Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Marguerite MacKenzie

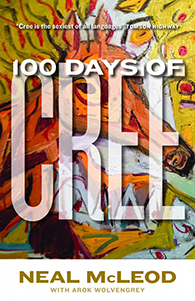

Neal McLeod, 100 Days of Cree (Regina: University of Regina, 2016). Paperbound, 325 pp., $24.95.

This book is all the things that most language learning materials are not—fun, unpretentious, readable, stimulating. It is a book to dip into and follow your interests, with serendipitous results. The linguistic oversight by Arok Wolvengrey provides consistency that does justice to the words, while Neal McLeod's text makes the daunting task of learning Cree seem attainable and entertaining. Ten words a day for 100 days should not be too far beyond a dedicated language learner; as a bonus the words come with history and culture unfamiliar to most Canadians. Reflecting a highly personal engagement between the author, his people, and their language, this book is full of humour, with funny words and self-deprecating stories. Few Canadians have the opportunity to find out just how much fun it is to hang out with Indigenous people, who are masters of imitation and jokes. When Cree speakers get together, be it to make up terminology or even to record verb conjugations, the occasion is regularly punctuated with gales of laughter.

This book is all the things that most language learning materials are not—fun, unpretentious, readable, stimulating. It is a book to dip into and follow your interests, with serendipitous results. The linguistic oversight by Arok Wolvengrey provides consistency that does justice to the words, while Neal McLeod's text makes the daunting task of learning Cree seem attainable and entertaining. Ten words a day for 100 days should not be too far beyond a dedicated language learner; as a bonus the words come with history and culture unfamiliar to most Canadians. Reflecting a highly personal engagement between the author, his people, and their language, this book is full of humour, with funny words and self-deprecating stories. Few Canadians have the opportunity to find out just how much fun it is to hang out with Indigenous people, who are masters of imitation and jokes. When Cree speakers get together, be it to make up terminology or even to record verb conjugations, the occasion is regularly punctuated with gales of laughter.

The heart of the Cree language is the creation of words, old and new, and McLeod shows us that one does not have to be an expert speaker to engage in this fun activity. On the modern side, he gives us Cree terms for poker, Tim Hortons, Facebook, Johnny Cash and Leonard Cohen songs, computers, and the rodeo. On the traditional side are words and comments about nature, the land, horses, warfare, and many practical terms for everyday items. The sections on being Cree help us to understand the people, their character, feelings, and social world. The funny Cree expressions include my own favourites, fart words, as in the eastern communities where I work, Fart Man frequently speaks and his utterances are interpreted by others in the tent.

Cree is a grammatically complex language, built on principles that are quite different from those of English or French. While it has nouns, verbs, and function words (prepositions, adverbs, numbers, demonstratives, etc.), the proportions are significantly different: at least eighty per cent of words are verbs and fifteen per cent nouns. Words are often long and usually translated with an English sentence. Nouns for new concepts are often built on verbs, which have at least as many conjugations as does French, each conjugation with a variety of prefixes and suffixes. Grammatical concepts of preverbs locative, obviative, animate and inanimate gender are slipped in painlessly. We learn to recognize the comprehensive sense of a word aided by the author’s separation of the smaller pieces of meaning (morphemes) with explanations of these. Each is equivalent to a single concept, dropped throughout the book at a pace that does not feel at all like the tedious study of grammar. By Day 100, a reader will have accumulated a fair bit of such knowledge.

McLeod links literary theory to the tradition of orality from which the old stories come. In introducing us to Cree literature through the Plains Cree texts collected over 100 years ago, he raises the important issue of the need for new and accurate translations of historical accounts. Who knows how much of what we think we know about Indigenous culture is based on approximate translations that do not reflect the nuances and precision of the complex vocabulary? When oral information is collected for scientific, legal, historical, or other purposes, and interpreted into a European language, there is little time for the speaker or the audience to reflect on the nuances added by every Cree morpheme, but there is great scope for misunderstanding.

The record of a long historical contact with Europeans is preserved through English and French vocabulary incorporated into the language. In the case of French words, the article “la”or “le” often came along for the ride, as in napwen from la poêle “frying pan.” In Innu, first recorded by French missionaries in the 1600s, one meets napuenassiku, with the Innu version of Cree aschihk “kettle, pot” attached. Surrounding an English word with Cree prefixes and suffixes as in niwallim “my (Facebook) wall” is a sign of a strong and confident language that uses all strategies to increase vocabulary as needed.

Although the focus is on the Plains dialect of Cree, the entire language extends to the east coast of Canada, changing its name and the spelling and pronunciation of words, much as does English as it spread from Great Britain to North America, Australia, New Zealand, and further. The most easterly speakers of Innu in Quebec-Labrador, of Naskapi, East Cree and Atikamekw in northern Quebec, of Moose, Mushkegowuk (Swampy) and Woods Cree dialects in Ontario and Manitoba recognize with little difficulty the word for “you” (singular), whether pronounced or spelled as kîya, kîna, kîtha, kîla, kîr, chîy, tshil, tshin. Likewise, kipaha, meaning “close it” can occur as chipaha or tshipai as sound changes are regular and predictable, much like the Cockney pronunciation of “mother” as “muvver.”

Nevertheless, the proliferation of dialects, and the fragmentation of the national speech community by provincial, religious, and second-language boundaries, has put the future of Cree in jeopardy. Across the country, children are hearing less Cree at home. McLeod's book may well contribute to the revitalization of the Cree language in a way more academic efforts may not. On a positive note, there are now many websites where you can hear and see the words and stories of Canadian Indigenous languages, through dictionaries with sound files, place-name maps, narration of traditional tales, and more. I urge you to explore them all.

—Marguerite MacKenzie