing, postage, and labour. By charging a small fee—which, in most cases, is no more than the amount a submitter would have spent on paper, ink, an envelope, and postage—we can recoup those costs. Any small amount that may (or may not) be left over after our expenses will go to supporting PRISM’s printing costs. Something you can feel good about!” Read the full post here.

Room’s approach to submission fees is to keep the cost lower than average at $2.50 per submission and to encourage potential submitters to “think of this as similar to the cost of printing and mailing a submission” while still offering a free submission option for subscribers and “and low income writers.”

In her probing and still applicable article “The Price of Submission: The Evolution of Reading Fees and Their Cost to the Community” (Poets & Writers, November/December 2011), Laura Maylene Walter interviews literary-magazine editors from across the United States, where submission fees are much more commonplace. To a Canadian reader of her article, it’s clear that many journals south of the border see the fees as one key to survival in face of rising costs, unstable institutional support, and unreliable rates of subscription. The Massachusetts Review, for example, “has a circulation of about fifteen hundred, but receives twenty-five hundred submissions each reading period.” According to Aaron Hellem, the magazine’s editor, “It’s probably the challenge of every literary journal to bridge that disparity between its submitters and its subscribers, so they can find some kind of [financial] balance.”

In Canada, striking such a balance is probably less of a concern, but if the Malahat’s experience is similar to that of its Canadian peers, online submitting will change the way it operates. Submissions increased by 92% in 2014, the year it began accepting poetry submissions (in June) and creative nonfiction submissions (in October) through Submittable, in comparison to 2013. It will begin accepting fiction submissions online during the week of May 18, 2015. It had initially continued to accept paper submissions of poetry, but it phased them out entirely in October 2014 because the rate of receipt had decreased to the eight that were received in September. The Malahat used to receive up to 100 paper submissions per month.

The Malahat predicts that the number of submissions sent to it will increase by another 50% in the end of 2015. Unlike its American peers, it is less concerned about the disparity between the number of subscribers and the number of writers aspiring to publish with it than with the significant increase in workload and costs that online submitting creates. It now pays an annual subscription fee it to use Submittable (a cost it did not bear before) as well as the small honorarium paid to each of its editorial-board members. Because the number of submissions to be screened is growing rapidly, the editorial board is expanding in turn, which means its budget for honoraria must also increase significantly. Additionally, managing Submittable requires more editorial time because each submission must be assigned to be read by the editor. In the past, once paper submissions were logged and shelved by genre and according to the date received, editors came to the Malahat office to pick up submissions, taking only as many as they were able to read. All that was required to keep up the momentum was a friendly (if sometimes impatient) editorial nudge.

The Malahat has by no means made up its mind to start charging a submission fee, but unlike most journals, at least as reported in Poets & Writers, it will not be embarrassed to do so, if it must. As Jamie Swartz, the managing director of the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses, suggests, submission fees “are going to become more common and more accepted generally. It’s just the reality of the economics of literary magazines right now.”

Now for your Publishing Tip: If you find you must pay a fee to submit to a magazine, don’t think of it as a payment to be read, or as Roxane Gay, the editor of Michigan-based Pank (pankmagazine.com) suggests, as a payment for the right to submit. Rather think of it as a way of assuring that, like writers, editors are recognized financially in some minimal way for their work in service of your art and as a way to help guarantee that the “Beat the Clock,” jerry-rigged infrastructure, which keeps many a literary journal running, holds steady with more than a hope, a prayer, and literary duct tape.

* * * * * * * *

The Malahat Review posts “Publishing Tips” as a bimonthly guest column on its ![]() website and in Malahat lite. Follow it in order to learn how to improve your professional skills, from the writing of cover letters, to what house style means, to choosing a rhyming dictionary, to having an author photo (as opposed to a selfie) shot. If you have a Publishing Tip you’d like to share, email The Malahat Review at malahat@uvic.ca, with “Publishing Tip Idea” in the subject line. Tips should be 750 words or less. If yours is accepted, you will be paid an honorarium of $50.

website and in Malahat lite. Follow it in order to learn how to improve your professional skills, from the writing of cover letters, to what house style means, to choosing a rhyming dictionary, to having an author photo (as opposed to a selfie) shot. If you have a Publishing Tip you’d like to share, email The Malahat Review at malahat@uvic.ca, with “Publishing Tip Idea” in the subject line. Tips should be 750 words or less. If yours is accepted, you will be paid an honorarium of $50.