Reviews

Fiction Review by Lori Garrison

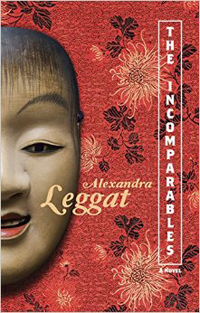

Alexandra Leggat, The Incomparables (Vancouver: Anvil, 2014). Paperbound, 314 pp., $20.

The Johnny Cash classic “One Piece at a Time” is the ballad of a Detroit auto worker who builds himself a Cadillac by smuggling it out part by part in his lunch box. When he finally puts it together he discovers that, as the pieces are all from different years, nothing quite fits together the way it should, leaving him with a “ '55 '56 '57 '58... (etc) automobile.” This patchwork craftsmanship nicely describes Alexandra Leggat's The Incomparables, an awkward jalopy of a book which is nonetheless charming in its eccentricities.

The Johnny Cash classic “One Piece at a Time” is the ballad of a Detroit auto worker who builds himself a Cadillac by smuggling it out part by part in his lunch box. When he finally puts it together he discovers that, as the pieces are all from different years, nothing quite fits together the way it should, leaving him with a “ '55 '56 '57 '58... (etc) automobile.” This patchwork craftsmanship nicely describes Alexandra Leggat's The Incomparables, an awkward jalopy of a book which is nonetheless charming in its eccentricities.

The plot revolves around Lydia, a thirty-something seamstress who designs costumes for a theatre company until she is fired for her unprofessional conduct following the discovery that her thespian husband, Charlie, is cheating on her with the leading lady of the production. She returns to her small-town childhood home to live with her mother for a month while she recuperates from the emotional fallout of these two events, but finds only more problems as her mother deals with the recent death of Lydia's father and her own failing health. Unfortunately, the plot becomes totally unbelievable upon Lydia's introduction to the mysterious “Counselors,” who have come to town to run the cult-like alternative-education “Dragon Staff Certificate Program,” to which the residents of the town have willingly surrendered their children for purposes never fully explained. The Counselors—Kaito, Pipit, and their leader, Raiden—are supposedly Japanese, and espouse a Zen-like philosophy whereby one attempts to escape “the claws and fangs of the dharma cave,” though, according to Pipit, “not everyone can reach enlightenment, and very few women do.” This flowery, neo-Eastern mysticism cloaks the novel in a pall of colonial-style orientalism; everything the Counselors do is imminently “other,” a step away from the mundane, small-town Westerners.

Plots and subplots abound, but none ever fully or satisfyingly develop. Jane, Lydia's childhood friend, appears partway into the novel without any prior introduction to proclaim a grudge against Lydia for going to live in the city to pursue her career while Jane remained behind as a teenage mother to raise her now nearly-grown son. Neither son nor mother makes an appreciable impact on the story and feel thrown in at the last minute. Rosa, Lydia's best friend, seems to know more than she lets on about Charlie's affair, but what she has withheld, or why, is never resolved. Junko—an over-the-top character who lives as the ward of Raiden and his crew, spouts obtuse koans about “The Mirror Cave,” and refuses to go out without a Noh-style mask covering her face—builds the backbone of the main plot, which involves her mysterious knowledge of Lydia's late father and her impending “marriage” to Raiden in a mysterious “ceremony,” the purpose of which is clearly beyond matrimony. With so much going on—and so much of it utterly nonsensical—the novel becomes a garbled mix of Lydia's mid-life anxieties about love, careers, baby-making, and obnoxious existentialism.

Even if the narrative were better structured, it wouldn't make up for the novel's primary failing, namely that it is populated by characters who are utterly two-dimensional, appearing more as caricatures to emphasize philosophical points than as actual people you might meet. Lydia suffers from this most acutely, as she is not only dull and difficult to imagine but eminently unlikeable, selfish, childlike, and melodramatic; readers may have a hard time connecting with her, and thus have difficulty caring about what happens in the novel at all. Another problem is with the dialogue, which feels forced and artificial. Total strangers have deep and meaningful conversations with each other immediately, argue without any apparent conflict and wax romantic about life in ways and at moments that seem totally manufactured by the author. The scene where Lydia meets Raiden for the first time in a pub and orders a pint of Blue, only to have Raiden remark seriously, “Yes, blue... the colour of hopelessness, the colour of melancholy,” is typical of the novel's interactions and dialogue, which are often not only unbelievable, but laughable.

Despite this, readers may find themselves genuinely intrigued, and Leggat skillfully withholds then deals out information in thin layers so that we are consistently curious. However, things fit together far too neatly, which leads the novel to have a packaged feel—Lydia's last name is the dramatically-loaded “Templar,” her husband plays Romeo and falls for Juliet, who is played by the actress Imogen, which is the name of a princess inCymbeline, which is also the name of Lydia's more-successful older sister's restaurant. Readers may find themselves frustrated by the increasingly convoluted plot machinations and heavy-handed symbolism that goes nowhere, or feel cheated by the ending, which fails to tie the disparate ends of the work together in a meaningful way. Readers who know Leggat through her masterwork of succinct, distilled short fiction, Animal, may find themselves sorely disappointed.

—Lori Garrison