Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Carleigh Baker

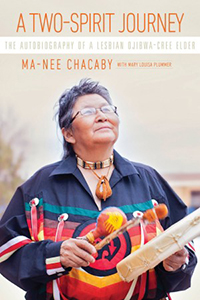

Ma-Nee Chacaby, A Two-Spirit Journey: The Autobiography of a Lesbian Ojibwa-Cree Elder (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 2016). Paperbound, 244 pp., $24.95.

A Two-Spirit Journey by Ma-Nee Chacaby is a story of resilience and hope. It’s also groundbreaking, as co-author Mary Louisa Plummer points out: “[Chacaby] has lived through important historical transitions and few records of those times are written from the perspective of someone like her, that is, a poor, recovering alcoholic, visually impaired, and lesbian Indigenous woman.” While Chacaby’s voice is undeniably among the under-represented, the greater theme here—endurance of spirit in the face of violence, prejudice, and poverty—holds lessons for all readers. Also, she’s got some keen storytelling chops. Chacaby’s precise language and unflinching honesty make this book an absolute triumph.

A Two-Spirit Journey by Ma-Nee Chacaby is a story of resilience and hope. It’s also groundbreaking, as co-author Mary Louisa Plummer points out: “[Chacaby] has lived through important historical transitions and few records of those times are written from the perspective of someone like her, that is, a poor, recovering alcoholic, visually impaired, and lesbian Indigenous woman.” While Chacaby’s voice is undeniably among the under-represented, the greater theme here—endurance of spirit in the face of violence, prejudice, and poverty—holds lessons for all readers. Also, she’s got some keen storytelling chops. Chacaby’s precise language and unflinching honesty make this book an absolute triumph.

Chacaby was raised by her Cree grandmother, in a remote town in northwestern Ontario. Ombabika, an Ojibwa-Cree community, had a Protestant church and a school with white teachers who spoke English, despite a sizeable majority of Ojibwa-speaking Anishinaabeg. Chacaby dropped out at a young age, and did not attend a residential school. As a result, she was a late adopter of English, though she spoke both Cree and Ojibwa. She recalls watching Sesame Street with her young children to learn the alphabet, practising writing the letters in a hardback journal. Despite this delayed introduction, in later years she worked as a translator and interpreter for the government, and a drug and alcohol counsellor.

A Two-Spirit Journey contains a wealth of cultural and social insight. The perceived value of women—specifically Indigenous women—in the 1970s and 80s is brought into sharp focus. Chacaby tells this story about visiting the construction site where her boyfriend worked: “… a worker there came up to me and said, ‘Hey, you’re young and I bet you run fast. I’ll pay you a lot of money if you take this bag, run up that hill, cross over those rapids, and leave the bag right there. Then run back as fast as you can.’ I agreed, so he lit the string hanging out of the bag, and I did just as he instructed. Of course, he had me setting off dynamite, but I didn’t really understand how explosives worked at the time. In the end, though, I realize they were using me to do a very dangerous task.”

Stories like this are almost shrugged off by Chacaby, but it’s not hyperbolic to say that for many years the presence of violence and death was a reality. Sometimes, it overwhelmed her. After losing a child to sudden infant death syndrome, she descended into an alcoholic binge. She later surfaced only to find that her other two kids had been seized by Children’s Aid. After entering Alcoholics Anonymous and getting sober, she was able to successfully get them back. Then there was no turning back for Chacaby, who, along with her second husband, went on to foster many children. Chacaby’s second marriage collapsed several years before she came out as a lesbian in 1988.There is a common misconception that two-spirited people maintained the community acceptance they enjoyed in many pre-contact Indigenous cultures. In fact, colonialism’s impact included a heavy dose of shame, enforced by missionaries. Still, Chacaby allowed herself to be interviewed at a gay and lesbian event in Thunder Bay. After the interview was aired on TV, she was assaulted several times. “I was walking down a sidewalk when out of nowhere [a female relative] started hitting me and calling me names. …She was with four Anishinaabe men and women who also beat and kicked me. The whole time, she shouted at me, saying I was ruining life for other Native people by being a lesbian.” Fortunately, a taxi driver intervened, and drove the badly bruised Chacaby to a women’s centre.

Not long after coming out, Chacaby met Leah, her first love. She describes the experience of coming to terms with her sexuality: “…there were days I saw myself as a piece of a jigsaw puzzle that, until then, had been forced into the wrong spaces, even into the wrong puzzle. But at last I had found the right puzzle, and I fit very well.” Not surprisingly, intimate relationships were still a challenge, after many years of trauma and loss. However, it seems that the loving relationships she experienced during this time helped Chacaby to move into the period of intense healing that characterized her later years. Now, as an Elder, Chacaby leads healing ceremonies. She says: “…sometimes we face great challenges, but that is all the more reason to cherish the pleasure, humour, and joy in our lives and the world around us.”

Ma-Nee Chacaby’s story is important, and honouring her voice is equally important. A word here on the co-authorship of A Two-Spirit Journey. Because Chacaby has severely limited vision, she asked Mary Louisa Plummer, a longtime friend, to handle the transcription and writing. Over Skype, Chacaby dictated the details of her life in rough chronological order. Plummer then transcribed and assembled the material into a manuscript and read it back to Chacaby over Skype, and Chacaby requested edits, deletions, and additions. Further revisions were made after a peer review process. Plummer, who is not Indigenous, discusses the politics of cross-cultural co-authorship in the afterword. Readers who aren’t familiar with this debate might want to take a look before digging into the book. As our understanding of the colonial impact on Indigenous representation broadens, these discussions present opportunities for non-Indigenous readers to engage more deeply with the text.

—Carleigh Baker