Reviews

Fiction Review by Shane Neilson

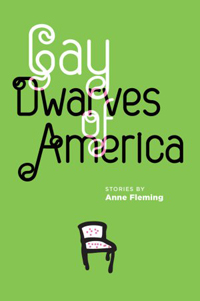

Anne Fleming, Gay Dwarves of America (Toronto: Pedlar, 2012). Paperbound, 208 pp., $21.

In the contemporary now, story is at risk of getting lost in a structural geek-out, but there is a frontier which will always be a frontier for all forms, be they novels, novellas, short stories, or microfiction. The frontier is form itself. A writer who innovates within a form with success is redrafting the idea of “perfection.” It isn’t enough to just write a short story anymore. Perhaps the short story has to be an ostentatious object before it can get respect from its more solemn cousin the novel, akin to “it’s not how big you are, it’s what you do with it.” The novel has size, but the short story must perform.

Anne Fleming’s first story in Gay Dwarves of America is a perfect short story of the 1.0 variety—a story with a clear narrative. “Unicycle Boys” is about a young woman who goes on a prom date with a boy she once knew quite well but with whom she fell out of touch, only to meet again by chance years later. The story is quirky but it is also savagely funny, a part satire/part love letter to the world of teenage girls that could only have been written by a writer in thrall to the motivations of her characters. The reversals within “Unicycle Boys” occur in a masterfully short space. The shy and genuine spirit of the male suitor is tenderly captured, and the dark pleasure people take in humiliating one another gives the story its power. Fleming varies her prose constantly, riffing in a list-like fashion within one paragraph and then talk-and-moving her mean girls. The element of silliness and fancy is always kept close. The female protagonist even indulges in some aphoristic formulations about her own life that temper her baser insinuations and make her as much a failure, when put in perspective, as the rest of the cast.

The first story serves as a proof: yes, Fleming can vary the tense so that the address can be both first-person present and past, the point of view revolves expertly, emotion is wrung out of the lives of children. But the second story, which also serves as the title of the collection, is where Fleming tries to move past convention. “Gay Dwarves of America” is an innovative story, meaning: the introduction is, on first reading, incomprehensible. One can’t know what is happening until several pages in. Characters crack wise without a reader understanding who they are. Action happens, mostly in the heads of these characters, without the action being completely explained. The story concerns two male university students who share an apartment and also host a hoax website about gay dwarves, the latter circumstance occurring as a result of randomness (the site had to be something). The students indulge in a morally contemptible email exchange with the mother of a gay dwarf. Oh, and one of the students spends time completing a preposterous urban planning assignment as a set piece that comprises the bulk of the opening scene’s obscurity.

What’s lost in all of this deliberate tricksiness, zaniness, and (hallelujah!) innovation? Story. Emotion. Two guys share an apartment. A homosexual undercurrent culminates in a “failed move.” The roommates don’t interact much except in terms of sarcasm. There isn’t much story or emotion, just relentlessly inventive quirkiness. Lots of fun is had being silly about urban planning and making jokes about gay dwarfdom, but the story about the two men is lost because the camera just wants to have fun and not stick to centre stage. The story ends as randomly as it began, with a possible ex-roommate sending the other ex-roommate a series of one-word postcards. The formal innovation on display is impressive but the analog technology of story is on the fritz.

But the point of innovation is to prove itself. My copy of GDOA is full of marginalia. I wish I had more space to individually crack open Fleming’s remaining stories that also display her preternatural voice, her tremendous prose energy, and her unique conceits. (Short story writers should consult this book as a manual of the form.) Most of all, I wish I could write more about Fleming’s inhabitation of character. There is a bite to these characters, the cringe-inducing presence they possess when making the wrong choice, or the first choice, their embarrassments and, best of all, their joy when they go for what they want and succeed. In other words, the technical elements of several of the remaining stories do not sacrifice what will always be required to make the short story “perfect”: emotion and moral development of character. For example, “Puke Diary” is a story that begins in the voice of a barfing cat but the story roams as far as marriage and birth within a nexus of family. It is a performance that must be read to be believed, its vulgar conceit becoming a magnificent portal into a range of existences.

The main criticism of the collection is that conceits make or break Fleming’s stories (success with vomitus, failure with a musical). A smaller concern involves the author’s greater skill with female main characters—her men aren’t as complex. Also, GDOA is adolescent in terms of the spectrum of lives it depicts (mostly children and young adults). No doubt Fleming will eventually turn her technique upon more-lived lives to amplify her stories’ power.

The perfect short story has to have a perfect image to remember it by. But every Fleming story has so many virtuoso notes, time will have to pass before I can forget enough of them to be left with just one. For this collection, perhaps the image of Swiss “Hildie,” the maker of cheese, cheering with a cowbell at hockey games can serve as the ur-image. Hildie’s a stroke of a character within an actual character, Heather, the female protagonist of the story, “Thorn-Blossoms.” Hildie is Heather’s alter-ego, a few short lines of genius within a larger container of genius, the perfect short story. Go look. I wish I could write more.

—Shane Neilson