Reviews

Fiction Review by Laurie D Graham

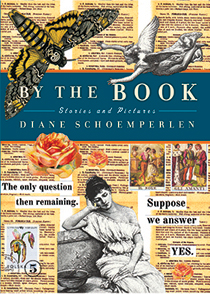

Diane Schoemperlen, By The Book: Stories and Pictures (Windsor: Biblioasis, 2014). Hardcover, 218 pp., $29.95.

There are no less than three Diane Schoemperlens. First, there’s the Schoemperlen  of the straightforward narrative: think “Hockey Night in Canada” or Our Lady of the Lost and Found. She often focuses on love, the lack of it, the failure of it, and the things people do in pursuit of even an unreasonable facsimile of it. Second, there’s the Schoemperlen who monkeys with form and perspective and what tropes might be possible in a piece of fiction: see “This Town” and “True and False” for examples. Third, and perhaps most distinctive, there’s the Schoemperlen of Double Exposure—her first book, published three decades ago by Coach House Books—of the Governor General’s Award-winning Forms of Devotion and, most recently, of By The Book, a series of “found narratives” that act as a sequel, of sorts, to Forms of Devotion. By The Book combines fragment and collage to form something…else. It’s tough to describe the seven pieces that make up this book, and even harder to articulate their precise effect. There are no story arcs, in the traditional sense, save for the first piece, which builds a more traditional, though off-kilter, fiction out of fragments from an Italian-English handbook from 1900. Absent as well are plot or character or setting or any of those bedrocks you expect from prose. Yet, in a way, what we’re reading are stories all the same. I think here of the idea attributed to Miles Davis or Claude Debussy or all of dub music: it’s the space between the notes that makes the music.

of the straightforward narrative: think “Hockey Night in Canada” or Our Lady of the Lost and Found. She often focuses on love, the lack of it, the failure of it, and the things people do in pursuit of even an unreasonable facsimile of it. Second, there’s the Schoemperlen who monkeys with form and perspective and what tropes might be possible in a piece of fiction: see “This Town” and “True and False” for examples. Third, and perhaps most distinctive, there’s the Schoemperlen of Double Exposure—her first book, published three decades ago by Coach House Books—of the Governor General’s Award-winning Forms of Devotion and, most recently, of By The Book, a series of “found narratives” that act as a sequel, of sorts, to Forms of Devotion. By The Book combines fragment and collage to form something…else. It’s tough to describe the seven pieces that make up this book, and even harder to articulate their precise effect. There are no story arcs, in the traditional sense, save for the first piece, which builds a more traditional, though off-kilter, fiction out of fragments from an Italian-English handbook from 1900. Absent as well are plot or character or setting or any of those bedrocks you expect from prose. Yet, in a way, what we’re reading are stories all the same. I think here of the idea attributed to Miles Davis or Claude Debussy or all of dub music: it’s the space between the notes that makes the music.

By The Book is at least partly engaged in speaking through its silences. Case in point: “History Becomes Authentic Or: The Question Of Things Happening,” which takes as its source The Cyclopedia of Classified Dates With An Exhaustive Index, a 115-year-old, 1500-page tome that claims to contain a chronological history of the globe. In her author’s note that begins the piece and names its source text, Schoemperlen explains how she “selected the events that interested [her] and rearranged them in new sections.” One such section is called “The Short Story Of A Large City”:

Rome is alarmed. Rome is terrified. Rome is sacked. Rome is recovered. Rome is smitten with pestilence. Rome is burned. Rome is rebuilt. Rome is taken. Rome is restored. Rome is embellished. Rome is besieged. Rome is pillaged. Rome is rebuilt on a grandscale. Rome is visited by a snowfall, the first in 240 years. Rome is supreme.

Then, on the opposite page, we have Schoemperlen’s collage of this “short story,” which further rearranges the rearranged text. The collages that appear at intervals throughout the book act as illustration, elaboration, and alternate, producing, along with the text, a conduit to a third, unnamable “thing” growing behind the words and images. The reader is ceaselessly active in By The Book; the reader makes as much narrative as the author. Notice the tight anaphora in the passage above. Notice how it cleaves to the general. Where else does your mind go when you read these words but to something specific? The way the text “works” on the reader becomes crucial to each story.

Schoemperlen has a knack for writing effective generalities, and in this book each uncontested, though manipulated, broad stroke illuminates gaping blind spots and failures in the speaker’s (and the reader’s) vision: “Paganism, merits discussed. Painter, Thomas, whipped. Paper, endless, invented by Robert. Paris, carries off Helen. Parsons, Lucy, anarchist, arrested. Pauline, captured. Peacemaker, explodes.” In “What Is A Hat? Where Is Constantinople? Who Was Sir Walter Raleigh? And Many Other Common Questions, Some With Answers, Some Without,” we hear the voice of a whole terrible dominion educating its young. We start to hear both a specific voice and a common voice simultaneously. Add to this the knowledge that the words are pulled from children’s readers and the “plot” grows that much more sinister, more hideous:

Q. Is not the extent of India very great?

A. Yes: it is about fifteen times the size of Great Britain, and contains a population estimated at 200 millions.

Q. Are we not responsible as a nation for the well-being of this immense multitude?

A. Yes; God has made England the most powerful of all nations, and we ought, therefore, to govern with mercy and justice.

Q. Why?

A. Because if we do so, He will continue to bless and prosper us.

I have only just hinted at all the things By The Book could be about. Its scope is huge and impossible to grasp fully. One sees a similar hugeness in the work of artist Ai Weiwei: an endless, almost deforming multiplication of items, of names, of “things.” One’s capacity is tested and becomes paramount and ultimately falters. As Schoemperlen states in her introduction to the book, “The creative possibilities offered by this intersection of the written word and the visual images are unlimited, the juxtaposition of these two elements producing frequently startling explorations of connection and disconnection, resonance and dissonance.” For the reader of By The Book, the creative possibilities might involve asking how we handle the presence of so much information, how we have ever handled it, and what the gaps might be able to tell us.

—Laurie D Graham