Reviews

Fiction Review by Justin Pfefferle

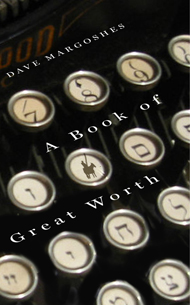

Dave Margoshes, A Book of Great Worth (Regina: Coteau, 2012). Paperbound, 250 pp., $18.95.

Great short stories are like great photographs: they command our attention with local details, but they also point us toward the world beyond the frame. Trafficking in the immediate and sometimes-overlooked, they renew our sense of ordinary, humdrum reality. Masters of short fiction and master photographers know that the minutia of everyday life can be of great worth. Little things may have tremendous significance, in themselves and as parts of a bigger picture.

The narrator of A Book of Great Worth, a collection of short fiction by Dave Margoshes, arranges stories like snapshots in a photo album. In the foreground of each picture stands Harry Morgenstern, a fictionalized version of the author’s actual father, Harry Margoshes, who passed away in 1975. The author’s fictional counterpart plays the role of dutiful son, paying homage to his father by recounting stories of Harry’s life as a journalist in 1920s and 1930s New York. Harry performs no great deeds, no acts of heroism or political intrigue. He’s neither a great philosopher, nor a great poet; he’s not a great lover, nor does he protect some awful, long-kept family secret. He has friends, a wife, children, and a job. He copes, or fails to cope, with the trivialities and minor eruptions of daily existence. There’s little to make his life especially noteworthy. Harry, like many of our fathers, is simply a man, a person who lived for a while and eventually died. For Margoshes and his narrator, the stories are priceless. To tell a story about a deceased loved one is to bring that person back to life, at least in the imagination. Each story balances imaginative elements and actual events. Margoshes employs a fictional double to give his “father” psychological interiority, layers of beliefs, desires, motivations, and anxieties that couldn’t have been available to the author in real life. “A Book of Great Worth,” the title story of the collection, concludes: “From the living room, he thought he heard the tinkling of piano keys, the first tentative notes of a Chopin concerto, but it was only the sound of an automobile passing on the street below, rising through the warm night air and the open window. His side ached, just beneath the strawberry stain by his heart, and he didn’t know if it was the incision, or something else.” Access to such mental conflict—was Harry feeling the pains of a recent appendectomy or the pangs of a beleaguered heart?—is the essence of fiction. “Dave” moves between omniscient and limited narration, now filling in impossible details, now coming up against a wall of unknowability. This kind of narrative dexterity calls attention to the stories as works of the imagination; it’s also what brings Harry to life. Margoshes uses fiction to reanimate his father; in doing this, he proves the real value of the make-believe.

A Book of Great Worth circulates multiple currencies. Monetary, sentimental, familial, ethical, and political values define characters’ relationships with one another. Harry gets touched for money by friends and relations in several stories. In “A False Moustache,” his friend Shmelke impregnates a woman, whom Harry must help because his friend is broke. “A Distant Relation” features the mysterious appearance of Rueben, a cousin from Montreal, who asks Harry for a loan of fifty dollars moments after introducing himself. In “Music by Rodgers, Lyrics by Hart,” a disagreement over money strains the friendship between the Morgensterns and the Cahans after Harry’s wife, Bertie, and Moishe Cahan win a thousand dollars in a contest. The ways that characters calculate value are always individual and relative, never universal or absolute. Even money matters differently to different people at different times. Harry enjoyed some level of prosperity during the Depression, so he can afford to be magnanimous in his row with the Cahans; as his wife put it, they “needed [the money] much more than we did.” Some things can’t be fixed with a price tag, because their value is personal, not common. In “Lettres d’amour,” Harry and Bertie exchange love letters while Harry works out of town. In a later story, the narrator recalls finding the letters, “bound with a blue velvet ribbon,” along with poems that his mother had penned in her spare time. The narrator admits that the poems aren’t very good. Like the collection of letters, they have little value as literary or historical documents. Yet he cherishes the poems, just as Bertie cherished her letters, because they tell stories of private devotion. His mother dedicated herself to her family, not her art. With good reason, her literary outpouring will never see the light of day. For “Dave,” however, their worth can’t be quantified. They express something that he alone can appreciate, in the same way that the letters speak only to Harry and Bertie.

Snapshots, such as those that appear in photo albums, are similarly priceless—but only to those for whom they have sentimental value. The picture-taker may, accidentally, capture some striking effect—a gleam in the subject’s eye, a beam of light filtered through venetian blinds—but snapshots rarely achieve the status of art. Such is the case with many of the stories in this collection. Margoshes is an accomplished professional, but “Dave” writes, at times, like an amateur. Clunky prose and inefficient sentences characterize a work of little aesthetic, but great personal, value. A Book of Great Worth may be a book of great worth only to those who knew and loved its central character. Those of us who did neither might approach this collection in the same way that we flip through the photo albums of strangers, on the lookout for charming details, not creative achievements.

—Justin Pfefferle