Looking for a Voice Accomplished and Original: John Archibald in Conversation with Mark Abley

Malahat advisory board member John Archibald talks with Mark Abley, the judge of our 2014 Open Season Award for Creative Nonfiction.

Tell us about yourself. Where do you live? Do you have a favourite place to write (either a room in your house or a place in your region)?

I live in a rambling house in Pointe Claire, a suburb of Montreal in what’s called the West Island. We moved there after the birth of my older daughter, who was extremely premature and who wasn’t coping well with the polluted air of the very trendy Mile End neighbourhood. Pointe Claire is not exactly an artistic hotbed, though neither is it one of those soulless subdivisions where every house looks like every other house. The St. Lawrence River is only ten minutes’ walk away from my home, and I often walk or ride my bike along the waterfront. In the far distance, on a clear day, you can see the Adirondack Mountains of New York state.

At home I work on a desktop computer in a cluttered upstairs office, surrounded by books and papers and assorted bric-a-brac. It has become almost impossible for me to write prose anywhere else. But I find it hard to compose poetry there. I write a lot of my poems when I’m travelling, scribbling first and second drafts on the back of whatever bits of paper come to hand. Travel sometimes manages to free my mind from the chores and obligations of everyday life.

Much of your writing pays special attention to the nature of human language. How did you become interested in this theme?

I can’t remember not being interested in language. Stray memories from childhood come to mind – how I consciously changed my accent, for example, a few months after my parents and I had immigrated to Lethbridge, Alberta, and my Grade 3 teacher said to the class, “Aren’t you ashamed that this little English boy knows the answer and the rest of you don’t?” Or how I was bemused, at about the same age, that the first name of the great hockey player Jean Beliveau wasn’t pronounced “Gene.” I suppose I realized at an early age that language was nothing to be taken for granted. I was also brought up a devout Christian, and the resounding sentence that opens the Gospel of St. John – “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” – always gave me a feeling of awe.

What writing projects are you working on right now?

My latest book of nonfiction – Conversations with a Dead Man: The Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott – has just been published by Douglas & McIntyre / Harbour. I’m also preparing a book of New and Selected Poems that Coteau will be publishing in 2015. Over the last decade I’ve written many columns about the English language, and I may try now to shape these columns into a coherent book. But that’s not a major project. Frankly I don’t yet know what my next major nonfiction project will be.

You are the judge for the Creative Nonfiction category of the Open Season awards this year. You have written in many different genres, what appeals to you about writing (or reading) creative nonfiction?

When I was a boy, my favourite book was a work of creative nonfiction – although in the late 1960s, nobody used that term. It was Gerald Durrell’s My Family and Other Animals, a loving and detailed and no doubt somewhat exaggerated portrait of the author’s life as a child on the Greek island of Corfu. I read it with enormous delight. What appeals to me today about creative nonfiction is, I suppose, what I instinctively recognized and loved in Durrell, even though I didn’t have the critical vocabulary at the time: a great variety of tones and registers, an ability to tell hard truths and poetic truths and occasional untruths in the same piece of work, and the tremendous freedom that the genre brings.

There are obvious challenges to judging a work of artistic expression. What do you look for in a successful piece of creative nonfiction? What properties would you hope for in the winning entry?

Much creative nonfiction, though not all, is about the writer’s own self, and especially if I’m reading a personal essay, I never want to find myself asking the awkward question “Why are you telling me this?” The telling will need to convince me and, with luck, move me. Beyond that, I’ll hope to observe a clear sense of form – to feel confident that the writer knew where to begin, how to proceed, and when to stop. And I will need to be convinced that the writer is adept at using the English language. That’s not as obvious a point as it may sound. A piece can be well researched, deftly structured and deeply felt, but if it uses words in a dull or awkward way, it should not win this particular prize. In short, I’m looking for a voice that is both accomplished and original.

How do contests like The Malahat Review's Open Season awards contribute to Canadian literature? What do they bring to an individual writer and to the writing community?

To the individual they bring validation, and this does not apply only to struggling or unpublished writers. Awards bring hope. Awards bring a confidence that the hard work has finally paid off, and that it will pay off again in the future. With an award like this in hand, it’s much easier for a writer to gain the attention of an agent or a major publisher. To the writing community at large, awards often bring new or neglected names to attention. I’m not overjoyed about the proliferation of literary prizes, but especially in a time when it’s harder and harder to make a living by writing, I accept the need to have some public recognition of quality; and I think the better awards – like Malahat’s – do exactly that.

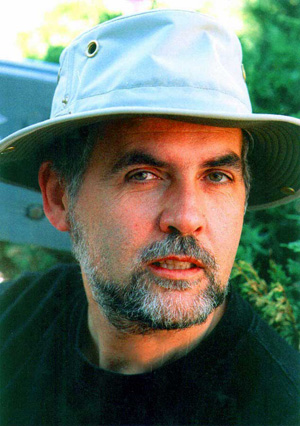

John Archibald

* * * * * * * *